One of the most influential Islamic scholars to emerge in South Asia is also perhaps the most enigmatic. Despite being the architect of arguably the region’s largest Sunni sub-sect — the Barelvi — his name hardly ever crops up in the many discourses on Islam in Pakistan.

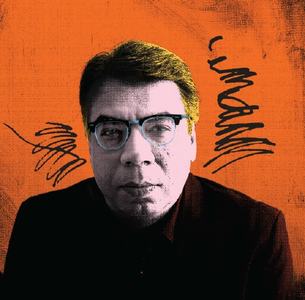

The scholar is Ahmad Raza Khan Barelvi. Various books on his life have continued to appear after his death in 1921. The most recent was published this year. Authored by Anil Maheshwari and Richa Singh, it is perhaps the only biography of the scholar written in English.

But Raza Khan remains a sideshow compared to other giants such as Abul A’la Maududi, Fazlur Rahman Malik, Ghulam Ahmad Pervez, Dr Khalifa Abdul Hakim, Javed Ahmad Ghamidi, Israr Ahmad and Amin Ahsan Islahi. Some came from the right and some from the left, but almost all of them were invested in deciphering Islamic scriptures through modern political and economic ideas, largely Western.

For example, Maududi (d.1979) borrowed heavily from the 19th century German philosopher Friedrich Hegel’s notion of the ‘ethical state’ to construct his theory of ‘hakumat-i ilahi’ (the rule of God or an Islamic State). Meanwhile, Fazlur Rehman Malik (d.1988) looked to emphasise the ‘inherently progressive’ nature of Islam by reviving the ideas of the 9th century rationalist school of Islam, the Mutazila. And like the 19th century Muslim reformer Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, Malik merged these ideas with the economic and political modernity of European Enlightenment that promulgated the importance of rational thought and science.

But why is Ahmad Raza’s name not as widely known as that of the Muslim modernists, political Islamists, Deobandi and so-called ‘Wahabi’ scholars? Compared to the Barelvi, these represent minority segments within the country’s Sunni majority.

Ahmad Raza Khan Barelvi is seen as an influential Islamic scholar and the founder of the largest sub-sect among Sunni Muslims in the Subcontinent, the Barelvi. So why does he remain mostly unstudied?

After going through biographies of Ahmad Raza that were available to me, I believe one of the problems lies in how they are phrased. In each one of them, substantiated facts about Raza’s life are often squeezed between a plethora of sentences that describe him in an overly superlative manner. It becomes hard for the reader to separate fact from fiction. Same is the case in literature that criticises his ideas. The attacks on him are so vehement, they smack of sheer retaliation rather than an intellectual retort.

But here also lie answers to the question about Raza’s relative obscurity. I say ‘relative’ because he was a prolific writer and a lot of his written work is readily available, but it is hardly ever the topic of discussions in the academic discourses on Islam in Pakistan. Even Western academics writing about the evolution of Islam in Pakistan only rarely mention him.

Outside Raza’s hyperbolic biographies, he can be found more clearly in his own writings. Most of them are as vehement as those of his detractors. In his works, Raza comes across as a man with an extremely sharp intellect and an equally sharp vocabulary. A man with an abundance of knowledge of classical Islamic theology. Most interestingly, he brilliantly uses powerful logic to counter critics, and yet, he does not see any contradiction in many of his claims that border on the preternatural.

It was these that attracted the wrath of the ulema of other Sunni sub-sects who saw his work as being obscurantist. They accused him of trying to barricade the ‘decaying’ strand of South Asian Sufism against reform.

Raza was born in 1854 in Bareilly during a period when the centuries-old Muslim rule in India had receded and the region was firmly in the hands of the British. Raza never attended a madressah. As a young man, he became a disciple of some Sufi teachers (pirs).

Raza’s writings are almost entirely aimed at his critics. Time and time again he used his reservoir of theological knowledge to counter every Islamic sect and sub-sect whose theologians disagreed with him. In the process, he organised a large set of beliefs and rituals that, for centuries, had been evolving among the Muslims of India. These, or the way Raza redefined them, can still be seen in practice among the Barelvi.

In his writings, he also comes across as a man who could rapidly move from applying sharp logic to rationalise many of his somewhat anomalous declarations, and then, in the most ferocious manner, cut down those who disagreed with him. In a 1906 book, Husamul Haramain, he went to the extent of declaring many of his detractors as being ‘beyond the pale of Islam.’ He too faced similar accusations.

Raza was a prominent figure within the Islamic discourse between the modernist, Deobandi, Shia, Ahle Hadees and Ahmadiyya scholars of India. He was the figurehead of the ‘folk Islam’ of the region which began to be known as Barelvism. So what was really behind the curious phenomenon in which, despite his propagated beliefs overpowering those of his critics, the memory of his name got diluted?

Largely it was because of the manner in which he rejected joining the Khilafat Movement, which had sprung up after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in 1919, at the hands of the British. Deobandi ulema demanded the restoration of the Ottoman caliphate. They were joined by Indian nationalists.

Raza forbade the Barelvi from joining the movement. He said he could not be part of a movement led by pan-Islamists and the Deobandi who, Raza claimed, were being exploited by Hindu nationalists. His refusal to boycott British products saw him being labelled as pro-British.

Raza passed away in 1921. Though opposed to entering politics, some of his immediate successors decided to take part in the ‘Pakistan movement’, which was opposed by Maududi and various Deobandi ulema for being ‘secular-nationalist.’

Raza’s prescribed rituals are very much alive, especially among the working classes, the lower-middle classes and rural Barelvi. And thanks to the speeches of the late leader of the Tehreek-i-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP), Khadim Hussain Rizvi (d.2020) who often quoted Raza, the scholar’s name has whetted the interest of historians who, for the first time in decades, have begun to academically investigate Raza’s works.

Raza had a great distaste for politics. But Rizvi expanded his idol’s ideas by politicising them, because he believed the Barelvi had been treated wrongly by a country whose creation they had supported.

Rizvi did not heed Raza’s warning, which he had expressed during the Khilafat Movement. Raza feared that political militancy could be the undoing of what he believed was the only true version of Islam — his own.

Published in Dawn, EOS, June 27th, 2021