THE morning Super Highway drive to Bahria Town is mostly uneventful, except for the piping hot potato samosas we have been nibbling on. Bahria Town, too, seems to have come into view too soon, probably due to the city having stretched so much in that direction that one doesn’t realise the distance travelled. We are not going in the main ‘shark jaw’ gates. We are making a detour via Kathore City. The people of Haji Ali Mohammad Goth, Dad Mohammad Gunder Goth and Ali Dad Gabol Goth have sent word out. They want to share something.

It is a well-known fact by now that the area where Bahria Town and several other such projects are coming up had many ancestral villages or goths. There are even native settlements there that are over 100 years old.

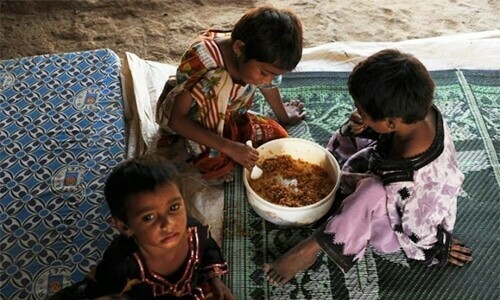

You spot a couple of straw huts surrounded by a three-side Bahria Town wall. Saima and her children have only recently moved here after being uprooted from another area where heavy construction work allegedly forced them out. “Now they are building a wall here, too. Whatever of our belongings comes in the way of their construction work they throw away,” the young mother reports.

Even the dead have not been spared. Entering Bahria Town from the back, you can see Ali Dad Gabol Goth’s ancestral graveyard. Across from it you see rows of neat-looking town houses, which are still unoccupied in Bahria Phase-III. They look like nice, cosy dwellings with open front areas. But then a gap between a row of town houses grabs your attention. What at first looks like a vacant plot covered by wild plantation, including a lot of thorny keekar, has something far worse than the thorns sticking out. There is a reason for the weeds to be allowed to grow wildly. They are there to hide old graves.

“All these houses, the sidewalks, roads … have been built over our ancestral graveyard,” says a local. Suddenly you realise that you are standing on the graveyard that you thought was across from you. More houses will soon come up over that side of the graveyard, too.

The funk of forty thousand years

And grisly ghouls from every tomb

Are closing in to seal your doom…

In his famous music album and accompanying scary video ‘Thriller’, did the late Michael Jackson foresee Bahria Town?

Suddenly you don’t know where to stand. You can’t breathe. Those samosas in your stomach, too, want to come up for air. What to do? Throw up? But not here, not in the middle of a graveyard!

According to Abira Ashfaq, a human rights lawyer, “Where does this Bahria Town land begin from and where does it end? So far some 45 such villages have been affected like this while three have been completely flattened. Ali Dad Gabol Goth has slabs dating back to Buddha times. Without any surveys, without any mapping, without taking the local people on board, state organisations and institutions such as the Board of Revenue, the Heritage Department, the Department of Antiquities, the Sindh Environmental Protection Agency, etc., all have allegedly sided with Malik Riaz and his Bahria Town.”

“We were happy the way we were,” says Amanullah Gabol. “But we were shown dreams of green pastures. Friends said there will be progress as they allow construction of roads, that there will be job opportunities. I told them not be attracted to glamour. And then there were roads here, there was housing here, but not for us. Those they were for are fast turning us into a minority. We are being harassed, we are being attacked, and we are being driven from this land of our ancestors.”

The locals shared last year’s incident of alleged land grabbing in Kathore and Gadap where they said Bahria Town was installing gates at places that have remained open pathways since British times. “I was not allowed to enter through the newly installed gates. When I tried forcing my way in, the guards there damaged my car and broke its windows before confiscating it,” said the aged Abdul Qadir.

“When our youth heard about this they protested and when things there became too heated, they broke the barriers. In their efforts to stop them, the Bahria Town guards even ran over one of them, Umeed Ali, who had to be rushed to hospital,” he claimed.

Intervention from Gadap Town SHO on the matter later resulted in reopening the pathway. “It is open now, but God knows for how long,” the old man wondered aloud.

He along with other locals praised their youth for having held their ground as bulldozing the goths means destruction of their orchards, agriculture land, poultry farms, canals, places of worship and hence their homes. The aim of such development only seems to drive them all away and remove any signs of existence so that the area around Kathore and Gadap seem like just barren wasteland. The stubborn among them who are refusing to move are finding themselves being confined and enclosed by Bahria Town walls and gates.

Published in Dawn, January 18th, 2021