THERE is little doubt that the world is in the throes of one of its most unsettled periods. The coronavirus pandemic has only added to uncertainty in international politics at a time when the world is in flux — with global power shifting, the stand-off between the world’s two superpowers continuing and a rules-based order eroding as big powers qualify their support to multilateralism.

How does one describe this era? The latest Strategic Survey by the London-based International Institute of Strategic Studies, among the best annual reviews of geopolitics, grapples with this question but rejects the idea that a single phrase or typology can capture it. It refers to several descriptions including “return to great power politics”, “A G2 world”, “The Asian century” but finds that none of them work to reflect a multidimensional reality. Diverse issues have strategic impact, it says.

Nevertheless, even without invoking a single overarching phrase to depict present-day geopolitics certain key features of the strategic environment stand out. They include fierce competition between the two global powers, weakening commitment to multilateralism amid growing multipolarity, intensification of tech wars, retreat of globalisation, renewal of regional conflicts, rise of hyper-nationalism as well as of authoritarian, populist leaders.

Read more: Turning from Afghanistan, US sets focus on China

The policy and intellectual debate about the international landscape that has to be negotiated today is enriched by several new books. One of them is the recently published World Politics Since 1989 by the Belgian scholar, Jonathan Holslag. But this no simple rundown of recent global events. It is an intelligent guide to understanding the shifts in international politics and the varied challenges of our times. It deals with key turning points or moments of change in order to encourage deeper thinking about the underlying political, economic and social factors. Holslag sees world politics as a ‘grey zone’, a web of interrelated trends and argues that the internal dynamics of states are just as important in shaping international affairs.

The strategic environment is marked by instability and uncertainties of a fractured world.

The book starts with the end of the Cold War and the advent of globalisation, which held out a promising era of peace, cooperation and prosperity for all. The author then fast forwards to 2019 when the pendulum swung back as trends of de-globalisation, extreme nationalism, xenophobia and authoritarianism became dominant. That was also when the world saw Brexit and Trump’s narrow defeat in the US election. Interstate tensions and territorial conflicts erupted while the West fragmented and failed to lead. He maintains that the three post-Cold War decades, following a ‘shaky’ unipolar moment, was a missed opportunity and produced a crisis of politics, diplomacy and even civilisation. And when the coronavirus pandemic overwhelmed the world “instead of joining forces the major powers unleashed a propaganda war” and WHO became a battleground between the US and China.

Holslag seeks answers for the resurgence of nationalism and turbulence and finds them in a combination of factors. He focuses on eight themes in the book. He identifies them as: limits of globalisation due to its unequal impact, fundamental global power shift, changing nature of power, the ‘decadence trap’ (when reckless consumerism in the West triumphed over civic duty and entrepreneurship), Western hubris that produced half-hearted engagement, “remote-control interventions” and bombing countries “into obedience”, the West’s unintended fuelling of authoritarianism, reaction against the West’s coercive. approach that yielded the politics of strife rather than cooperation, and a surfeit of learning undermined by a deficit of actions.

A thoughtful critique of Western policies runs throughout the book’s 12 chapters but is particularly telling in the one on foreign policy. The author explains that the West’s own goals — “inconsistent policies” — were responsible for its weakening and challenges to its leadership. Among these was the failure to learn lessons from successive economic crises. Even after the West’s apparent, though superficial, triumph in the Cold War it demonstrated a reluctance to lead. The rhetoric was of confidence, but in deeds there was reluctance. He shows how the policy contradiction between asserting global leadership and ‘remote-control engagement’ undermined Western goals. Reliance on sanctions to make states compliant produced this: “By the late 1990s over half of the world’s population was subject to coercive economic measures”, mostly imposed by the US. And “the foreign policy discourse was interventionist and moralising”.

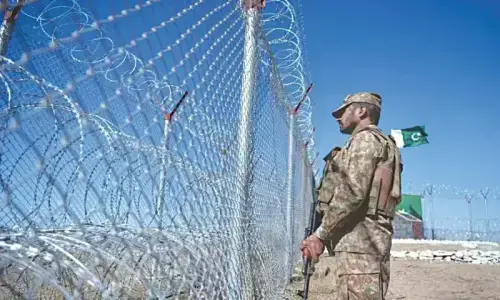

Post-9/11, he writes, Western especially US foreign policy became “a curious combination of a dysfunctional crusade against terrorism and an ineffective campaign to advance globalization”. The recklessness of the unilateralist American approach was evidenced in the two wars in Afghanistan and Iraq that overstretched it as well as its partners. Regime change was sought and the consequence of what Holslag calls mission creep, hubris and miscalculation was that it left the US and the West diminished and their global reputation damaged. He also refers here to Pakistan’s military that saw “Washington as arrogant and only interested in saving its face”.

Read more: Longest war: Were America’s two decades in Afghanistan worth it?

Resentment against the West also intensified, according to the author, by the refusal to reform the international financial architecture despite its eroding economic power. And while the West weakened, China’s rise continued apace. With its rapid growth it also linked much of Asia to its economy and supply chain. Holslag’s analysis of the Chinese economic miracle is both insightful and instructive. But his discussion of why the world got to where it is today is even more compelling. He argues that after the 2008 financial crisis, stability never revived in the West which lost its position as the global economic centre. Political trust in governments plunged. Democracy weakened. All of this contributed to the fragility of peace in the world.

Read more: The Chinese economic miracle

Holslag sees three changes that have defined the world order, the rise of China, decline of optimism in the Global South as regional powers like India and Brazil failed to strengthen their economies and what he calls the return of “hard hedging”. By the latter he means regional powers playing to both camps — US and China — to avoid taking sides in order to maximise their options and autonomy. As a result, the world today is “more fragmented and turbulent”. This is a must-read book for students but even more so for policymakers, business leaders and all those interested in what drives geopolitics today.

The writer is a former ambassador to the US, UK & UN.

Published in Dawn, November 15th, 2021