"I was five in 1965 when, I remember, Daddy asking my mother Jeanne if she would like to come with him to India,” Lesley Ann Middlecoat, the only child of Wing Commander Mervyn Leslie Middlecoat of the Pakistan Air Force (PAF), begins her story with a prominent memory. The depth in her big wide-set eyes, so much like her father’s, is infinite.

“Mother was immediately excited. She got dressed up, dabbed on some nice perfume and we got into our Volkswagen Beetle, only to arrive at Khem Karan, a territory captured from India by Pakistan after a terrible tank battle. It was a terrible place. It reeked of death.”

Lesley recalls in vivid detail: “There were dead animals with inflated stomachs lying around. There were dead people inside tanks. Mother was horrified. She refused to get out of the car but Daddy got out. I also reached out, my little arms extended for him to pick me up. He lifted me out of the car, despite my mother’s protests, and carried me in his arms to the nearest tank.

“It had a big hole on one side through which we could see two men seated inside. I tried to touch the arm of one, which just disintegrated. It turned into powder. Ash. Daddy was annoyed at me for doing that but I had questions. I asked him if they were bad men. Because in my head there were only two kinds of people — good and bad. He looked at me and said, ‘Les, that’s someone’s daddy.’

“I saw a tin case lying in front of one of the two men. It had his glasses. I asked my father if I could have it. Daddy nodded and I took it. It remained with me till December 12, 1971.”

That is the day Lesley’s father was himself declared missing in action in another war.

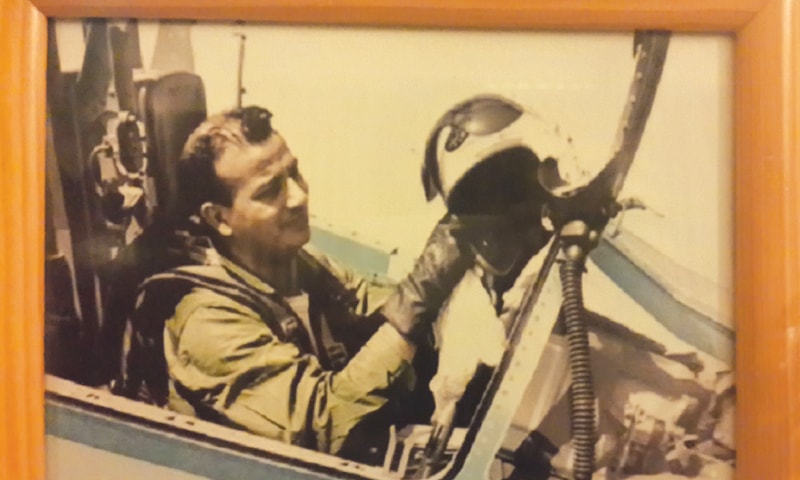

Exactly 50 years to the day, PAF fighter pilot Wing Commander Mervyn Leslie Middlecoat was declared missing in action. His daughter remembers his legacy as not only of valour and patriotism but of a father who taught his little girl invaluable life lessons

“I was now 11. Daddy would call us after every mission. He called us on December 10, he called us on December 11. He asked Mother to come to Karachi because we were in Peshawar then. She was about to ask him, the next time he called, to make arrangements for us to come to Karachi. But there was no call on the third day. And we knew. Another child’s daddy was gone. That day I took out that tin case with the glasses and buried it in our lawn.”

Lesley’s childhood memories are aflood with little things, significant things, snippets, conversations, chiding — a crash course on life that she has held on to all these years.

One memory is from a wintry morning in the mid-1960s. A formation of two F-104 Starfighters, the pride of the PAF, roared across the mountainous landscape of the PAF firing range near Peshawar, hugging the terrain at a mere 100 feet. Lesley sat among the air show audience who watched in awe as the silver aircraft approaching the stands suddenly went silent, followed by a deafening boom, a few seconds later, as the aircraft crossed the sound barrier, shaking the audience out of their seats.

They turned around at a low altitude and came past the stands again, as the audience held their breath expecting another boom. But this time, the lead aircraft rolled upside down while still in formation and then performed a loop to come back past the stands. The pilot, then Squadron Leader Mervyn Middlecoat, commanding the elite No. 9 Squadron, then performed a dazzling display of low-level aerobatics, ending with his signature vertical rolling climb till he disappeared from sight into the blue sky.

“Of all the aircrafts that he loved to fly, the F-104 was Daddy’s absolute favourite. To me it looked like a rocket,” says Lesley.

The F-104 inside the PAF Museum is, in fact, the very plane that Middlecoat would fly. By then a Wing Commander, he was on a training assignment with the Royal Jordanian Air Force when war broke out on December 3, 1971. He requested for his return, to report for duty in Karachi and volunteered for a mission to attack the Indian air base at Jamnagar. He flew his first mission the very day of his return on December 10. After, he called his family at maghrib. They were allowed three-minute phone calls once a day. He flew again the next day, and called them again.

“I told him I was praying for him and his squadron,” recalls Lesley. “I wanted him to return. I told him this over the phone and he said to me to pray for Pakistan.”

The third day, he didn’t call on his regular time. When Jeanne called up Masroor Base she was informed that his aircraft had been shot down somewhere over the Indian Ocean.

“Hope is intoxicating,” Lesley says. “It has a life of its own. It keeps you going. It kept my mother and me going. She would say to me ‘Les, if there is any possibility of coming back, he would come back.’”

For years, Middlecoat’s wife and daughter held on to the hope that he might come back. “My mother was a volunteer for the Red Cross,” explains Lesley. “We would go together to the Wagah border whenever there were prisoners of war [POWs] coming back. There were 83,000 POWs in 1971. There used to be a list and Daddy’s name would not be on it. Still we would go. Because what if he had had a head injury and had forgotten his name? Also, the Indians would not always give complete or correct names of the POWs.

“I was studying in Murree then. Mother would call from Peshawar, telling me to get ready. She would drive all the way from there to Murree, pick me up and then drive all the way to Lahore. Each time I was excited. There was fresh hope. We would sit there watching the uncles coming back. Some even looked like Daddy but…”

Daddy is the only PAF pilot who got the declaration in two wars. Between the wars, he also got the highest peacetime award, a Sitara-i-Basalat. He is the only person to have been awarded three gallantry awards in Pakistan’s history. But he never got around to receiving the Sitara-i-Basalat in person.”

The daughter remembers her father as a pleasant, uncomplicated person. “He would laugh easily. He would laugh so much that there would be tears forming in his eyes. Being an only child, I got the undivided attention of both my parents. But I was closer to him. He would talk to me and I absorbed every word he said. He would make us stand up for the national anthem. I was taught to march before I could run. I was taught how to salute.

“Daddy was decorated with the military award of Sitara-i-Jurat in 1965 and he was awarded another of the same posthumously for 1971. He is the only PAF pilot who got the declaration in two wars. Between the wars, he also got the highest peacetime award, a Sitara-i-Basalat. He is the only person to have been awarded three gallantry awards in Pakistan’s history. But he never got around to receiving the Sitara-i-Basalat in person. He didn’t care for honours and awards. Being a fighter pilot for the PAF was the greatest honour for him. ‘Imagine being paid to do something one is willing to do for free,’ he would say to my mother,” Lesley says.

His name is printed right at the very top of the list of martyred fighter pilots in 1971 at the PAF Museum gallery in Karachi. “Because he is the senior-most of all fighter pilots who laid down their lives ever for the land,” says the daughter.

“He named me after himself, something that my mother never forgave him for. He had been sitting outside the delivery room soon after my arrival into the world. Fathers were not welcome in the delivery room in those days. While filling out the hospital forms, he gave me his middle name. And when my mother came to, she felt cheated. She wanted her name also somewhere in there,” the deep eyes are smiling now. It is a happy memory, one that the daughter had been told often while growing up.

Lesley learnt the word ‘martyr’ before she could understand its meaning. “I was learning counting. I counted aircrafts when they flew off on missions. I counted them when they returned. Sometimes they wouldn’t add up on their return. I remember every uncle we lost in the 1965 war. We were at Sargodha Base then. There was Uncle ‘Butch’ Ahmed, Daddy’s best friend and the senior-most pilot whom we lost in 1965, there was Uncle Sarfaraz Rafiqui, there was ‘Pa’ Munir.”

Those eyes are smiling again at the mention of Pa Munir. Lesley does not remember his full name, only what everyone lovingly referred to him as. “Pa means big brother in Punjabi. He was older than the others. But he loved to fly and hated having a desk job so they let him fly even though he stuttered. By the time he could complete a sentence asking permission for takeoff, they would have already given it to him,” she laughs through the tears.

“The night he [Pa Munir] went missing in 1965, I remember all the mothers gathered at his place, crying, as the children gathered in the lawn to play. He was a ‘shaheed’ [martyr]. We knew being shaheed was a great honour. We just didn’t know how final it was, that it meant you were not coming back. The same scenes I remember after Uncle Sarfaraz Rafiqui and all the others whom we lost in that war. We talk about them often. But we rarely speak about our losses of 1971. Unlike 1965, 1971 is a sore topic. Every year we celebrate 1965 but 1971 broke our hearts, our spirits.

“I am Christian but I used to get a new Eid jorra and pretty bangles, etc., every year. Then one day I asked why we didn’t get visitors too on Eid. Daddy took me out and asked me to point to any house. I pointed to homes we had not been to before and he accompanied me there as he told the folks there that his daughter was feeling lonely on Eid. We were welcomed wholeheartedly at any house, at any air base, on Eid and that’s how he taught me that the PAF was my family. I still feel that way.

“I remember all his mates making sure that I was alright after he was gone. They were all very kind to me. One of them, Khaqan Abbasi Uncle, who taught Daddy how to fly the F-86 Saber and who years later was instructed by Daddy how to fly the F-104 Starfighter, would take me for plane rides soon after Daddy’s shahadat [martyrdom]. When I’d ask why his children were not coming up with us, he would dismiss it by saying that their father was not a shaheed. But mine was. Therefore, I deserved special treatment.

“I remember saying to Daddy once that I hated India. All us children growing up at air bases used to say such things. But he chided me about it. He said, ‘In life you do things out of love. Love is powerful. Hating my enemy won’t help me but loving my country will. I want my country to prosper.’ And I understood.”

After her mother’s passing in 2011, Lesley found the Indian pilot who had shot her father’s plane down. There is no hate, no anger in her heart. But there is understanding.

“When Daddy went MIA [Missing In Action], we didn’t know what could have happened to him though we thought about it often,” Lesley says. “We only had the name of the Indian pilot who had shot his plane down, Flight Lt Bharat Bhushan Soni.”

“One day, I saw a message on Facebook from someone named Arjun asking me if I was Wing Commander Middlecoat’s daughter. From the name, I could tell that he was Indian. I didn’t reply. But he messaged again saying that he is the son of an Indian Air Force officer and he knew about my father, that he had found me on his friend Ishrat Aurangzeb’s friends’ list.

“Ishrat is Gen Ayub Khan’s granddaughter. She studied with me at the Convent school in Murree. I reached out to her to ask about Arjun and she told me that he was harmless. His father was an air attaché based in Islamabad and he has lived here for four to five years. Ishrat said that, as a child, he was friends with her younger brothers.

“Getting to know Arjun slightly better, I asked him a favour, to put me in touch with Soni. Arjun then asked his own father to put the two of us in touch.

“I wrote a long letter to Soni, attaching photos of Daddy, my parents’ on their wedding day, of me with Daddy, asking for just a bit of his time to tell me about my father’s end. He messaged back saying that he had read my letter several times. He requested some time as he said he felt choked with emotion, overwhelmed. He had never thought that he would be corresponding with Wing Commander Middlecoat’s daughter, who would address him so respectfully.

“Soni told me that he and his squadron commander had come to Jamnagar from another air base in their MiGs as the Indian aircraft at Jamnagar were unable to take off while under attack from the Pakistani F-104s. These two Indian pilots had come to intercept the Pakistani aircraft. They took their positions on both sides of a lone F-104.

“The F-104 has a big turning radius, which they knew about. They didn’t allow it to turn as they fired at it constantly. One rocket hit the aircraft’s tail and the pilot ejected. Soni requested to take a round to see where he was going to land but was ordered to return to base as they had the coordinates for the Indian Navy to pick him up. But by the time the Indian Navy reached there, it was too late. There was no sign of the Pakistani pilot. It is said that there is this five-mile radius of shark-infested waters in the Indian Ocean and Daddy had landed right in the middle of it,” she sighs.

After giving her the last piece to complete the picture of her father’s memory, Soni and Lesley continued their correspondence. They have formed a unique friendship over the years.

“He tells me now that he shares a bond with me that he can’t even say he shares with his own children. I also understand that he was doing his duty just like my father was doing his. Daddy used to tell me that when flying, he only thought about the altitude of his plane and how much he loves his country.”

This year, Soni is being honoured in India along with their other military heroes to celebrate India’s victory of 50 years ago.

Lesley herself is a mature woman now. She has a fine career in human resources. Sometime ago she was also offered to go abroad for work for two years. “I was happy. But when I told my mother about it, she wasn’t. She said that if I left, I may not come back. ‘If this country was good enough for your father to die for, it is good enough for you to live in’, she said to me. The next morning I thanked my company for the offer but declined it,” she says.

The writer is a member of staff.

She tweets @HasanShazia

Published in Dawn, EOS, December 12th, 2021