Living in its glorious royal past, the laid-back district of Bahawalpur has everything an area can ask Mother Nature. Its history dates before the Indus Civilization and it has a massive riverine region as it falls on the southern bank of River Sutlej. While it has a huge irrigated landscape, two-thirds of the district is desert, and it also has forestry and wildlife second to none.

However, the district has refused to grow beyond its agricultural and rural past. Its industrial base remains thin, rather nonexistent. Its agriculture is archaic, going through confusing times — abandoning old ways but not finding new ones. It has internationally acclaimed breeds of large and small animals but they are yet to be viable commercial entities and exotic breeds simply do not survive in its harshly high and dry temperature — ruling out large scale dairy farming and industry.

Its sociology — steep and self-perpetuating division among local and migrated population — even after hundreds of years of mingling is case study material for students of anthropology.

Historically, agriculture in the Bahawalpur district revolved and evolved around cotton. Out of its total net sown area of 980,449 acres, cotton hogged 675,000 acres till as late as 2015. The next five years, however, started witnessing a drop. The triple crisis (low-quality seed, diseases — both sucking pest and, of late, fungus — and market failure), which triggered the fall in other parts of the country, hit Bahawalpur as well and the district started losing its cotton confidence and identity. Despite the decline, it is still among a few districts sticking to cotton, mainly because of a lack of alternatives than the love for cotton.

Cotton is a difficult crop — it takes 16 steps to mature. If one step is missed or mishandled, the yield suffers badly. Another step is messed up, financial loss starts. The alternatives are easier to grow, financially lucrative and more certain sources of income, therefore they are emerging, albeit slowly

“These are confusing times — cotton does not serve the purpose nor have alternatives emerged clearly. We are at an agricultural crossroads,” says a local farmer. Cotton, despite the trouble, is still sown on a little less than 600,000 acres. Its acreage, however, fluctuates according to returns on competing crops like maize, sugarcane and rice; cotton makes the adjustments in acreage, he says.

The crops slowly eating into the cotton area are rice, maize, sugarcane and oilseeds — water guzzlers and highly exhaustive alternatives. In five years, rice has grown from 36,000 acres to 52,000 acres. Oilseed crops have jumped from 245,000 acres to 458,000 between 2015 and 2020. Maize during the same period raced from a

mere 10,000 acres to 53,000 acres. Sugarcane, however, has been almost constant: hovering just above 50,000 acres. Alternatives are thus emerging but not as fast as in other districts in South Punjab, like neighbouring Rahim Yar Khan.

Khurshid Zaman Qureshi, former provincial agriculture minister, narrates the tale of the defeat of cotton. “In the first decade of this century, we introduced bacillus thuringiensis (BT) variety with high hopes. However, technological up-gradation failed to keep pace and the entire experiment fell apart due to weak seeds, pest attacks and market failure. The traditional varieties were low yielding but fit the district’s realities — low tech, less water and laid-back practices. The BT needed all that the district and its people did not have: more water, careful tending and continuous technological up-gradation. These factors failed cotton and the crop failed its farmers. The story got completed when more lucrative options sneaked in and co-option began. That is precisely where agriculture stands in the district.”

The local chief of the agriculture department, Jamshaid Khalid, substantiates Mr Qureshi’s claim: “Cotton is a difficult crop; it takes 16 steps to mature, you miss or mishandle one and the yield suffers badly. You miss another one and financial loss starts. The alternatives are easier to grow, financially lucrative and more certain sources of income. So, they are emerging, albeit slowly.

Iftikhar Haider, a local progressive farmer, explains the compounding confusion: “The district was late in looking for alternatives to cotton. By the time it woke up, new technology in crops like maize, which promoted it in the first place, had lost its sheen and financial return had already entered the period of diminishing returns. With low water allowance in the south (3.6 cusecs per 1,000 acres) as compared to the north (read rice region), Bahawalpur could not afford to go beyond a certain limit. Its sandy lands and far less rain, as compared to the rice belt in the north, only ensured all kinds of limits on maize, sugarcane and rice expansion.

“Where to go? Vegetables have entered the scene. But it is a capital-intensive venture. Tunnel at one-acre costs around Rs3 million and crops needs intensive care. They are paying, but only after the heavy investment of capital, man-hours and expert handling. Unable to decide where to go, the district is still clinging to old ways. Trouble is, they serve the farmer no more”.

The livestock picture of the district is not very rosy either. This is despite the fact that two-thirds of the district is a desert, with potential for livestock. Considering this possibility, the previous government created four farms (5,000 acres each) in Cholistan and they were to be declared disease (foot and mouth) free and directly connected to exporters. The experiment, however, fell apart with the exit of the PML-N government.

The population figures tell a routine story; 1.25m larger (925,822 cattle and 328,559 buffalo) animals, little less than a million small (goat 768,348 and 228,276 sheep), 629,403 poultry birds, with 56 broiler and eight layer farms.

“Only local breeds of animals survive the scorching desert temperature, which goes as high as 50 degree Celsius during summers,” explains Malik Naeem, who tried and quit dairy farming. All these breeds yield no more than seven to eight litres of milk a day, which does not make commercial sense. The imported ones, which can yield up to 30 litres a day and justify the investment, do not survive without massive additional cost for protection. That is why there are no mentionable dairy farms or industry — milk, butter or cheese units.

However, the promise of meat and beef is huge. The district does need modern slaughterhouses and meat processing units. But they have not been established because the locals hardly try innovative ideas, both in business or agriculture, he concludes.

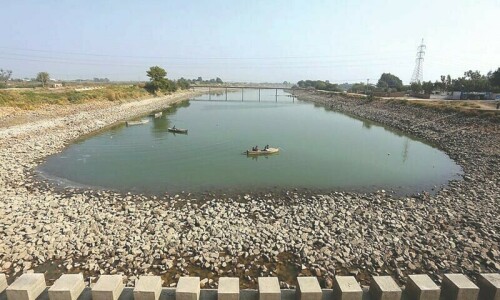

The district also falls in the twilight zone as far as water is concerned. The five canals — Lower Bahawal from the Indus zone and Upper Bahawal, Qaim, Eastern Sadqia and Qaim from the Mangla zone — serve the district. Occasional flooding temporarily revives Sutlej, replenishing the district aquifer. These factors have saved it from entering the disaster water zone. A relatively limited number of acreage in sugarcane, maize and rice has also saved its water so far. If and when these crops claim more areas, water, which is still available at 30 to 50 feet depth, is sure to race down as it happened in almost all neighbouring districts.

Published in Dawn, The Business and Finance Weekly, April 26th, 2021