Balwant Singh — born 100 years ago last month in Chak Bahlol, Gujranwala district — wrote in both Urdu and Hindi. At the time of his death he had to his name 11 books in Urdu — seven collections of short stories and four novels — and 30 books in Hindi. Several of these books are republished now and again.

Initially, Singh’s books were published from Lahore but, later, Allahabad became the centre of his life. In 1975, suffering from ill health, he sold his ancestral hotel at Allahabad Chowk — by then his sole source of income — and, over time, his vision also deteriorated.

When he passed away in 1986, at the age of 65 in a state of despair, hardly a writer was present to carry his corpse. His death occurred quietly and, even when the news came out, except for one or a half piece of writing, no one remembered him much. Novelist Upendranath Ashk did broadcast speeches on Singh’s short stories and published an essay on him in the journal Alfaaz, and a very short article about Singh appeared in the journal Kitab Numa. This was the entirety of the tribute paid to an important artist! What can one say about this except ‘Fa-a tabiru ya ulil absar’ [See and learn, O you who have sense]!

Singh was considered a romanticist, though this fact is as right as it is wrong. From a sketch of his life, one can guess he was extremely self-respecting and a man comfortable in his own skin. The time he lived in Lahore was the period of his playfulness. A handsome and robust man who rode around in a rickshaw with an Alsatian at his feet, he would meet Krishan Chander, Rajinder Singh Bedi and Maulana Salahuddin Ahmed, but he was perhaps not in the habit of visiting people and never made many friends.

Balwant Singh’s centennial birth anniversary prompts a revaluation of the oft-ignored Urdu and Hindi writer who never got his due

Even during his employment with the newspaper Aaj Kal in Delhi, he remained very much aloof; he had an intense feeling that he was more intelligent and competent than Arsh Malsiyani and Jagan Nath Azad, and that he was not given his due.

So, becoming a victim of workplace conspiracies, he had to relinquish his employment with Aaj Kal and relocate to Allahabad but, according to Ashk, here, too, he remained unsociable. He never corresponded much with others and, if he did, that correspondence has yet to appear on the scene.

In order to understand the mind and art of Balwant Singh, it is important to know that he felt insecure and incomplete vis-a-vis his peers. As time passed and circumstances forced him from Lahore to Delhi, then threw him from Delhi to Allahabad, he shrank further within himself. The more he shrank, the more he wrote and delighted in the world created of his own imagination.

In the period in which Singh began his literary life, new writers either followed one or the other trend, or walked on paths set by Chander, Bedi and Saadat Hasan Manto. But Singh determined a separate path for himself. His first volume of short stories, Jagga, highlighted the minutiae of Sikh society — a first in the genre of Urdu short fiction.

‘Jagga’ is ostensibly the story of a dacoit, but away from the colour of thievery, it tells of some serious facts of life. Another tale in this collection — ‘Sazaa’ [Punishment] — can be considered a ‘complete short story’, in that it meets the critical criteria of the genre in every aspect. In his second collection, Taar-o-Pood [The Warp and Woof], Singh’s experiences achieve greater breadth and he comes forth as a mature writer.

‘Samjhauta’ [Compromise], ‘Deemak’ [Termites], ‘Granthi’ [Granth Reader], ‘Beemaar’ [Sick], ‘Khalaa’ [Void] and ‘Punjab Ka Albela’ [The Fop of Punjab] are some of his memorable Urdu short stories. From another collection titled Sunehra Des [The Golden Land], the stories ‘Lams’ [Touch], ‘Khuda Ki Vasiyat’ [The Testament of God], ‘Babu Manik Lal Ji’ and ‘Chakori’ similarly add weight to the historical corpus of the Urdu short story.

The greatest characteristic of Singh’s stories is their variety. The writer had seen life from multiple aspects and attempted to understand and explain many of its problems. He was skilled at characterisation and several of his creations — Jagga, Albela, Babu Manik Lal — illustrate opposing conditions of human life as the writer took care to bring out their contradictions rather than allowing them to appear uniform.

According to critic Mumtaz Shirin, “There are very few characters in Urdu that can remain alive after being separated from the short story.” Meanwhile, ‘Rang’ [Colour] and ‘Baazgasht’ [Echo] are studies of the human psyche that leave a profound impression on the reader’s mind.

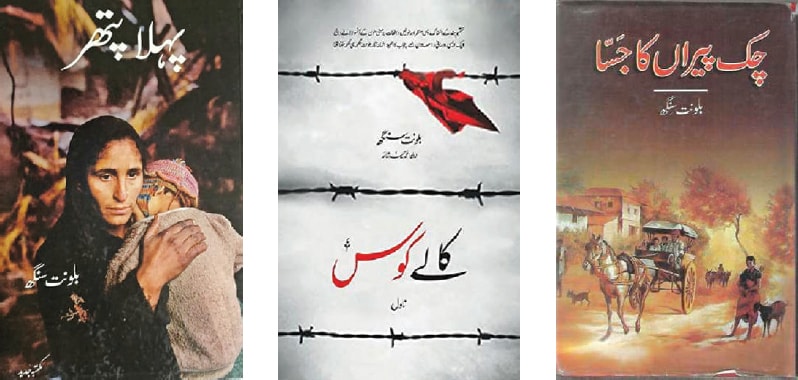

Among Singh’s later short stories, ‘Baba Mehnga Singh’, ‘Kaalay Kos’ [Long Leagues], ‘Webley 38’ and ‘Pehla Pathar’ [The First Stone] are of very high quality. His writing was polished further after Partition, his experiences and observations are never stale or repetitive and appeal equally to the average person as well as the literary intellectual.

This essay is an attempt to cast a glance at the various facets of Balwant Singh’s art of storytelling. The Urdu short story is akin to a rainbow, where several colours come together to create a beautiful whole. Though not given much importance during his life, and very much forgotten after his death, Singh holds a key place in the rainbow of the Urdu short story — distinct from others, but very much necessary in the spectrum. However, his contemporaries — Manto, Bedi, Chander and Ismat Chughtai — overshadowed the horizon and Singh was unable to receive his due. The reason was partly his own reclusiveness, but mostly that his works were published in Hindi, and Urdu soon forgot its foppish artist.

Let’s discuss Singh’s art step-by-step. Prima facie, he appears a romanticist. His more successful stories feature male Sikh characters of extraordinary stature and attributes, unparalleled in power and bravery, heralds of virtue, sacrifice, goodness and dignity. Thus, these are cultural alter-egos, an imagination of the interpretation and security of racial and territorial desires and wishes.

The hero is somewhat of an administrator figure, supplying a standard of bravery or manliness to groups or tribes. But this is not the full picture. Usually, these allegorical heroes deride themselves. They, or the characters moulded upon them, defeat the values for whose security they are interpreters.

For instance, Jagga, the protagonist of Singh’s best-known story, is presented as a fearsome and grotesque dacoit. Falling for the village damsel Gurnaam, he attempts to change, but unfortunately for him, Gurnaam loves another. When Jagga discovers this, he attacks the youth. However, upon realising that their love is true, Jagga himself mediates between Gurnaam’s father and the youth to arrange their marriage. Thus, the values here are not just bravery, manliness and passion, but also hospitality and the honouring of one’s promise.

Writing on Singh’s first collection a few years before Partition, Rajinder Singh Bedi said: “Balwant Singh presents variety in his theme, beauty in writing and such a new angle at every moment that our aesthetic sense becomes happy reading it.”

This opinion is true in every respect. Although his novels outnumber his short story collections, Singh’s skills are at their peak in short fiction. His novels were not as successful, and we can agree with Ashk when he says, “there is enough looseness in his novels, there is a lot which is created fictitiously and far from reality. But his stories are entirely free from this weakness.”

It is a great misfortune that due attention was not given to Singh’s work when he lived. After his premature death, he more or less became invisible. However, with respect to the creation of the chronology of the Sikh psyche and cultural significance, and as the creator of ‘Jagga’, ‘Granthi’, ‘Soorma Singh’, ‘Webley 38’, ‘Pehla Patthar’, ‘Desh Bhagat’ [Patriot], ‘Kali Teetari’ [The Black Partridge] and ‘Kathan Dagariya’ [Difficult Road], Balwant Singh’s place in the Urdu short story is secure.

The acceptance and significance of his very special stories will increase with time, not decrease. And on his birth centenary, one can also say with confidence that, even if such a short story writer can very much be overlooked on an accidental basis, time can never perpetually overlook Balwant Singh.

The writer is a Lahore-based social scientist, translator, dramatic reader and president of the Progressive Writers Association in Lahore. He is currently working on a book, Sahir Ludhianvi’s Lahore, Lahore’s Sahir Ludhianvi. He can be reached at razanaeem@hotmail.com

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, July 11th, 2021

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.