Despite being a small district Matiari is socio-economically and culturally vibrant. Without mentioning Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai, a mystic saint, the profile of the Matiari district would always be incomplete. The sufi’s shrine is located in Bhitshah — a town known internationally where men and women with mystic leanings from different parts of the world throng every 14th of Safar, a lunar month, to pay their respect to the great poet who preached universal love and peace. Bhitai was born in the Matiari district.

The shrine of saint Makhdoom Sarwar Nooh is another potential source of spiritualism in Hala. So, Matiari has two spiritual power centres — Nooh and Bhitai. While the former has deep political roots, the latter is known for devotion. Sarwar Nooh’s shrine is headed by Makhdoom Jamiluzzaman of Hala’s Makhdoom family in line with the spiritual order.

“Bhitai had to leave Hala Haveli because of unpleasant conditions and the indifferent attitude of his contemporaries in the area where he was born,” says Hamid Akhund, a former Sindh secretary culture with a deep interest in Sindh’s heritage and culture.

Agriculture figures indicate that while cotton is faced with a decline in acreage in many districts, it is faring better in Matiari

“Bhitai then arrived at Bhitshah where according to one legend he dug the present Karar Lake to create a bhit [dune] out of its soil,” says Mr Akhund. Bhitai then settled at that dune and was buried there. And that’s how he was called Shah of bhit (dune) or Bhitai, a man who lives on the dune.

Matiari district’s famous town, Hala is home to handicrafts, kashi tiles, embroidered colourful charpoys and handmade fabric of soosi_ a female stripped cotton and khadi, for men’s wear made of cotton and silk yarn.

The handmade fabric produced by khaddi (pit looms) is facing extinction as power looms have emerged in substantial numbers in the city. Khaddis used to number in hundreds in Hala once. Artisans are also associated with the old art of Sindhi Ajrak woodblock printing in Matiari and Hala.

“Businesses of these handicrafts, clothing and kashi tiles have been quite popular but fast losing their charm,” says Mr Akhund, who also overlooks Sindh Indigenous and Traditional Crafts Company (Sitco), sponsored by the Sindh government. Sitco seeks to revive these crafts which were the identity of various cities of Sindh.

Mr Akhund, however, concedes Sitco is not getting the desired response from craftsmen for a variety of reasons, primarily involving commercial viability and the laborious nature of work. “Next generation of artisans are no longer interested in continuing with the work,” he remarks.

“New generation of artisans prefer a mechanised form of work to produce handicrafts. Everyone has a commercial approach and rightly so as, after all, it is about one’s economic needs,” he says.

For instance, he adds, only one man who is at an advanced age now is still associated with handmade soosi and khadi production. “He is doing it as he loves it since he inherited the art from his family,” Mr Akhund says. The same goes for the making of kashi tiles for which the required expertise is hardly available. Tiles production involves multiple stages and a particular sort of soil and wood which is used in a furnace.

Located on the left bank of the Indus river off the National Highway, Matiari had become an independent district in 2004 in the Musharraf regime when Hyderabad was divided into four districts — Tando Allahyar, Matiari, Tando Mohammad Khan and Hyderabad.

Many dissenting voices were heard against the administrative division arguing that this plan would not work. However, this has indeed paid off. People of the three districts, Matiari, Tando Allahyar and Tando Mohammad Khan are now better off.

Makhdooms, Jamotes and Memons live here in large numbers besides Arbabs, Jamalis, and Rahus. Formidable Makhdooms and Jamotes have a bigger share in landholdings here and dominate the political scene. Lately, Memons — backed by Jamotes — took on Makhdooms in 2013 to make a run for electioneering.

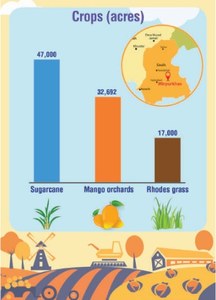

Matiari has a diversified agricultural landscape, offering adequate farm opportunities with the best soil quality for major crops as well as orchards. Some minor crops like onion add value to the farm sector. Matiari is fed by the perennial Rohri Canal, considered to be mini-Indus.

Finer quality of soil is attributed to the fact that the area has remained an old course of river Indus which had also flowed once near Brahamanabad or Mansura — conquered by Mohammad ibn Qasim — in Sanghar district, bordering Matiari. Cultivation of three major crops — wheat, cotton and sugarcane remains intact. Drainage issues emerge in case of heavy rains, like in 2011. Groundwater is brackish in some patches.

The area has a sugar factory owned by Jamotes. Its management is known for starting sugarcane crushing every season regardless of the Sindh government stance on timing and sugarcane’s indicative price. In view of the considerable production of cotton, six cotton-ginning factories exist, too.

“The sugar factory management has upgraded mills’ crushing capacity. Jamotes are also catering to healthcare needs of the local population on their own by launching some quality healthcare support,” remarks a progressive grower from the area, Haji Nadeem Shah.

Agriculture figures indicate cotton is faced with a decline in acreage in many districts but it is faring better in Matiari. Since 2008-09 when 37,200ha were brought under its cultivation the acreage increased to 37,800ha in 2009-10 (the year when Sindh had produced the highest cotton production of 4.2 million bales) 39,550ha in 2010-11; 38,000ha in 2011-12; 40,500ha in 2018-19. In the 2020-21 season, sowing on 41,000ha was achieved, which is good news for Matiari. Sugarcane is also doing well.

Mango and banana farming continue by growers with larger landholdings. Nasarpuri variety of onion is popular. Onion from Nasarpur and other pockets of Matiari is harvested early and transported to Punjab in addition to sizeable exports. Onion’s harvest at times coincides with the import of veggies to the chagrin of growers.

The business of mava, condensed milk, is Matiari’s peculiarity and has commercial viability. “We sell mava and its ice cream to organisers of large weddings in cities other than Matiari as well,” says the owner of one such business in Matiari city.

In terms of Sindh’s livestock, Matiari’s share is assessed at 2.82 per cent with 1.55pc cattle and 1.27 of buffalo as per the Sindh livestock projected population of 2018.

Once Matiari used to have a rich riverine forest cover but the forestland has fallen prey to encroachments. After the new 2005 forest policy, forestland was also occupied illegally for agriculture purposes by influential personalities who established their ketis there, narrowing the floodplains.

Lately, the forest department launched an operation for the retrieval of forest lands under the Sindh High Court’s directives. But until Aug 2021, 1,426 acres of forestland were being used for unauthorised agricultural purposes in Matiari.

Published in Dawn, The Business and Finance Weekly, September 13th, 2021