My index finger shoots up. “Once more, please,” I say, hunching towards the Macbook facing me on a table a few feet away.

“It’s not quite finished, but you’ll get the idea,” director Nabeel Qureshi says. And yes, two text placeholders were repeated and the sound needed slight balancing (it might have been the distance or the speaker) but, for the most part, the trailer for Khel Khel Mein (KKM) was ready.

And it’s a surprise. In a good way, that is.

A dramatic beat rapid fires important visual cues: people — one of them Sheheryar Munawar in a ’70s hair-do and moustache — scurry off a beach; a plane nosedives over his head; kneeling prisoners in a concentration camp are being executed; bodies of dead men, women and children lie on the floor. This is pre-separation Bangladesh.

The first Pakistani cinematic release in over two years since the deadly coronavirus pandemic hit, Nabeel Qureshi and Fizza Ali Meerza’s Khel Khel Mein marks 50 years of the secession of East Pakistan

Without warning, the story jumps to the present. The colour palette is cleaner and vibrant. Men and women are hipper and happening. They’re today’s college-going youth, swinging to a different, happier beat than the one we hear in the trailer.

Ali Zafar, with a tilted neck and makeshift swag, drifts into the college campus. Jawed Sheikh, probably the dean of the institution, scolds the youth for their free-thinking mindset and insubordination. Marina Khan looks out the window in serious contemplation. Bilal Abbas Khan — one of the two leads of the film — sways into a pathway in what is probably his introductory slow-motion shot from a song.

The beat, somehow more dramatic now, continues ramping up — as if holding the viewer by the collar. There is a message here.

The camera pulls up on Sajal Aly, her look searing through the lens. In her hand is a script: Khel Khel Mein. A trashcan flames up behind her for dramatic effect.

“As you all know, the competition is in Dhaka. We should do a play on the 1971 Fall of Dhaka,” her voiceover states. “You mean, we go to Bangladesh and remind them how badly we lost?” Bilal’s character smirks in retort.

But the troupe — youngsters in search of truth — go to Bangladesh nonetheless (the film is shot entirely in Pakistan, by the way).

An overhead shot of a commercial airplane transitions the word Dhaka on the runway.

“We were in Pakistan — East Pakistan,” says an elderly Manzar Sehbai. He plays a Pakistani living in the slums we see from an aerial shot.

Then there are the stock representations: a hoodlum-ish gang from India led by a burly, muscle-less Naveed Raza, sneers and leers. An actress playing a Bangladeshi, intimidates. A Bangladeshi man in uniform ridicules. Our youngsters, dressed in black, put on a show. The background glows red. One of the actors theatrically smacks red powder over his face.

Despite the intense theatricality of the enterprise, this is a story of love, maturity, understanding and forgiveness.

“You’ll find equal love, if you search both hearts…,” interjects Bilal’s voice.

“Whoever has made the mistake. Let’s apologise to each other,” says Sajal’s.

There was much to take in, and I wanted to ask for a repeat, but the trailer was due to air in two days’ time. If you’ve tuned into any ARY channel in the last week — the film’s media partner — then the trailer is hard to miss.

KKM is distributed by Eveready Pictures, who also have Nabeel’s next film Quaid-i-Azam Zindabad (QAZ) lined up for release in late December.

“It only makes sense to release QAZ on the Quaid’s birthday,” affirms Nabeel, “Just as it makes sense to release KKM this year.”

The year 2021 marks the 50th year of the ‘Fall of Dhaka’. Releasing the film on the 51st year didn’t make sense — ergo the hurried release, explains Fizza Ali Meerza, KKM’s producer.

“As a woman, I can say that no delivery should take more than nine months,” she quips.

The film was shot in February of this year, and had a schedule of 50 days.

The idea of making KKM hit them around the time we sat down last October, they tell me. At that moment in time, they were gearing up for QAZ’s trailer launch (an exclusive first-look of the film was published earlier by Icon).

“Even back then, we planned on releasing QAZ in late December. It was either that or August 14,” Nabeel says, his attention divided between his phone and the laptop.

With barely two weeks in hand to get the promotions rolling — the film releases on November 19 — manic energy pumps through every minute of their enterprise. Actors are being lined up for promotions (that’s one of the hardest jobs of PR), campaign designs are getting final touch-ups, and goodie-bag deliveries for the trailer’s launch the day after are becoming a pain in the neck. But, then again, this isn’t Nabeel and Fizza’s first rodeo.

By experience, I know they don’t talk about their stories, and given the circumstances, we don’t talk about the obvious or the redundant.

Another smaller film, also titled Khel Khel Mein — an Enid Blyton/ Secret Seven-type story — had already secured and registered the title beforehand. As per this writer’s information, the other party has since chosen to simplify their film as Khel. It is a small sacrifice for the resurgence, survival and sustainability of cinema in Pakistan, a source affirmed earlier.

Actually, there is a lot of that going around.

The combination of ARY and Eveready — the former, a major film distributor in its own right that has rarely aligned with other distributors (there has been an exception or two), the latter Pakistan’s oldest and most respected film distribution and production company — signals a positive shift in the paradigm.

With audiences slowly getting their heads around the inflated cost of movie-watching in cinemas — the going rate is 800 rupees a ticket — they need a lot of convincing and enticement to dig deep into their wallets and/or purses.

Fortunately, Nabeel and Fizza are bankable names in the film business. Their filmography includes Na Maloom Afraad, Na Maloom Afraad 2, Actor in Law and Load Wedding. Most of these titles are recognised by the common man.

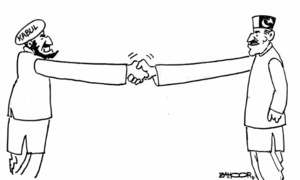

Although the Filmwala brand (their production company) is known for their topical, socio-political, message-laden commercial stories, they’re pushing the envelope hard by making a film about the relationship between Pakistan and Bangladesh.

“My best friend got married in Dhaka, and I couldn’t attend because I was shooting Load Wedding then. So, I promised to visit her. Little did she — or I — know that it wasn’t as easy. The first thing I realised was that Bangladesh’s visa is one of the toughest to get,” Fizza elaborates. “That intrigued us. I thought we had moved on, but we haven’t, because there is no interaction between the countries.”

Hailing from a generation that never saw or understood the effects of 1971’s East-West Pakistan separation, Nabeel and Fizza — like most of us — relied on secondhand information.

“Sometimes things are said so many times that you start to believe that they are right, and you don’t do your research. Eventually, you start to become a part of the same narrative,” she elaborates.

“When we were thinking of writing something around the idea, we hit upon the question: what actually is the problem?”

There were plenty.

During research, they found that every fourth or fifth person they met had a connection with Bangladesh. Some were descendants of East Pakistanis, others had grandparents who had been prisoners of war, and some had immigrated because the Pakistani rupee was a stronger currency.

Then there was the question of recognition, rights and nationality: after the secession of Bangladesh, should second, third and fourth generation descendants still be labeled as immigrants?

“Are they Bengali nationals or Pakistani nationals? It’s the same in both countries,” she says.

“There are between 500,000 to 600,000 people of Pakistani origin living in the slum-like area called Geneva Camp,” Nabeel interjects. The conditions there are deplorable, he adds.

“People make films about Pakistan and India, but somehow this topic is never looked at,” he says. “It’s almost as if it’s taboo.”

Is KKM about accepting faults, I ask?

In a way, yes, Fizza answers.

“Mistakes have been made on both sides, there is no doubt about that — and accepting this doesn’t make one lesser than the other. That’s the solution to any problem.

“We made the film to better understand the problems and the divide, but mostly we made it for today’s youth.”

Speaking of youth, we segue towards the actors. For KKM they decided to go for two of the most happening faces in television: Sajal Aly and Bilal Abbas Khan — each of them having precisely one Pakistani motion picture to their credit (the keyword is Pakistani; Sajal also starred in the Bollywood movie Mom with the late Sri Devi).

The actors fit in quite well within the mould of the story. Bilal is a natural when it comes to playing youngsters and Sajal is well-known for her thematically intense choice in scripts.

But getting them lined up for an interview is a hassle. Bilal was out of Karachi and Sajal wouldn’t be free until the day of the trailer’s launch.

Still, Bilal made time and we spoke at 2am in the morning two days after my meeting with Nabeel and Fizza. He had just gotten home after a delayed flight.

“I didn’t even take a shower yet,” he tells me. “I would have dozed off if I did,” he laughs.

The characters are quite straightforward, and it makes sense to have them that way, I learn, because the topic and its underlying themes do the heavy-lifting.

“I play Saad, a simple university-going student who wants to be an actor. He is kind of like me,” Bilal cheerfully adds.

But then again, hasn’t Bilal been playing these very stereotypical straightforward and realistic characters time and again, I ask?

He tells me that he is quite picky and choosy with projects, detailing exactly how his other roles differ.

So, what does he bring to the table this time, I ask?

“A lot of food,” he laughs. “Saad is such a simple character that excessive homework would ruin him.”

Another day later at the trailer launch, one had no choice but to concur. The characters were simple, but the story wasn’t. Revealing details about either character led to the danger of spoilers unintentionally slipping out during conversations.

“I’ve chosen the film because of Nabeel and Fizza,” says Sajal, with whom I finally sit down for five minutes. It’s the honest truth — one she has reiterated throughout the event.

“I have been lucky to always get roles that have substance to them. If truth be told, I’m blessed. Whenever I feel that I have to take some time off, I get a project that I can’t say no to. I do them, maybe because I feel it’s my responsibility to be part of something substantial.

“But I still would say I’m lucky. And when you do things often enough, you do become picky,” she adds with a sweet grin.

As serious as KKM appears to be from the trailer, and as little information is shared by the cast, it still appears to be a full-blown commercial film, brimming with zany energy. Big sets, simple characters, a strong message, Khel Khel Mein might just be the right film for Pakistani cinemas to make a grand comeback with.

Published in Dawn, ICON, November 14th, 2021