‘The road to hell is paved with good intentions.’

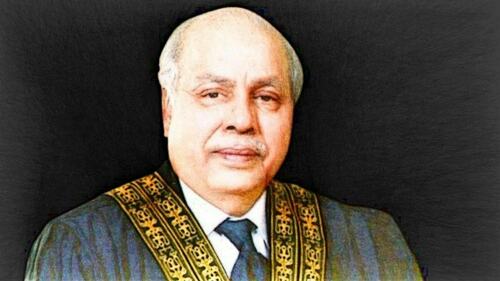

WHEN justice Gulzar Ahmed was appointed chief justice of Pakistan in December 2019, there was room for optimism for two reasons. Firstly, Justice Gulzar was a humble, decent and non-controversial personality with a burning desire to do public good. Secondly, unlike his numerous post-2013 predecessors, he had the longest tenure as CJP of just over two years, which could enable him to patiently strategise his tenure. But judging by the negative public reaction to his tenure, the question arises as to how and why things went wrong. It is imperative to make this assessment, otherwise courts are bound to repeat similar mistakes, with further disastrous consequences.

Read more: Chief Justice Gulzar Ahmed: Master planner or yet another populist judge?

The good: With all the confusion and disasters, it would be unfair not to highlight the positive contributions made during the tenure of CJP Gulzar. Firstly, as rightly pointed out by CJP Umar Ata Bandial, the historic appointment of the first female judge of the Supreme Court, Justice Ayesha A. Malik, was not possible without “the resolve of Justice Gulzar … to bring women on the [Supreme] Court”.

The previous CJP’s tenure was symbolised by confusion and ineffectiveness because of the lack of judicial vision.

Secondly, the historic quashing of the presidential reference against Justice Qazi Faez Isa by the Supreme Court and its consequential dismissal by the Supreme Judicial Council, headed by CJP Gulzar, was also possible because the latter played a non-interventionist and non-conspiratorial role during the pendency of the reference.

Thirdly, despite his numerous disastrous orders and arbitrary judicial approach, CJP Gulzar has restored more parks in Karachi than any other judge in Pakistan’s history.

Fourthly, the flourishing of dissent both at the Supreme Court, as well as in the judicial commission for the appointment of judges, was a consequence of not only his weakness as CJP but also because of his non-dominating personality.

Fifthly, CJP Gulzar’s special attentiveness to minority rights continued and developed the growing tradition of the Supreme Court (ie of Justice Shafi-ur-Rahman, Justice Tassaduq Jillani, Justice Saqib Nisar and Justice Asif Khosa) of positive discrimination in favour of minority rights.

Read more: Fawad lauds retiring CJP Ahmed for 'historic stand on minority rights, independent judgments'

The confused: CJP Gulzar’s tenure was generally symbolised by confusion and ineffectiveness because of the lack of judicial vision, indifference to understanding the causes of judicial problems, and resultantly, no strategic plan to tackle any substantive judicial problem. CJP Gulzar acted on instinct, gave judicial sermons and dealt with judicial problems on an ad hoc basis. Four examples elaborate this point.

First: the judicial proceedings regarding the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the country and its citizens. Except for judicial sermons and vague, ineffective orders, can anyone recall any good coming out of these proceedings? They were an exercise in futility because the court failed to seriously reflect on what it wanted to achieve and what it could achieve through judicial orders.

Second: the summoning of the prime minister in the 2014 Peshawar Army School tragedy. Did the court achieve anything except an exercise in judicial showmanship, temporarily deflecting the anger of parents without passing any effective orders regarding the state’s criminal negligence?

Third: CJP Gulzar’s judgement in Reference No.1 of 2020 regarding the confidentiality of the Senate election. The oxymoronic irrelevance of the declaration that the Senate vote is both confidential as well as not absolutely confidential became obvious as the Election Commission, in effect, ignored it.

Fourth: CJP Gulzar’s judgement on the Sindh Local Government Act, 2013, and the enforcement of Article 140A of the Constitution. An examination of para 46 of this judgement shows that it is mainly composed of judicial sermons and directions to the Sindh government to take vague measures and enact vague amendments, without specifying what the enforcement of such measures would entail as it is left to the Sindh government’s discretion. This judgement would be as ineffective as the flawed Supreme Court judgement in the Imrana Tiwana case of 2015, which sadly overturned the brilliant Lahore High Court judgement of Justice Mansoor Ali Shah regarding local government powers in Punjab. In short, CJP Gulzar’s jurisprudence can aptly be summarised in the words of Shakespeare as being “full of sound and fury, signifying nothing”.

The disastrous: Dealing with jurisprudential dissonance would have been bearable but for the numerous disastrous orders passed in the Naimatullah Khan cases or Karachi encroachment cases. Leaving aside clear-cut cases of encroachment of parkland with minimum human dispossession, demolition and dispossession orders in other cases led to constitutional and human rights violations.

Firstly, an examination of the various orders shows that except for being lectures on urban planning and morality, such orders were devoid of jurisprudential worth. It is quite amazing that all these proceedings were conducted under Article 184(3) of the Constitution but none of these orders tell us anything about how, why and when this jurisdiction should be exercised.

Secondly, CJP Umar Ata Bandial captures the tragedy by politely noting: “These actions although rooted in law, received a mixed reaction because the orders failed to identify and punish the actual perpetrators and the officials responsible.” Thousands upon thousands of people lost their homes, jobs, businesses, property, and sense of respect and peace due to orders which were disproportionate, hasty, without proper due process, without reflection and without exploring alternative solutions in pursuance of favourite projects like the Karachi Circular Railway and the Empress Market (emptied of human life) and an ill-informed vision of a lost, puritanical Karachi.

Thirdly, the order to raze a Karachi mosque led to defiance and explicit threats to CJP Gulzar from religious leaders. CJP Gulzar kept silent on this. This was seen as the court’s inability to have its orders implemented against certain groups.

Judges with good intentions, who are emotionally over-invested in specific favourite issues but who do not reflect intellectually on their orders and their role as judges of the Supreme Court can cause damage to the rule of law and human rights. Therefore, the highest point of CJP Gulzar’s judicial achievement was the demolishment of the high-rise Nasla Towers building. Destruction became his judicial hallmark.

The writer is a lawyer.

Published in Dawn, March 23rd, 2022