In Lyari’s Ali Muhammad Muhalla, stands a nondescript building which speaks volumes of the unrest the area faced in the past when gangs waged war in a struggle for its control. The façade of the building, used now by a local welfare organisation Pakistani Baloch Anjuman, is visibly damaged by gunshots.

The reminders of violence are replaced by a scene of stark contrast, when we climb up the building’s narrow staircase. Upon reaching the rooftop, we find a group of 25 boys is sitting casually on straw mats laid out under the shade of a canopy made of green mesh. They each wield pencils or paintbrushes and sketchbooks, not the choice of weapons the youth of Lyari were generally associated with during the years of gang wars that ravaged this notorious neighbourhood.

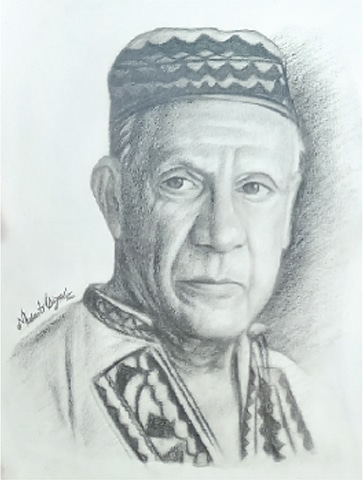

I have come to visit Mehrwan Art institute, run by Lyari’s own artist Raheem Ghulam. Ghulam learnt sketching from local street artists in the 2000s. He later received informal training from Ustad Jan Muhammad Baloch, who also teaches at Mehrwan Art now.

As an art teacher, Ghulam aims to provide youngsters with artistic skills in a safe environment, something he yearned for when he was a teenager. He wants to engage his students in healthy exercise so they do not fall prey to illicit activities.

A local artist in Lyari is empowering young boys and girls to create a brighter future for themselves and the community through art

“Lyari has long been plagued by street crimes, drugs, violence, unemployment and alienation,” Ghulam says, “I don’t want these ills to destroy the young generation. Enough damage has been done.” Art, Ghulam believes, is a powerful tool that can heal people, change attitudes and provide a new perspective on life.

During the years-long unrest in Lyari, Ghulam lost people he knew well, including his neighbours and acquaintances, to drug abuse and crime. Experiencing the loss was a wake-up call for him. “That volatile situation prompted me to be the change I want to see,” he tells Eos. It was in 2015 that Ghulam took the leap to bring a positive change in his community albeit in a grim setting. He began offering art classes in a small room in a slaughterhouse, in a neglected part of Lyari. From the initial group of five students, the class grew quickly in number, so he shifted to a better place to accommodate all the pupils.

Clad in a crisp white shalwar-kameez, 14-year-old Khalfan Baloch draws a portrait in colour pencil of a girl in his sketchbook. His hair falls onto his forehead, but he is too focused to brush it aside. He has been working on this portrait diligently for the past three days. It still needs two more days to complete, he says, while pointing towards the coat which remains to be sketched. The young artist explains that colour pencil sketches are difficult and time-consuming as they require more attention to detail. “You have to master black-and-white medium first in order to start with colour pencils,” he adds.

Khalfan dropped out of school after eighth grade but now looks forward to readmission in the next session. He has big dreams of becoming an animator. Since he does not know of any institute that offers digital arts programmes in his area, he has been taking lessons at Mehrwan Art for the past year. “He is one of my star students,” Ghulam says proudly. “You can see some of his amazing sketches on the wall.” A magnificent sketch of legendary qawwal Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, signed by Khalfan, is astonishing. Other students have also made some beautiful portraits of famous personalities which are displayed in the classroom.

Is Mehrwan an art institute or is it just an art class, I ask Ghulam pointedly. “Mehrwan Art Institute is my vision and a dream that I wish to materialise one day,” Ghulam replies. “It is more of a stepping stone or an elementary art class at the moment where I teach the basics of art to youngsters of Lyari who, otherwise, have no place to learn artistic skills.”

Nayyan is Ghulam’s youngest student at eight years old and interrupted our conversation several times, asking for Ghulam’s help. He joined Mehrwan Art only a few days ago when his summer break began. The young boy hands over the fee to his teacher and takes out his sketchbook and begins to draw a hand clenched in a fist.

There is a nominal fee for these art lessons, and that too is not fixed. Students usually pay 500 rupees to 600 rupees according to their budget. “This little money that I generate helps me sustain this art class and arrange art supplies for those who cannot afford it,” says Ghulam. “With the meagre resources that I have in hand, this is the best I can offer.” Art is for everyone, rich or poor, he says. He feels it is his responsibility to ensure that none of his students are deprived of it because of lack of resources.

The art instructor has designed his own course outline to teach basic sketching to students. He has printed out books of Charles Bargue and Andrew Loomis to guide students through Level 1 and Level 2 respectively. Once the students pass Level 2, they are ready to sketch all by themselves, Ghulam explains.

Art is for everyone, rich or poor, Raheem Ghulam says. The teacher feels it is his responsibility to ensure that none of his students are deprived of it because of lack of resources.

Musaib Sial, 18, is a skilful artist. When asked about how he manages to buy his art supplies amid rising inflation, he retorts, “Do you really think we use original art supplies worth hundreds of rupees?” They cannot be picky, Sial says. They shop at a nearby store or even from a cart vendor. Ghulam makes their sketchbooks himself by cutting large sheets of paper and binding them together.

Twelve-year-old Tayyab was unable to keep up with his school lessons because of his developmental limitations that are still unexplored and unaddressed. “I call him Ishaan Baloch,” Ghulam says with glee, referring to the Bollywood movie Taarey Zameen Per about an eight-year old boy Ishaan Awasthi who suffers from dyslexia.

“Sadly, Tayyab could not find a teacher who would give him individual attention and work on his academic lacking,” Ghulam explains. Tayyab dropped out of school in third grade and found his way to Ghulam’s art class at the age of nine. Luckily, he also found a mentor who saw his creative potential. “I decided to harness his innate creativity and here he is now creating masterpieces,” Ghulam says while flipping through Tayyab’s sketchbook.

True to his principle, Ghulam does his best to maintain an inclusive environment at Mehrwan. The best thing about Mehrwan Art class is that it is flexible and open to everyone, regardless of their social or religious background. It is also open to girls and boys alike. Unlike a conventional art course or a degree, it has no fixed duration. Students learn art at their own pace and can continue their lessons for as long as they want.

Ghulam calls Ali Jan Baloch, 18, his “right-hand man.” Ali Jan wishes to get a professional diploma or a certificate course in fine arts from the Arts Council Institute of Arts and Crafts. Ali Jan’s friend is a former student of Ghulam who has made his way to Arts Council along with three other fellows.

Meer Qais, 20, the eldest student of the class, is a promising artist. Like Khalfan, he wants to build a future in digital arts by joining a professional art school someday. Mehrwan also gets female students who are equally passionate about art.

Ghulam hopes that prestigious art institutes of Pakistan, such as National College of Arts and Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture would pay more attention to aspiring artists like his pupils. He recommends such art schools should fix a quota for Lyari. “There is a dire need to establish an art institute in the area that caters to fine arts and performing arts,” says Ghulam. “Lyari is a hub of artists. It has a number of talented singers, composers, dancers and painters. If I manage to gather the resources, I will set up an institute for my community.”

Ghulam’s mentor, Ustad Jan Muhammad Baloch, teaches painting and water colour techniques free of cost. “The street artists that trained me some 40 years ago did not charge a penny; why would I charge for my services now?” says the humble man, in his sixties. Ustad Jan Muhammad wants to pass on his knowledge to the youngsters and advises them to do the same, so this tradition continues.

Another speciality of this art class is the cardamom tea that is served every day before the end of class. Students and teachers pool in money, while Ali Jan Baloch prepares tea on an LPG gas stove. “The tea refreshes our brains, keeps us charged and we bond over it,” Ghulam says. As an old-school artist who does not understand how online classes work, he can’t imagine virtual classrooms to bring the same joy as sitting together in-person. “The beauty of teaching art lies in face-to-face interaction,” he says. “This online system has taken away the charm of many things.”

This visit to Mehrwan Art class reminded me of Jane Alexander’s quote from Arts Works! Prevention Programmes for Youth and Communities, “Give a child a paintbrush or a pen, and he’s less likely to pick up a needle or a gun. Give a child hope through the arts, and you just may save his life.”

The government needs to give “hope” to people and introduce free training programmes for art mentors like Ghulam and Ustad Jan Muhammad Baloch to equip them with modern skills and educate them on the use of digital technology so they can transfer this knowledge in their communities.

The leading art institutes of the country should organise career counselling sessions, workshops and short courses in such communities with little access to art education. They should also launch programmes to hunt for talent and offer admissions, scholarships and financial assistance to these young artists in order to help them pursue their dreams. Every child is born an artist, Picasso said. The problem is how to let them remain one once they grow up.

The writer is a freelance journalist. She tweets @Tanzeel09

Published in Dawn, EOS, June 26th, 2022