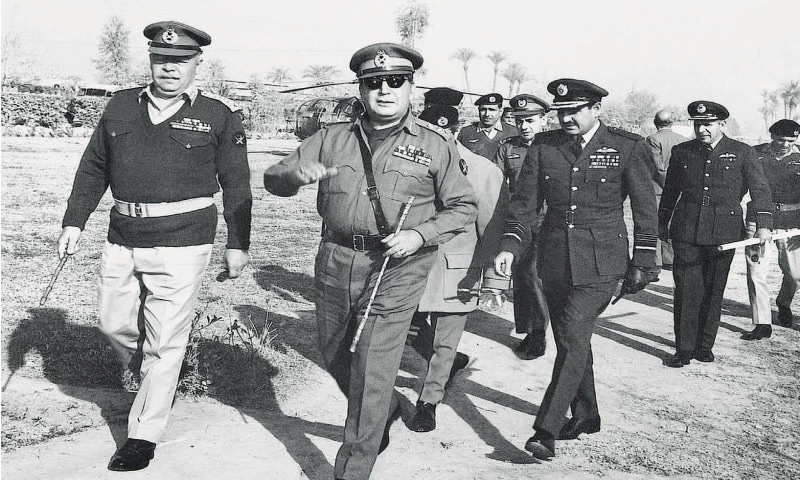

The man who comprehensively lost a war against India — and thereby lost half his country — Gen Agha Mohammad Yahya Khan deserves a full and accurate telling of his story and the story of how the Pakistan Army dutifully followed him into the abyss.

This slim volume — General Agha Mohammad Yahya Khan: The Rise and Fall of a Soldier 1947-1971 by Brig (Retd) A.R. Siddiqi — is not that book, especially since the author was responsible for Gen Yahya’s image-building during the critical waning period of his rule.

It brings to mind the title of the classic autobiography of Gen Sir Francis Tuker, the last British commander in Eastern India, who presided over the end of the British “watch and ward” function in the colony before its independence in 1947. While Memory Serves was Gen Tuker’s title. Brig Siddiqi, a journalist inducted by direct selection into the public relations branch of the military, and author of two previous and most useful books on the military, ends his new book with the coda “Reproduced as best as memory serves.”

Gen Tuker relied heavily on detailed contemporaneous diaries and notes; Brig Siddiqi’s book is an amalgam of anecdote and war stories without the sourcing and overarching contextual analysis that would peel back the layers of the onion that is the Pakistani military, and its fraught relationship with the country’s politics. It also appears to rely on segments of the author’s more useful and less hagiographic The Military in Pakistan: Image and Reality. The result is a gap-toothed volume that provides some interesting glimpses, but leaves you wanting for more. Brig Siddiqi needed a heavy dose of fact-checking and detail on Gen Yahya and the events that brought him to the pinnacle of power and his fall from grace.

Gen Yahya belonged to the generation of the British Indian Army that acquired the habits and accent of the British. But, unlike some of his colleagues in both independent Pakistan and India, he was not a reader or deep thinker. Rather, he saw himself as a man of action. Luckily for him, he became a favourite of Gen Ayub Khan — the first Pakistani army chief — and was carried along in the wake of that relationship into key positions at different stages of his rapid rise in independent Pakistan.

Brig Siddiqi refers to his role in the early building of the military relationship with the United States, but fails to note that Gen Yahya, as deputy chief of general staff, was in the first key meetings that then defence secretary Iskander Mirza called to prepare for the meetings with the US military aid review team under Brig Harry Meyers.

Gen Yahya Khan was at the helm of state and the army when Pakistan was torn asunder in 1971. Both he and the armed forces deserve a more full and accurate telling of their stories

Gen Yahya was reportedly also involved in helping Gen Ayub write the plan for the reorganisation of the Pakistan Army. He was also in that small, supporting cast that descended on Karachi when Lt Gen Wajid Ali Khan Burki and others were sent on the dangerous mission to Karachi to inform Mirza that he was no longer needed as president.

Gen Ayub chose to repair to the north at that juncture. Brig Siddiqi notes that, when Gen Ayub decided to relocate the capital from Karachi to the north, Gen Yahya was chosen to lead the team that helped select the site of Islamabad and interact with Doxiadis Associates, the firm that designed the new metropolis outside Rawalpindi.

Earlier in his career, Gen Yahya was among a group of Indian officers captured by the German Afrika Korps in North Africa and handed over to the Italians as prisoners of war. Gen Yahya used to tell the story of his attempts to escape from captivity and always wrongly denigrated Sahibzada Yaqub Khan for not wanting to participate in the prison break.

He told me the same story in his hospital room in Washington DC when he was recovering from a stroke in his waning days. The author retells the story from Gen Yahya’s somewhat flawed perspective. In fact, Yaqub did try to escape and was caught and kept in an Italian camp. Gen Yahya ended up succeeding in a later escape attempt. A more detailed and accurate story of that period is contained in the detailed account by Maj Gen Syed Ali Hamid in The Friday Times.

Gen Yahya’s attitude reflected the general anti-intellectual biases that pervade the military.

Similarly, the author does not identify Maj Gen Thomas “Pete” Rees as Gen Ayub’s division commander in Burma, when Gen Ayub was sent back for “tactical timidity”, as quoted in my own book Crossed Swords: Pakistan, its Army, and the Wars Within and in a more recent piece in The Daily Star.

The repeat of a risqué joke doing the rounds during the Gen Yahya period, about an alleged assignation with the actress Tarana, is also cited as an actual incident without citing a source. Brig Siddiqi was in a position to give much more of the background to events leading to the downfall of Gen Yahya and how the Pakistan Army did an accurate post-mortem after the end of the lost 1971 war with India, and then buried that report in its general headquarters’ Historical Section, keeping it away even from the new President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

Gen Yahya’s role in halting the Chamb offensive short of Akhnoor is told in general terms, but no new information is provided that would help us understand why and how Gen Yahya decided to delay the offensive by 48 hours, giving India a chance to regroup in that critical sector.

The book conveys a keyhole view of events in the public eye. For example, the aborted March 1, 1971 Yahya speech on a new constitutional arrangement for Pakistan that Gen Yahya failed to deliver himself. As mentioned in Crossed Swords, instead of simply introducing Gen Yahya before his live address on Pakistan’s state television, I was told to read the prepared text written in the first person for him. An announcer read the same text on Radio Pakistan.

Was Gen Yahya inebriated, or was there some debate among his staff about that speech? Why was an attempt made to get back the advance text of that speech from foreign journalists and me? As director of the Inter Services Public Relations Directorate, Brig Sidiqqi was in the inner circle and could have shed light on the behind-the-scenes actions that helped explain the chaotic decision-making in the Yahya cabal. For that, we need to go to other sources, often by authors inside and outside Pakistan, who trawled archives and interviewed participants to connect the dots. If the author had approached Maj Saeed Akhtar Malik, whose father was a celebrated general in the 1965 war, he would have learned the following.

Maj Saeed recounts in an email to me his visit soon after the 1971 war, with Brig Gul Mawaz, a decorated Second World War veteran then retired, when the brigadier recounted two episodes about Gen Yahya and Gen A.A.K. Niazi, the man who surrendered in Dacca [Dhaka]. Gul Mawaz and Akhtar Malik were close friends.

Gul Mawaz recalled to Saeed Akhtar Malik: “I was commanding 103 Brigade in Lahore. Niazi was commanding 5 Punjab under me. I thought he was not up to the mark. Thus, I informed him that I would be initiating a report recommending that he should be reduced in rank.

“Within a week of this, when I returned from office, my batman informed me that Brig Akhtar Malik had driven in from Pindi and was occupying the guest bedroom. In the evening, he brought up the issue of Niazi. ‘Listen, Gul,’ he said to me. ‘I know Niazi is not the most brilliant man in the army, but I assure you he is not the very worst lieutenant colonel either, so can’t you just let him be? After all, there is no danger he will end up being a general, is there?’

“I was amazed that he [Niazi] had brought to my door the only man whom he knew I could not refuse. And so I ‘let him be’, as your father put it, and see what he has wrought!

“But in all fairness, let me also relate to you another story. Yahya, your father, Hamid [whom I hated] and I were all instructors at the Staff College together. More than once, your father confided in me what bothered him about Yahya [with whom I had a deep friendship]. It was his view that Yahya was a nice man, but was so given to drink that he frequently crossed the point where he could not cope with his imbibing. He felt certain that one day he will do himself or his friends considerable harm, if not to Pakistan. But I would always brush off his observations by saying that he was being unduly harsh on good old Agha.

“But when [the 1971] war broke out on the western front, I drove over to the President’s House. It was early evening, and I found both Yahya and Hamid pretty high, in advanced stages of inebriation. I was keen to know what their plans for the western front were. Each time I asked him this, Yahya would brush away the question with a wave of his arm, saying that he was the commander-in-chief who launched his forces, and that it was now up to his generals to fight out the war!

“And then his telephone rang. He picked up the receiver, immediately covered it with his hand, and with the smile of a child who had just received the toy of his dreams, he said, ‘Gul, this is Noor Jehan. She is calling from Tokyo...’

“He then made a request that she sing to him ‘Sayeeon nee mera mahi meray bhaag jagawan aa gaya’.

“As he listened to the song, I sat there, stunned. And then disgusted, I left. I never tried to meet him again, nor to speak to him. I have since often thought over what your father warned me so many years [ago] about Yahya, also about what I had thought about Niazi and the action I was about to take with regard to him till your father dissuaded me.

“I guess, most tragically, we were both right — your father about Yahya, and I about Niazi.” Brig Siddiq mentions this call from Noor Jehan, but without the sourcing or detail and background.

The picture Brig Siddiqi paints of Gen Yahya is of a detached and distracted military chief and president, who was being manipulated by competing cliques of subordinates, and had no clear handle on the centrifugal forces that his poorly informed actions unleashed in Pakistan during his short stint as head of state.

Gen Yahya was increasingly out of his depth in terms of knowledge and intelligence from the field, especially from East Pakistan. He played favourites and allowed others to make decisions on his behalf. Some of his subordinates were involved in political machinations with politicians such as Bhutto. He was failed by his subordinates but, in the end, he was the instigator and owner of that failure. Pakistan suffered inestimable damage as a result.

Any book on the military by a retired officer should help readers and civilians in government better understand the army as the predominant institution in the country. Pakistani military officers are not in the habit of writing rigorous, introspective accounts of key historical events. A lifetime in uniform, imprisoned by strict hierarchy, trains them to expect that rank allows them to substitute assertion for arguments supported by sources and references.

Officers who have tried to write meaningful books risk incurring the wrath of the institution, if they break ranks in terms of accepted narratives or divulge stories that do not accord with the standard ‘truths’. A good example is the magisterial work on the 1965 war by Lt Gen Mahmud Ahmed, a serious and well researched work that he began in 1990 and completed after retirement. The army changed the title of his superb book from Illusions of Victory to an anodyne History of Indo-Pak War 1965, and all copies were removed from the marketplace by the army. Outliers are not tolerated.

Another former director general of the Inter Services Intelligence (ISI), Lt Gen Asad Durrani, is currently feeling the heat for his non-fiction and fiction writings. The nation as a whole is the poorer as a result of these conditions.

Brig Siddiqi’s slim volume moves the needle of knowledge about the Pakistan army only slightly forward. But, we must wait for others to come forth now on more recent history before Pakistan can recalibrate its moves to a future that strengthens centripetal forces and serves a wider national base, rather than pander to regional, linguistic or institutional biases.

Both Pakistan and its army deserve to be much better informed about themselves.

The reviewer is the founding director and Distinguished Fellow at the South Asia Centre of the Atlantic Council in Washington DC and the author of The Battle for Pakistan: The Bitter US Friendship and a Tough Neighbourhood and Crossed Swords: Pakistan, its Army, and the Wars Within www.shujanawaz.com

General Agha Mohammad Yahya Khan: The Rise and Fall of a Soldier 1947-1971

By Brig (Retd) A.R. Siddiqi

Oxford University Press, Karachi

ISBN: 978-0190701413

167pp.

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, January 24th, 2021