The Fragrance of Tears: My Friendship with

Benazir Bhutto

By Victoria Schofield

Oxford University Press, Karachi

ISBN: 978-0190704315

336pp.

Perhaps one of the things the Bhutto family in Pakistan shared in common with the Gandhis in India and the Kennedys in the United States — other than founding legendary political dynasties in different democratic settings — was their virulent fate, which seemed to brand the lives of their successors, to persuade them to keep clear of politics.

Yet all three families are still sticking at it, albeit with different degrees of diligence and success. The slew of literature chronicling the triumphs and tragedies of these political greats, hitting bookshops on an international scale, also corroborates that they are far from being lost in history.

Author, biographer and historian Victoria Schofield’s latest memoir, The Fragrance of Tears: My Friendship with Benazir Bhutto, is, in summation, a literary monument that the author has posthumously built to her Oxford-contemporary and the twice-elected former prime minister of Pakistan. Some may gripe that the narrative is repackaged old wine in a new bottle, or be tempted to compare it to Owen Bennett Jones’s The Bhutto Dynasty: The Struggle for Power in Pakistan — which was released round about the same time. But it would be unfair to reduce Schofield’s work to an overdone and over-sung critically analysed biography when it is, in fact, in the author’s words “My tribute to a friend.”

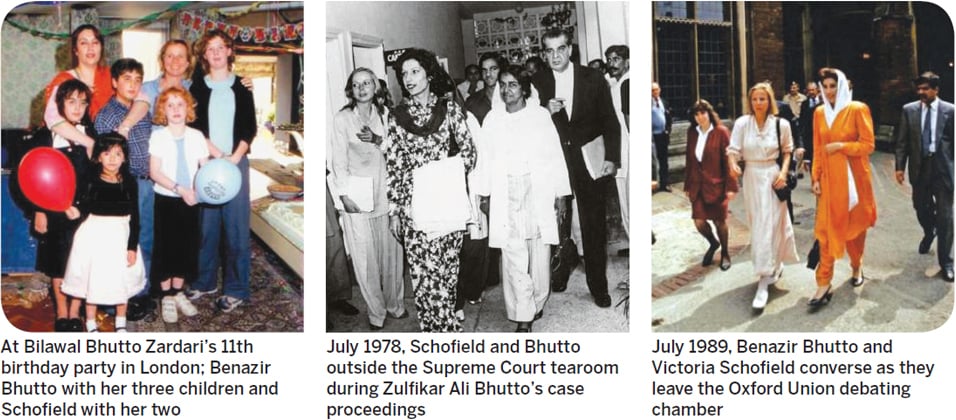

From their first freshers’ encounter at the Oxford Union, to the earth-shattering trial and execution of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, all the way up to dealing with the aftermath of Benazir’s assassination in 2007, Schofield has stood by Benazir’s side. She stood by her through thick and thin, both as an astute observer and confidant, and she lives on to narrate, with great tact and assiduity, a deeply intimate account of an extraordinary woman — but not in the same way as history tells it. Through a three-decade long friendship, Schofield captures, in classic memoir style, Benazir Bhutto as a dutiful daughter, a courageous leader and a friend par excellence.

Victoria Schofield’s latest book is less a critically analysed biography of Benazir Bhutto, and more a celebration of a long-lasting friendship between two women

For those who never had the chance to meet Benazir in person, Schofield lovingly lays it all out. In the rollicking first chapter, ‘Our Salad Days: 1974-1977’, we are offered a rearview mirror reverie of their time as undergraduates at the University of Oxford. Both were enrolled at Lady Margaret Hall and, because of their involvement with the venerable Oxford Union, became fast friends.

Benazir was that slightly older student with an “American intonation” — after having spent four years at Harvard University — who had come to Oxford to read politics, philosophy and economics. Everyone knew she was the daughter of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, then prime minister of Pakistan, but she was not known specifically for it.

“Pinkie”, as she was called, had a fondness for Anna Belinda dresses, drove her friends around in her yellow MG sports car and, if you were lucky, would even whizz you to London to try her favourite peppermint-stick ice cream at Baskin Robbins.

Benazir’s rise to popularity at Oxford came when she was elected as the first Asian woman president of the Oxford Union, by virtue of her gift for delivering powerful speeches — an oratorical skill she inherited from her father. The university, as Benazir wrote in her autobiography Daughter of Destiny, made for some “of the best years” of her life.

Schofield’s prose is lean and clean, sometimes reportorial in the style of German writer and academic W.G. Sebald. This is especially true in the passages delineating the ill-fate of the Bhuttos, such as Zulfikar Ali’s demise at the gallows, which subsequently threw the whole country into disarray, with the 11-year dictatorship of General Ziaul Haq being a political parenthesis in Pakistani history. Or the parts where Benazir is exiled and imprisoned without any contact or communication with the outside world — the ultimate form of social distancing.

Schofield’s friendship with Benazir and interest in the Z.A. Bhutto case set the premise for her aller-retour in Pakistan in the 1970s. She acted somewhat as a professional staffer to Benazir and her family, both locally as well as internationally. She covered the Bhutto trial for The Spectator, a popular British current affairs magazine, and later went on to write her first book on the same topic, 1979’s Bhutto: Trial and Execution.

Her friendship with Benazir also afforded her a portal into South Asia. By 1996, she had published a book on Kashmir, Kashmir in the Crossfire, and is currently one of the most well-respected commentators on South Asia.

The Fragrance of Tears, though undoubtedly straightforward, is loaded with exposition. Because of its delicate pace, it may take a while to reach a scene that crackles with excitement. However, it is only through such exposition that one is able to sieve out its hidden gems and Schofield is a maestro in her ability to parcel out information at just the right time. After all, it is a book that simply celebrates a friendship between two women that took up much of their adult life, with one whose life was marked by tragedy.

At times, it feels as though Schofield deals cogently with French philosopher Jacques Derrida’s The Politics of Friendship, with themes of loss in friendship. To quote Derrida: “[This is] the mourning that is prepared and that we expect from the very beginning...” Indeed, a combination of loss with the element of surprise makes for one of the most moving parts of the memoir. Little did Schofield and Benazir know that October 2007 would be their swan song.

When it comes to Bhutto’s family, although Schofield touches upon Benazir’s relationships with her brothers — the bad boys who started their own political party, Al-Zulfiqar, and broke away from Benazir and the PPP — she does not explore their tumultuous relationship and the mysterious cause of Murtaza Bhutto’s death, which remains one of Benazir’s biggest controversies. Or what her marriage to Asif Ali Zardari was like. All these parts may be missing, but it is only an extension of Schofield’s loyalty to her friend beyond death.

The author writes with poise and passion and shapes The Fragrance of Tears as both a catharsis and a coming to terms with her past. She seems to describe a bygone way of being, one racked with less anxiety about the ties that hold us together as it is, above all, a book that honours and celebrates a friendship. But with the unforgettable tragedy that befalls Benazir, tears are bound to stain the page.

The reviewer is the digital director of the Lahore Literary Festival

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, March 28th, 2021