About 56 years before his exit from the theatre of life, Irfan Husain enacted a dramatic death on the stage in 1964. He played a co-conspirator led by Brutus in the assassination of Julius Caesar, so evocatively narrated by Shakespeare in Julius Caesar. I was privileged to be Irfan’s friend and a co-conspirator in the same play while our own pact of friendship endured through the fact and fiction of life for the next five and a half decades.

One of Dawn’s most distinguished columnists began his higher education at the University of Karachi in 1963. As fellow students, we quickly discovered a shared sense of humour and a quest to explore new vistas — one of these being to help establish the Students’ Theatre Guild and stage plays in English.

When the vice chancellor and venerable scholar Dr I.H. Qureshi, who was conversative by bent, politely but firmly declined to permit the staging of plays on campus, we decided to use the stages at the Karachi Grammar School and the Theosophical Hall.

We were part of an extraordinary group of young women and men, at slightly different stages of becoming full-blown adults, though some of us had already crossed that milestone. From different departments of the arts faculty and other faculties, including a couple of lecturers, we brought to our adventures an infectious blend of enthusiasm, talent, capacity for hilarious lapses and a sense of sheer fun.

Our colleagues included junior lecturer Javid Ali Khan, Qasim Ishaque, Jamal Pasha, Shahinda Dhanani, Lubna Effendi, Anwar Maqsood, Ismat Parekh, Rehana Ali Khan, Roshni Irani, Shahid Nazir Ahmed, Najma Hussain, Ameena Saiyid, Mujahid Hussain, Rupina Modi, Rhoda Vania, Rehana Sharif, Akbar Agha, Masood Haider, Akbar Fasih, Zeenut Anis, Akbar Noman, Attaur Rahman (from the Science Faculty), Roohi Zakaullah, Mubarak Ali Khan, Nuzhat Suleri and, for one play, Shirley Haider and Shahnaz Wazir Ali.

Irfan Husain was, in the finest sense of the term, a true liberal. He transcended differences of nations, regions and cultures. But he also enjoyed camaraderie and life

In three years, we presented three plays. After the lapse-filled debut with Julius Caesar, we produced two rollicking American comedies by Moss Hart and George Kaufman: You Can’t Take It With You (which we also took to Lahore) and The Man Who Came To Dinner. Though he was not at the university, Ali Khan (not Javid) was our quixotic, capable director. Post-university, we also presented The Promise, a three-character Russian play, in which Hasan Jawad joined us.

Irfan’s home was an unusual haven. There was casual, warm hospitality from his gracious mother, Mrs Hamida Husain. She was often seated on a takht (wooden divan) with a paandaan (ornate container to store betel leaf and its ingredients), was as inexhaustible as her kitchen, which fed the steady stream of her son’s friends with delicious snacks and curries. In later years, she became an accomplished author.

Irfan’s father, the eminent scholar Dr Akhtar Husain Raipuri was reclusive but, whenever seen, gentle and tolerant of intruders. Irfan’s eldest brother Salman was a real darvesh (sufi type), almost always burrowed into a book, deceptively quiet but with strong convictions. His younger brother Navaid Husain became a successful architect. He was one of the pioneers of Shehri, which led the campaign to protect Karachi from the ravages of corrupt building practices. Navaid survived a vicious, almost-lethal attack by a construction mafia. His other younger brother, Shahid, grew up to become a fine professional in the US.

From the start of his induction into the government’s railways service, Irfan declined to be shaped mainly by his job — even though the work we render does help mould character and personality. He was able to maintain a detachment and perspective about the state and the government-of-the-day, seen from the viewpoint of a fair-minded citizen.

By writing under pseudonyms because of the constraints of being a government official, initially using his first wife Ferida Sher’s name, or later his son Shakir’s name or retrieving the almost mythical name of Mazdak, Irfan concealed his name only for a benign purpose — to candidly express and share convictions on issues that required urgent reform, advocacy and consensus-building.

In his hundreds of columns over thousands of days and in his book, Fatal Fault Lines: Pakistan, Islam and the West (2012) Irfan wrote with candour, anger, pungency, fluency and caustic humour. The range of his interests included constitutions and cuisine, politics and power, religion and extremism, and individuals and institutions.

When he prematurely retired from government and cast aside the cloak of anonymity, he moved effortlessly to boldly assert his actual identity. Perhaps this was because Irfan was, in the finest sense of the term, a true liberal. Respectful of diversity. Particularly concerned about the vulnerability of religious minorities in a pre-dominantly Muslim population. Transcending differences of nations, regions, cultures to become a real humanist and a global citizen.

He loved to travel and to explore new places — and nuances. From work in the relatively prosaic sectors of audit and accounts, to the pressures of serving as information minister in the embassy of Pakistan in Washington DC, Irfan adjusted to new situations and challenges with under-stated confidence.

In his third wife, British writer Charlotte Breese, Irfan gained an invaluable companion. She gave him immense care and affection. Be it at their seaside home in Sri Lanka or in England — to both of which my wife Shabnam and I were always invited but, alas, were never able to stay with them in Sri Lanka — she enabled Irfan to continue his writing. Most importantly in the last two years of his life, when he battled a rare form of cancer, Charlotte remained his ever-present source of comfort and support.

I occasionally noticed that Irfan was uncomfortable with outward expressions of affection. But this was only a disguise for a sensitive human being. His nonchalance could sometimes be gruff and short, but never nasty.

In a parenting role that was unavoidably affected by three consecutive marriages, the bond he formed with son Shakir is like a role model for an ideal father-son relationship. One of the main reasons why they became friends and quasi-equals, was Irfan’s ready willingness to accept his progeny’s individuality, to desist from imposing patriarchal dominance that otherwise distorts a child’s development. In his own right, Shakir has become a thoughtful, outspoken analyst on important issues. With Charlotte and Javid, Shakir was at Irfan’s bedside in his final days.

Though we chose different professional paths, many aspects bound us together, such as the trials and tribulations of Karachi and Pakistan, the pleasure of many mutual friends, the delights of reading, the challenges of writing and the joys of travel. Our meetings were both sporadic and regular but always amiable and enjoyable despite rare dissents on my part about some of his views.

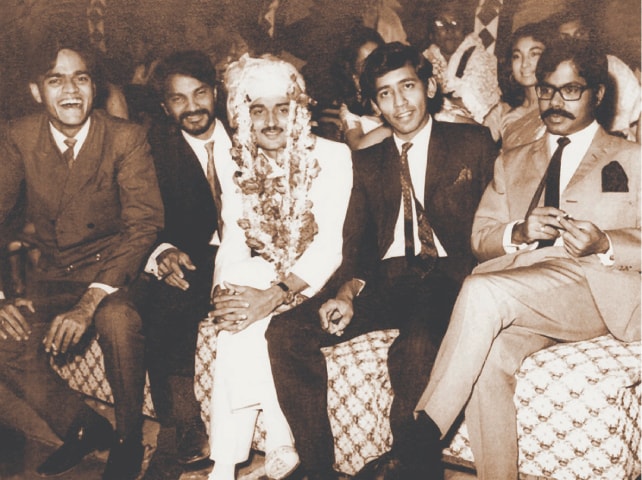

With Anwar Maqsood as a friend from our university days, Irfan relished Anwar’s irascible humour and wit. Memorably, both of us, and Javid Ali Khan, were present at Anwar’s wedding with Imrana in December 1969. Almost 50 years later, the four of us re-united in 2019 at Anwar Maqsood’s home, with Syed Jawaid Iqbal also present for a marvellous evening of reminiscences — little knowing that this would be our last time together.

Farewell co-conspirator and greatly missed friend, until we meet again, for our next play together.

The writer is an author, former senator and federal minister. He can be reached at www.javedjabbar.net

Published in Dawn, EOS, January 10th, 2021