Film criticism and scepticism go hand in hand, especially when it comes to Pakistani movies. So, imagine my disbelief when three of the five films set to premiere on Eid-ul-Fitr collectively destroy both the critic and the sceptic in me.

To clear the record before progressing: this writer has seen Chakkar, Ghabrana Nahin Hai and Parday Mein Rehnay Do (in alphabetical order here) days before their premieres.

Dum Mastam, the other big release of the season, is still being tweaked in the edit room, and couldn’t be seen by the time of this writing. That doesn’t mean that the film will fall short of expectations (fingers crossed).

The Syed Noor-directed Tere Baajre Di Raakhi, the fifth film in the Eid line-up, is a regional, Punjabi language production that may not get a countrywide release. Nevertheless, despite Icon’s attempt to include the film in this feature, no one from Tere Baajre Di Raakhi’s distribution, production or PR team came forward to preview the film for Icon or to provide details.

Five films are set to release this Eid. What should you go and watch? Icon provides the critic’s lowdown about three of them — Chakkar starring Neelum Muneer, Ahsan Khan and Yasir Nawaz, Ghabrana Nahin Hai starring Saba Qamar, Syed Jibran and Zahid Ahmed, and Parday Mein Rehnay Do starring Ali Rehman Khan and Hania Aamir

In any case, considering the products at hand, this is a wonderful time for Pakistani cinema. Brimming with commercial viability and mass appeal, backed by trusted and about-to-be-tested star power, what actually sets this Eid apart is the variety of genres the masses will get to see on the big screen: a whodunnit murder-mystery, a comedy about male infertility, a grand, romance-drama that turns out to be a heist story in disguise, and a colour-splashed musical about love and fame.

Rarely has Pakistani cinema exhibited such versatility and rarer still is the quality of narrative and production of these enterprises. Although competing Eid releases inevitably lead to accusations of foul play when it comes to distribution and exhibition plans, that would be a topic for another day. In this feature we review the merits and shortcomings of this Eid’s releases that, according to this writer, may just be instrumental in ushering in the post-Covid-19 revival of Pakistani cinema.

Listed in alphabetical order, here is what Icon thinks of the films this Eid…

Chakkar: A Diva, A Murder And a Pretzel of a Mystery

The Lowdown

A fast-paced, action-packed, murder-mystery that keeps its plot twisting till the end credits

Zara (Neelum Muneer) is a diva in every wicked sense of the word. She is fiery and snappy one moment, and petulant and unreasonable the next. She is a film star who is a graceless dancer (that’s the real actress’ shortcoming, I fear) but with whom prominent celebrities would still like to jiggy with in glitzy music numbers (the cameos in the song Chirrya that introduces Zara also has Sheheryar Munawar Siddiqui, Faysal Quraishi, Mohib Mirza and HSY; the lacklustre choreography is by Nigah Hussain).

When Chakkar starts, Zara is still a hot commodity as far as pretences go; in her real life, the walls are closing in fast. She is in debt, and her volatile nature and bad mouth are making enemies left right and centre.

Within the first 30 minutes of the film, she storms off from a shooting after shouting down her co-star and belittling a make-up artist (Shamoon Abbasi), and then leaves her manager (Rana Asif) in the middle of nowhere when he tells her to cool down for the sake of her career.

However, these people are just small fry. Her biggest nemesis equals her hotheadedness. Meet Kabir (Ahsan Khan) — the husband of Zara’s twin sister Mehreen (also Neelum). Kabir hates Zara’s guts like everyone else in the world, but he loves his wife; they even get to perform in the film’s only other, and far better, romantic song Dil Haaray, sung by Momina Mustehsen and Shafqat Amanat Ali, with music by Naveed Nashaad.

Mehreen, like most cine twins, is Zara’s mirror image. She is a meek, good-natured, stay-at-home-wife who loves her husband and is non-confrontational. Once, when the sisters meet, Zara tells Mehreen that she could have done far better than her grouchy husband; in fact, if Mehreen wanted to, she could have been a bigger celebrity than Zara. The conversation clues us in on the fact that Mehreen was a far better actress when the girls were in college.

It’s here that Zara proposes a switcheroo: hounded by the press because of the uproar she caused on a recent film production (the producer, who also hates her guts, is played by Mehmood Aslam), Zara wants time-out for some R&R. Zara will take Mehreen’s place and Mehreen will live the glam life of a movie star for the weekend.

And then murder happens. Kabir is framed for murder, and hot on his trail is a special investigative officer, Shehzad (Yasir Nawaz), touted as a ‘perfect detective’ by his superior (Javed Sheikh).

Chakkar is a brilliant change of pace for Yasir Nawaz, who co-writes, directs and produces the film (the last credit he shares with wife Nida Yasir). This is, by far, one of the most engaging mystery thrillers since Pakistani cinema entered its new wave in 2013. I’ve yet to see a thriller like this in the last 20 years in Pakistan — period.

Written by Yasir, Zeffer Imran and Syed Jibran (Jibran also stars in Ghabrana Nahin Hai, by the way), the film takes its title way too seriously; and given the genre, this is a good thing. The plot twists and turns, sometimes pulling off radical 180-degree spins while throwing deadweight and inconsequential characters in front of the audience to divert attention away from the real killer.

This is Yasir’s graduation as a filmmaker. He’s learned to adhere to the conventions of the genre without going overboard. Some of his directorial calls are quite astute. For example: the film does away with both songs within the first 40 minutes, and then ramps up the pace like a madman on the loose. The pace dips for about five minutes in the second-act, but then when you least expect it, the film does another spin.

The climax, which twists the plot at least twice, is a killer. In fact, it reminds one of the Denise Richards and Neve Campbell-starrer Wild Things — not that it steals anything from that film.

Chakkar is as close to perfection as the genre allows — especially considering the technical, budgetary and artistic limitations Pakistani productions have to contend with. The film has many pros and only a few cons when it comes to technicalities.

Let’s start with the editing: it’s snappy and well-suited to the genre. One assumes that, during Covid-19, editor Salman Tehzeeb has had time to fine tune and streamline some of the trickier aspects of the story (some double dealings will whirl the mind).

Saleem Daad’s cinematography is fine in bits and parts; the lacks, I assume, have to do with the use of lenses and lighting design in cramped locations (for example: Ahsan’s office scenes carry uncinematic High-Definition-ish sharpness). The action, when it happens, is blazingly fast and hardcore — in fact, the brawl between Ahsan and Yasir’s characters may yet be the most kinetic fisticuff one could expect from our cinema at the moment (the action is choreographed by Azam Bhatti).

Ahsan Khan looks and acts like a film star. As far as characterisations go, one would have loved to see Kabir explore the emotional connection with his wife some more.

Yasir fits into his role just fine, pulling off a much better performance in his own film this time round (he could have been much better in Wrong No. 2). Neelum is okay at times; not the most versatile of actresses, she does perform Zara with a delicious glee — but only in a few sequences.

However, by far the most enjoyable character in Chakkar is Ahmed Hasan. Ahmed — a young and handsome actor — goes full method acting here when he dons a very ugly wig, tacked-on silly moustaches and a baggy potbelly. With a strut in his walk, a raspy tone, and a heaving slack in his physicality, Ahmed transforms into Sir Buland Iqbal Cheema — an LLB who wants facts to be short and to the point; this very virtue, of course, is lost to him.

Given his get-up, Ahmed is a set-up as a comedy relief and, as the story unfolds, one expects Ahmed to pull off his guise at any moment, revealing a brand new player into the suspects line-up. That never happens.

Ahmed’s get-up may be cheap, but the character is a bona fide gem who turns out to be much more than the supporting character he appears to be. In a film preoccupied with twists and saturated with recognisable actors, sometimes in blink-and-miss roles (Adnan Shah Tipu, for example), Cheema is a beacon who just wants to understand what is happening. Akin to Cheema’s curiosity, unravelling the mystery might just be the best two hours you’ve spent watching a Pakistani film in cinemas this year.

Ghabrana Nahin Hai: Smart Alecks, Land-grabbers and an Unconventional Money Heist

The Lowdown

An experience worthy of the big screen… even at a 900-rupee ticket price

Zubaida — Zuby, as she’s called — has had enough. When her good-natured blue-collar dad’s property is misappropriated by a powerful land-grabbing don called Bhai Miyaan in Karachi, under whom works a corrupt yet violence-averse cop, Zuby will have to buck up and become a ‘mard’ (man) to get back her family’s land.

I’m sure woke feminists will have a problem with the constant allusion that a ‘mard’ is superior to an ‘aurat’; this, of course, is not the filmmakers’ assertion at all. In fact, the film is a pro-feminist tale of the highest order. If the premise doesn’t tell you that, then the dialogues pelted out in brute force by Saba Qamar, who plays Zuby, will make that clear.

Ghabrana Nahin Hai (GNH) — a far better title by the way — was once called Zubaida, Mard Bunn. While in theory one understands the gist of the original title, and its reference to a woman’s resolve in righting wrongs in a man’s world, in the context of the film however, we hardly see Zuby’s actions reflecting the spirit of the original title.

Zuby, who lives in Faisalabad, wants to be an actress. She has two million subscribers on TikTok, and an audition interview scheduled with a sleazebag “producer” in Karachi. When dad’s property is taken up by the city’s land-mafia, she tells dad and mom (Sohail Ahmed, Shazia Badar) to throw away their worries and that she, their only daughter, will take care of everything (i.e. Ghabrana Nahin Hai).

Off she goes, boarding a train to Karachi where lives Vicky (Syed Jibran — one of the many excellent aspects of GNH), Zuby’s love-struck cousin who wants to marry our girl ASAP. Zuby’s eyes and later her heart, however, locks on to the local SHO Sikandar (Zahid Ahmed, another of the film’s excellent assets).

Sikandar and his assistant-cum-cohort Aslam (Azfal Khan, aka Rambo, underutilised in the role) are working on a strict five-year get-rich-by-any-means timeline; they even have a red diary that keeps their focus tact sharp. Mostly Sikandar and Aslam’s schemes revolve around secreting the land-grabbing Bhai Miyaan’s dirty deeds. Sikandar himself is somewhat of a surrogate son to the don; the cop’s parents died during the violent ’90s, and the bad man raised the boy up for his own use.

The associations between Sikandar and Bhai Miyaan, and Vicky and Zuby, form the crux of this very entertaining romantic-heist movie.

Yes, you read that right: this is a heist movie, though that part of the tale comes very late into the film.

Written by Mohsin Ali (Wrong No. and Parday Mein Rehnay Do) and Saqib Khan — the latter also directs — GNH is a very well-written film that exhibits signs of multiple rewrites. The film has a streamlined, well-connected flow with few, if any, unnecessary segues.

Structured like a Bollywood feature film, this first film production and distribution by cinema owner Jamil Baig, and the fourth film by Hassan Zia (Wrong No., its sequel, Mehrunisa V Lub U), shows how a film can thrive if it has the right combination of expense, expertise and experience supplementing the director.

Now, when reviews come out, many will herald Saqib as a raw, sensible, wunderkind director — and they have all the right reasons to make that postulation — but what one needs to understand is that a director can only reach his or her potential if the production doesn’t take shortcuts to quality (shortcuts never work; they become very apparent on-screen).

Within moments of the first frame, one realises that GNH is a bona fide big screen motion picture, custom-built with just the right balance of technical and aesthetic pizzaz (the cinematography is by Asrad Khan of Bachanaa and PMRD fame).

The casting is pitch perfect: Zahid Ahmed, Syed Jibran, Nayyer Ejaz and Saleem Mairaj (who comes at the tail-end of the second act) are great value additions — each bringing their own A-game to the plot.

Bhai Miyaan, especially in the first-half, has an imposing, untouchable, reputation and extreme passive-aggressive anger (he has a penchant for chopping fingers off and feeding them to his dogs). His reclusive, egotistical nature and the build-up of his untouchability works to the film’s advantage.

While the film banks on Saba’s Zuby as the story’s spearhead, in reality her character is mostly the magnet that attracts these characters. Zuby’s actual actions, as I mentioned earlier, don’t amount to much because the boys end up doing all the work for her.

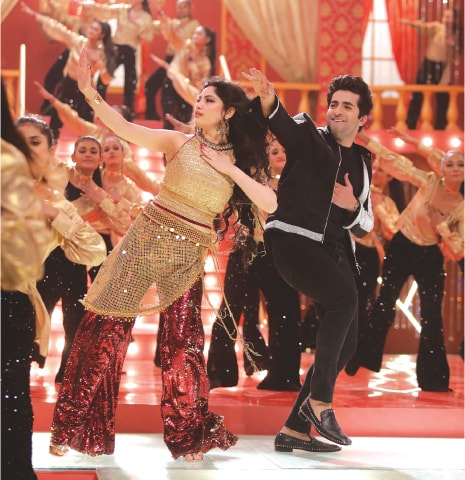

There is a bit where Zuby hoodwinks Bhai Miyaan by taking on a fake persona that gives Saba some room to flex her sensuality. But when you really think about it, other than propelling the plot in a particular direction (and a very interesting direction at that), the character she takes the guise of to fool Bhai Miyaan doesn’t really have cinematic or story worth. She is, at best, a Macguffin — a storytelling tool that instigates a series of events, but remains inconsequential.

These critical revelations, however, come to you in hindsight, because the film — despite being a tad long at two hours and 20 minutes — holds your attention hostage.

Sikandar and Vicky are GNH’s emotional epicentre. Zahid gives a cinema-worthy performance, neither overdoing nor underperforming the typical hero-hero stereotype while making the cop uniform look cool.

One finds small intelligent tidbits to enjoy as the film progresses. For example: note the way Sikandar’s sleeves are tightly rolled up when he plays a badass corrupt cop, and then, when he becomes righteous, the sleeves come down, in respect to his job and uniform. However, unlike typical films, you don’t see Sikandar pulling down his sleeves on screen. Rather, this is but one of the inconspicuously placed blink-and-miss moments that give GNH an intellectual edge when it comes to charting character progression.

Characters, their stories, and their dilemmas are what good films should be about anyways, right? GNH’s makers seem to have an astute understanding of that. By the climax, the characters — especially Jibran — leave a compelling imprint on you, and so, GNH’s parting moments force you to root for a sequel. For once, that might not be such a bad idea.

Parday Mein Rehnay Do: How to Make an Emotional Comedy About Male Infertility

The Lowdown

Wajahat Rauf’s best film till date should be the new template of how Pakistani films should be made: only 90 minutes long and bursting with emotions

Rana (Javed Sheikh) is irked at his neighbour, and he is pissed off at his son. His neighbour (Shafqat Khan) can’t stop breeding children (by the end of the film he has nine kids) while Rana’s son, Kashaan, aka Shaani (Ali Rehman Khan) just won’t look at women.

In any other circumstances, Shaani’s meek, reserved, almost-pious nature might have been applauded by his family, but not here. Rana and his wife arrive at the obvious solution: they think he is into men.

Pressured into marrying Rana’s friend’s daughter Lali (Sadia Faisal) — who harbours a life-long crush on Shaani — the meek young man has no choice but to tell everyone the truth: he has secretly married a girl he loves since college.

Enter Nazo (Hania Aamir), a spitfire with smarts, whose first shot in the film shows her smoking from within the veil on the wedding bed. Nazo and Shaani are your typical non-filmi couple in what is a non-filmi but very cinematically-inclined take on a very serious issue: infertility.

Think Shubh Mangal Savdhaan, but made within acceptable boundaries of Pakistani culture and the censor code. In an era of simplistic political correctness, this is a multifaceted story of a man’s plight when he cannot father children, and how childlessness nearly ruins a family.

Like most of Wajahat’s wares, this is a comedy, and a very smart one at that. Even the title, Parday Mein Rehnay Do, is a testament to the film’s astuteness: with societal stigmas, family bickering and prodding, and condemnation of women (not being able to conceive is never a man’s problem, according to ill-bred norms), just how much should one keep under a veil, the film asks?

PMRD should be the template of how films should be made in Pakistan: a mere 90 minutes long, blazingly paced, expertly cut, and cinematically shot with good music.

The editing by Hasan Ali Khan, reminds one of how Bollywood films are cut: sharp, without lagging head and tails of shots. The cinematography by Asrad Khan is a testament of how you can cinematically shoot a film in what is mostly a one-location film. The soundtrack by Aashir Wajahat and Hassan Ali woos your ears, yet the songs play out in the background. That is a very perceptive and producer-like approach to making a film. Adding song and dance numbers would have broken the film’s tempo. One can see that hard decisions were made for the well-being of PMRD.

Speaking of good decisions, we have Hania Aamir’s cast as Nazo. Hania’s nymph-like physicality hides a very strong, empathetic but resilient young woman who is not beholden to antiquated convictions. Shaani, when he starts out, is much more stubborn, and perhaps somewhat immature. Despite Hania’s well-executed role, this is an Ali Rehman film through and through.

Having witnessed Ali’s career since its inception, this is the actor’s first award-worthy turn. Ali is a natural actor who can’t overact and who, according to my experience of his work, has a limited range. But that’s not a bad thing: Aamir Khan and Edward Norton have limited range; it’s what the actor does within that range that counts.

In PMRD, Ali finally understands and works within the boundary of his acting prowess — and what a performance it is. At one point this writer, and the layman sitting next to him, felt emotional. That is the power of good cinema, and a well-written, expertly directed role: it evokes emotions that reach out to both the common man and the critic.

Pakistani motion pictures have had a strange, female-centric default for quite a few years. With Cake, Punjab Nahin Jaungi, Motorcycle Girl, Load Wedding, Verna, Bin Roye, Parvaaz Hai Junoon, Superstar, even smaller dud films such as Maan Jao Naa, filmmakers, often stemming from television, seem to be stuck on the idea of telling stories that empower women, in films that are primarily designed to attract women audiences. While there is certainly nothing wrong with that line of thought, this mindset stops other genres or gender-unbiased, progressive stories from getting made.

This is where — and why — I feel PMRD is a revelation. Not only is it a story well-told, it is a thoroughly commercial film that doesn’t fall into the gender trap.

Mohsin Ali (Wrong No., GNH) has written an air-tight screenplay that is supplemented by Wajahat Rauf’s pitch-perfect direction. As someone who has reviewed all of Wajahat’s films (all of them lacking in certain regards), I can testify that this is perhaps his most mature project till date…primarily, because he hasn’t written the screenplay himself.

Let me clarify: Wajahat Rauf, along with Yasir Hussain, have been penning their screenplays for a long time now (they co-wrote Karachi Se Lahore, Lahore Se Aagay and Chhalawa — basically, Wajahat’s entire filmography with exception to PMRD). More often than not, a writer is indebted to the words he or she pens in the screenplay. Working on someone else’s screenplay frees Wajahat to concentrate on fresh nuances that might miss his attention otherwise.

With PMRD, Wajahat has become a force to reckon with. He has matured well beyond his preconceived image as a comedy man. He, like PMRD, is much more than what you expect it to be. Engaging, believable, light-hearted yet serious, the film is an intelligent, emotion-stirring film for the masses.

Years ago, I might not have pegged PMRD as an Eid release. Let me admit: I was wrong. If the industry is capable of making films in Wajahat’s template, then a new revival may already be at hand.

Published in Dawn, ICON, May 1st, 2022