Nasa hopes to score a 21st-century Wright Brothers moment and make history on Monday as it attempts to send a miniature helicopter buzzing over the surface of Mars in what would be the first powered, controlled flight of an aircraft on another planet.

Landmark achievements in science and technology can seem humble by conventional measurements. The Wright Brothers' first controlled flight in the world of a motor-driven airplane, near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in 1903 covered just 37 meters in 12 seconds.

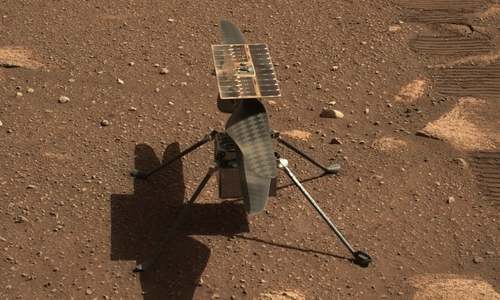

A modest debut is likewise in store for Nasa's twin-rotor, solar-powered helicopter, Ingenuity.

If all goes to plan, the 1.8 kilogramme whirligig will slowly ascend straight up to an altitude of three metres above the Martian surface, hover in place for 30 seconds, then rotate before descending to a gentle landing on all four legs.

While the mere metrics may seem less than ambitious, the "air field" for the interplanetary test flight is 278 million kilometres from Earth, on the floor of a vast Martian basin called Jezero Crater. Success hinges on Ingenuity executing the pre-programmed flight instructions using an autonomous pilot and navigation system.

"The moment our team has been waiting for is almost here," Ingenuity project manager MiMi Aung said at a recent briefing at Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) near Los Angeles.

Nasa itself is likening the experiment to the Wright Brothers' feat 117 years ago, paying tribute to that modest but monumental first flight by having affixed a tiny swath of wing fabric from the original Wright flyer under Ingenuity's solar panel.

The robot rotorcraft was carried to the red planet strapped to the belly of Nasa's Mars rover Perseverance, a mobile astrobiology lab that touched down on February 18 in Jezero Crater after a nearly seven-month journey through space.

Although Ingenuity's flight test is set to begin around 3:30am Eastern Time (ET) on Monday, data confirming its outcome is not expected to reach JPL's mission control until around 6:15am ET on Monday.

Nasa also expects to receive images and video of the flight that mission engineers hope to capture using cameras mounted on the helicopter and the Perseverance rover, which will be parked 76m away from Ingenuity's flight zone.

If the test succeeds, Ingenuity will undertake several additional, lengthier flights in the weeks ahead, though it will need to rest four to five days in between each flight to recharge its batteries. Prospects for future flights rest largely on a safe, four-point touchdown the first time.

"It doesn't have a self-righting system, so if we do have a bad landing, that will be the end of the mission," Aung said. An unexpectedly strong wind gust is one potential peril that could spoil the flight.

Nasa hopes Ingenuity — a technology demonstration separate from Perseverance's primary mission to search for traces of ancient microorganisms — paves the way for aerial surveillance of Mars and other destinations in the solar system, such as Venus or Saturn's moon, Titan.

While Mars possesses much less gravity to overcome than Earth, its atmosphere is just one per cent as dense, presenting a special challenge for aerodynamic lift. To compensate, engineers equipped Ingenuity with rotor blades that are larger (1.2m-long) and spin more rapidly than would be needed on Earth for an aircraft of its size.

The design was successfully tested in vacuum chambers built at JPL to simulate Martian conditions, but it remains to be seen whether Ingenuity will fly on the red planet.

The small, lightweight aircraft already passed an early crucial test by demonstrating it could withstand punishing cold, with nighttime temperatures dropping as low as 130 degrees below zero Fahrenheit (minus 90 degrees Celsius), using solar power alone to recharge and keep internal components properly heated.

The planned flight was delayed for a week by a technical glitch during a test spin of the aircraft's rotors on April 9. Nasa said that issue has since been resolved.