Price controls have always been popular with politicians in countries like Pakistan because of their widespread appeal and the fear of political fallout of surging prices, particularly in times of soaring inflation and shortages. Even after the country was put on the path of economic deregulation and liberalisation in the early 1990s, successive governments have continued to fix consumer prices of a whole range of commodities and products.

Where they find it difficult to impose direct price controls because of one reason or the other, the politicians use other means like direct intervention in the market to hold down the prices at a ‘desirable’ level’ even when not all consumers consider the determined price level as fair to them.

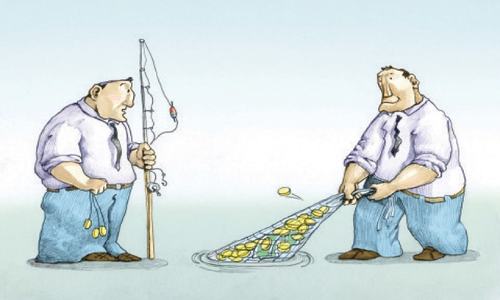

But price controls never work; rather they upend the supply and demand equilibrium and seldom protect consumers. Actually, the negative implications of price controls far exceed the benefits — if any — to consumers. Such kneejerk actions mostly result in shortages — and consequently raised prices — owing to the sudden increase in demand, as we have experienced multiple times in case of sugar and wheat flour crises, recent and past.

The experts also argue that price controls provide incentives for hoarding, black-marketing, production cuts, etc, forcing many consumers to pay a lot more than what they would have to pay for a product if the price controls were not in place. The regulation of drug prices, for example, has invariably resulted in the disappearance of cheap life-saving medicines from the market. More importantly, the prices rise more rapidly once the controls are lifted as hidden inflation surfaces suddenly, subjecting the consumers to a greater economic pain after a short-lived, temporary relief. It goes without saying that price controls also regulate the consumption patterns in an economy, making investment decisions difficult.

Price controls also regulate the consumption patterns in an economy, making investment decisions difficult

The recent government decision to introduced Price Control and Prevention of Profiteering and Hoarding Order, 2021 based on the 44-year old Price Control and Prevention of Profiteering and Hoarding Act, 1977, last month declares 50 goods, including daily essentials such as tea, milk, sugar, edible oils, meat and wheat, and industrial and agricultural inputs ranging from caustic soda, soda ash, cement, automobiles, tractors, chemicals like pesticides and fertilisers, steel and cotton lint to structure their prices in the hope of curbing headline inflation. Sounds silly or funny? It also defines the ‘situation of uncontrolled price hike’ with an average rise of not less than 33 per cent in their prices from the preceding year as an ‘emergency’ just like a situation of war, famine or natural calamity — to justify the price curbs if and when imposed.

The order gives district administration officials powers to enter and search any premises of any trade association and verify information provided by such association, as well as to fix the price. The order can easily be interpreted as an indication of the government’s lack of trust in the working of the regulators like the Competition Commission of Pakistan, Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan and so on.

The businesses have rightly opposed the order, saying the policy risks jeopardising and disrupting the supply chain of industrial and agricultural products since the operations of manufacturers and importers will become unsustainable with the introduction of price caps. “The government move to arrest inflation through the application of some form of price controls on selected goods defies basic economic principles,” commented a leading businessman on condition of anonymity.“Capping prices will not ensure supply or affordability for all. This is not how markets work.”

The policy is also vague as it aims to fix prices of the commodities using a cost-plus method after conducting consultative meetings with the representatives of key producers and their representative associations. In other words, the producers are allowed to pass the rising cost of doing business on account of increasing domestic and other prices or global commodity (raw material) prices to the consumers.

Recently, the government stopped one automobile assembler from raising its prices and has sought justification from market players for price adjustments. According to the automotive manufacturers, the costs of key inputs such as steel sheets, aluminium and forgings have increased by up to 36pc in the last five months. This is in addition to more than 10pc currency devaluation in the last four months.

‘The government should focus on improving market structure rather than interfering in the market and distorting the demand-supply dynamics,’ says an auto manufacturer

“How will the industry survive and become sustainable if it keeps on absorbing these price increases?” a manufacturer wondered. “The government should focus on improving market structure rather than interfering in the market and distorting the demand-supply dynamics.” The steel industry also claims to have so far absorbed significant global price pressure in its domestic prices.

A Karachi-based analyst commented that the food prices in Pakistan have increased primarily because of imported inflation. “The government needs to improve the agriculture productivity and the food supply chain as repeatedly noted by the central bank in its reports and monetary policy statements instead of capping prices as this move will not yield the desired results.”

Sadly, says a Lahore-based businessman, the policies in Pakistan are made based on sound-bites by bureaucracy without consulting businesspeople. “Instead of doing their job of enforcing existing policies and laws, the bureaucracy always finds it easier to change them and penalise the business for their incompetence. As a result of frequent policy shifts and changes in laws, we have put in place an environment that discourages investment and encourages corruption, a killing combination for any economy.”

“The country cannot claim to be business-friendly by just repeating the refrain; its economic and business policies and their implementation must reflect it. The mindset has to change to effectively face the challenges facing the economy. It is about time that policy- and law-making is based on research and supported by data. Professional structures need to be in place and then be respected. Implementation has to be monitored and systems need to be in place to evaluate the success or lack of it. Knee jerk reactions to situations and personal judgments of individuals, no matter how big they are in the hierarchy, should not matter,” he added.

Published in Dawn, The Business and Finance Weekly, September 13th, 2021