THE bitter truth has been staring this nation in the face for years. Religious violence spawned by allegations of blasphemy has taken on a life of its own, destroying the fabric of society slowly but surely. And yet it is only now, with the gruesome murder of Sri Lankan national Priyantha Kumara Diyawadanage at the hands of a mob in Sialkot, that the leadership appears to have realised this.

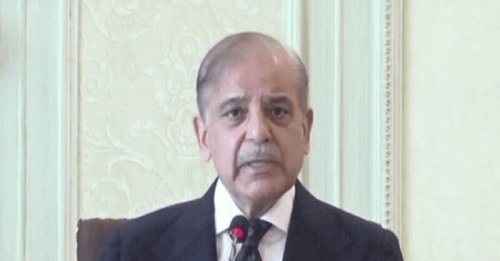

Addressing a condolence reference for the slain man at the PM Office, Imran Khan vowed that no one will be allowed to kill another in the name of religion and perpetrators of religiously motivated violence would be strictly punished. He went on to say that such was the climate of fear that those accused of blasphemy rotted in jail with no one even willing to investigate what had actually happened. “Everyone is afraid of it. In fact, lawyers do not come forward and judges also refuse to hear the cases.” That, he added, was all the more reason to laud the actions of Malik Adnan, Mr Diyawadanage’s colleague who tried in vain to save him from the mob.

Read: Lessons from the Sialkot tragedy

Mr Khan’s observations are correct, but we have for too long travelled down a path where elements of the state themselves rationalise religious violence, or at the very least condone it, as an appropriate response to certain ‘provocations’. To gauge how monumental any effort at reform is, one need only recall that there stands in Punjab a well-frequented shrine to the man who murdered former governor Salmaan Taseer because he believed him to be guilty of blasphemy.

Moreover, the reaction of the ruling elite and the religious lobby to Mr Diyawadanage’s lynching is questionable. Several of the clerics vociferous in their condemnation of the murder as “inhumane and un-Islamic” have been the driving force behind the blasphemy campaign across the country that has been the cause of untold misery to thousands. Some, like Junaid Hafeez — a textbook case that illustrates what happens to blasphemy accused in the criminal justice system — languish for years behind bars.

Does the pain and anguish of these Pakistanis not register with the civilian and military leadership, members of which have been complicit in using the issue of blasphemy to achieve political ends and thereby fanned the fires of hate? There must be no tolerance for religious violence, no averting of the eyes when some communities or individuals are targeted. None of us are safe, until all of us are safe.

Judging by appearances, the lynching in Sialkot seems to be a watershed moment. Whether it proves a catalyst for real change is as yet unknown. Sadly, history tells us that this nation has a very limited capacity for self-reflection, let alone taking the difficult steps that would be needed to root out what is no less than a cancer of the soul.

Published in Dawn, December 9th, 2021