Sara Suleri Goodyear died peacefully at home on Sunday, March 20, 2022 of pulmonary failure. She was 68 years old. She was my friend.

Sara disliked being called exotic; except that she was. Hugely so. Dazzling, elegant, glamorous, charmingly imperious, impossibly intelligent. And most of all, fabulously, hilariously, screamingly funny.

As an author, Sara was adored, respected, admired and even worshipped. In 1989, Meatless Days burst on the scene with the same explosive energy that Quratulain Hyder had sparked with her magnum opus, Aag Ka Darya [River of Fire]. Both women were uncannily similar, inspiring a parody that began thus:

Qurratulain hain adab mein dakheel

Jaisay mulk-i-Arab mein Israel

[Qurratulain has occupied literature

The way Israel has Arab land]

My friend Professor Tahira Naqvi wrote in her condolence note: “I don’t think there is a book cover that has ever made a place in popular consciousness as that of Meatless Days. I can’t remember a book from my early days here that had as much of an impact as that brilliantly written memoir.”

As recently as this January, Sharon Cameron — a beloved friend and an exacting professor of English — read Meatless Days and had this to say: “I so admire the complex way SS weaves together family and Pakistani history and the nuanced way in which the narrative moves in and out, and then back around and at an angle through subjects newly given contour and life. SS is a very gifted writer.”

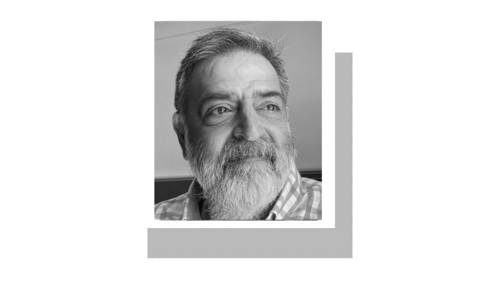

Sara Suleri Goodyear (1953-2022) was perhaps best known for her memoir Meatless Days, but a close friend and collaborator remembers her as so much more than a professor and writer

I read this to Sara over the telephone. Pleased, she remarked that the only other person who understood her “narrative weaving” was her friend and author David Lelyveld who, upon reading Meatless Days, exclaimed: “It moves like a ghazal!”

To this, Sharon responded: “The ghazal is an apt image… she has a rare capacity — as much philosophical as historical, as much intuitive as conceptual — to see the coils, repetitions and undoings of sequence such that any event, person or phenomenon can’t be located in a single or unified time and place, but recurs and recurs.”

The book didn’t just impress readers, it often had a strange effect on them. Some identified with her experiences at a deeply personal level, almost claiming ownership of them. In 2004, the great Indian filmmaker Shyam Benegal and his wife Nira arrived in town and my friend Anita Patil (actor Smita Patil’s sister) took us out to dinner.

We were barely seated when the incredibly sophisticated Nira turned to me: “I was anxious to meet you, Azra. I’ve heard that you personally know the author I admire most, Sara Suleri. I’m dying to know everything you can tell me about her.”

Talking about a writer we mutually admired bonded Nira and me. When we compared notes on our favorite Suleri passage, we discovered one about Lahore that we both loved: “How many times have we driven down from Rawalpindi, fatigue in the marrow of our bones, to cross the full Ravi and then the empty Ravi riverbed, finally to see the great luminous minarets of the mosque rising in our vision like a gasp or a plea?

“Of course, nothing in the city quite lives up to the promise of such a welcome, so that somehow one is always expecting to find Lahore without quite locating it. I used to find it perverse myself, that aura of anticipation, until it occurred to me that the town has built itself upon the structural disappointment at the heart of pomp and circumstances, and since then I have loved to be disappointed by its streets. They wind absentmindedly between centuries, slapping an edifice of crude modernity against a mediaeval gate, forgetting and remembering beauty, in pockets of merciful respite.”

For a 2006 interview for Islamabad-based magazine Blue Chip, the questions were emailed to me — Sara was a total Luddite — and I transcribed her responses. “What do I miss about Pakistan? Well, the sound of Urdu spoken around me, the monsoons, the extended community that is signally absent from daily life in the United States. And even jokes about load shedding.”

She came to the US “in 1976, to do a PhD in English literature. At that time, my first love was the theatre. Had there been any viable, serious theatre for women in Lahore, I would never have left. But there wasn’t, so I came away, and chose to do the next best thing. The joke is that I had done my Masters at Punjab University [PU] before I arrived for a doctorate at Indiana University, and I was infinitely better prepared than my American peers. I whizzed through that degree with honours in three years! There’s something to be said for PU as it was in the old days.”

“First, I taught at William College … where I was barely older than my own students. Then I moved to Yale University in 1983 and have taught here ever since … my husband, Austin Goodyear … died of cancer on Aug 14 last year ... While one of his ancestors invented galvanised rubber, Austin had nothing to do with the tire company — he ran his own business, sailed a yacht he loved, and was perhaps the most energetic and engaged human being I have known. I miss him.”

She was a legend as a teacher. When my brother Abbas went for a job, the interviewer said she’d graduated from Yale and was fortunate to have had great professors who changed the way she thought about the world, and about her own life. “Most of all, a young professor named Sara Suleri.”

Once, I asked Sara why someone whose mind was as curious as hers did not gravitate towards the sciences. She said it was because she did not have good teachers. I asked if she’d had a good English teacher. She said yes; her mother. But she obsessed over my question. She felt that there are people with aptitudes in different fields than science who are nonetheless fascinated by it. When I explained any part of my own experimental work in oncology, she listened raptly.

After Meatless Days, Sara wrote Rhetoric of English India and Boys Will Be Boys to superlative acclaim. She and I co-authored Ghalib: Epistemologies of Elegance. One summer, after a full day of labour on the book, we relaxed on my porch. Sara felt particularly satisfied with our output that day.

The fading sun lit up her face, but I sensed an inner light emanating from her entire being. I grabbed my camera and took a hundred pictures, yet failed to portray even a fraction of her beauty. The picture here is from that series.

There was something ethereal about her that evening. We’d worked on the magnificent ghazal, ‘Woh firaaq aur woh visaal kahaan’ since early morning. I felt her face reflected the ‘Ranaaie-i-khayaal’ Ghalib imagined in this sher:

Thi woh ek shakhs ke tassavvur se

Ab woh ranaaie-i-khayaal kahan

[It was in imagining that one person

Now where is the grace of those lost thoughts]

Among her contemporaries, Sara greatly admired Harold Bloom. We asked him for a blurb. After reading the Ghalib book, he called me: “Azra, you say there are two authors, but there is only one voice.” He was absolutely correct. Sara and I had a great partnership. My job was to explain the sher in Urdu to her. We then consulted the 11 interpretations we had around us, debated the meaning, eventually settling upon the version we liked best.

Then Sara would say: “Now let me put this into difficult English.” I typed as perfectly formed sentences streamed out of her mouth effortlessly. I was astounded that Sara never edited her prose. She did the editing in her mind.

After four decades on the East Coast, Sara moved to Washington state to be close to her beloved sister Tillat across the border in Vancouver. I hadn’t seen her since the start of the pandemic, but we had regular phone conversations.

Covid isolation had done a number on her. In the last few months, she was in constant physical pain and could only speak for a few minutes at a time. She asked what if she stopped eating. I said she would not live beyond 10 days. She said she’d speak to Tillat about it. When she asked me to visit, I wasted no time.

Sara was excited to see me and my sister Sughra, her neighbour and friend in Boston. She was energised and talkative, feasting on crispy pakoras that she had Tillat fry. The afternoon we were to return, I was almost catatonic with grief; I knew I’d never see that cherished face again. Noticing my heartbreak, she mischievously sang, “Chup chup baithey ho zuroor koi baat hai” [You’re so silent, something must be the matter].

I could only respond with tears in my eyes. She rallied her secret resources to sit up, stared deep into my eyes and imperiously commanded: “Acha Az, now, no long faces around me please.”

That is the quintessential Sara we know and love. I returned home and read our Ghalib book as a way to feel close to her. This sher and Sara’s poignant words haunt me now as I write her obituary:

Kahoon kis se main ke kya hai shab-i-gham buri bala hai

Mujhe kya bura tha marna agar aik baar hota

[To whom can I even explain, the dark night of separation

What had I against a singular death if it did not recur plural times]

My friend is done with her anguish and rests in peace. She had the acutest powers of observation and could hear wordless voices. How I adored her, how I miss her. Long live Sara. Sara Zindabad.

Tread lightly, she is near

Under the snow,

Speak gently, she can hear

The daisies grow

— ‘Requiescat’, Oscar Wilde

The writer is professor of medicine and oncology at Columbia University, author of The First Cell and co-author, along with Sara Suleri Goodyear, of Ghalib: Epistemologies of Elegance.

She tweets @AzraRazaMD

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, EOS, April 3rd, 2022