SALUTE the Hazaras, one of the most gentle, peaceful and civilised communities in Pakistan. It was unfair to oblige them to supplicate for the prime minister’s attention — something they were entitled to receive without asking. The brutal and most horrible killing of 11 miners was a national catastrophe that should have brought to the scene the highest responsible authority in the land without anybody formally inviting it. What actually happened did not raise the government’s credit for its ability to respond to a national disaster and to honour its obligation to commiserate with its citizens over a terrible tragedy.

Who are the Hazaras and what have they done?

The Hazaras migrated to Balochistan over a long period in the 19th century and they were made to wait for decades before they were accepted as citizens in the land they had settled in. Their first vocation in Balochistan was to serve in the British Indian army and this enabled them to offer army chief Gen Muhammad Musa.

But as the Hazaras were neither sardars nor big landlords they didn’t have opportunities to oppress tenants at will. They chose to provide educated cadres to facilitate the management of the province’s affairs. There was a time they provided 70 per cent of the provincial government’s secretarial staff (now down to 20 or even less).

However, the Hazaras were able to rise to eminence in business and industry. They acquired ownership of mines and opened large departmental stores. They also won jobs in educational services and in banking and trade sectors.

A most striking feature of the Hazaras is their degree of tolerance for other communities.

The situation started becoming adverse for the Hazaras with the rise of religiosity in Balochistan. The previously empty marble mosques started attracting sizeable congregations. The arrival of religiously inspired militants from Punjab, the use of Balochistan as a launching pad for militants operating in Afghanistan, and finally the establishment of Taliban headquarters in Quetta made the environment unfriendly and eventually hostile to the Hazaras.

The fate of the Hazaras also began to be affected by developments in Afghanistan. When the Hazaras in Afghanistan joined the government there, the Hazaras in Pakistan were punished by the militants. Worse, the Hazaras found evidence to support their suspicion that their tormentors enjoyed the support of powerful sections in the government, even if the whole government was not a party to their suppression. These suspicions were grounded in the officials’ blatant indifference to their complaints and the persistent failure to proceed against the Hazaras’ persecutors. When action was at last taken against a couple of persons, they were allowed to escape from prison.

The Taliban campaign in Afghanistan also generated an anti-Shia wave in Balochistan and the Hazaras became victims of systematic attacks. In numerous incidents they were pulled out of public transport vehicles, subjected to identify checks and killed if their Hazara identity was established. For a long time, they were unable to put up any resistance but eventually they learned to reply to violence in the same coin, though on a small scale.

What completely disheartened the Hazaras was the fact that running normal business became more and more hazardous. They could not operate their mines and maintaining efficiency at their departmental stores became impossible. Many of them chose to abandon their fairly good jobs and went abroad in search of secure employment or business opportunities. One of their favourite destinations was Australia, and reports started to pour in of loss of life during attempts to travel from Thailand to Australia in rickety boats that often failed to reach their destination. But those who reached Australia made a good impression on their hosts. Australian authorities especially admired the industriousness of the Hazara womenfolk and their readiness to manage shops. In short, the discipline of diligence and honest dealings enabled the Hazaras to overcome the biases all communities have against immigrants of different racial stock and different habits.

The problem the Hazara workers face in an environment that has been made hostile to them by militants belonging to a different sect is that their identity is exposed by their facial features and national identity cards are checked only for ensuring that no non-Shia gets killed.

Despite all the hazards, the Hazaras have continued their educational mission. They run schools and colleges that are open to children belonging to all religious denominations and have been trying to establish a university for some years. They try to ensure that girls have as easy an access to educational facilities as boys and gender disparity in education is lower among them than in most other communities in Pakistan. Police records will confirm that although crime by Hazaras is not unknown they lag far behind other communities in making a living by crime, including common aberrations such as extortion and blackmail.

Anyone who has had contact with the Hazaras over a reasonable period will not fail to confirm that despite all the hazards they face they retain a healthy outlook on life and are full of optimism that they will survive whatever hardships are in store for them. A most striking feature of the Hazaras is their degree of tolerance for people belonging to other communities and denominations, which other communities in the country would do well to emulate.

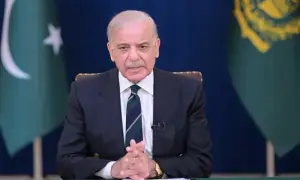

The Hazaras’ desire to gain the attention of the highest in the land has a history of unredeemed pledges made to them. It is true, as the information minister thoughtlessly keeps reminding the Hazaras, that misfortune has not befallen them for the first time, but it is also true that remedial measures promised to the Hazaras have not materialised. The prime minister did the Hazaras no favour by flying to Quetta after dictating terms. In any responsible dispensation, the head of government would have commiserated with the disaster victims without being invited. Kindness hedged with conditions has little value. Incidentally, the episode marked the formulation of what may be accepted as an Imran Khan doctrine according to which public demands cannot be accepted because then the dacoits will come up with their demands. Wonderful.

The nation has reason to be grateful to the Hazaras for setting models of forbearance in the face of calamity.

Published in Dawn, January 14th, 2021