I doubt you will ever meet as naïve a guy as Chaudhry Jameel in Bahawalpur — a city where, in the context of the film London Nahin Jaunga, everyone speaks Urdu in a Central Punjabi accent, rather than in Seraiki.

Jameel fancies himself a poet (to the discomfiture of his townsfolk and family), imports dogs from other countries for dog races (which he routinely loses), and uses puerile excuses to not marry a smart, young woman who anyone — no matter how big of an idiot he is — would deem to be the ideal wife and life-partner.

Jameel can beat up four baddies easily — he is adept at saving damsels in distress in Punjab, as well as clobbering hoodlums in England — but what he can’t do, or rather, what he will deliberately not do, is take a hint.

Jameel has been avoiding marrying Aarzoo, the most gorgeous woman in Bahawalpur. He doesn’t feel the love, nor does he want to marry a desi woman, he says. Aarzoo, head over heels for the oaf, knows this, but what can she do? Love makes you do crazy things.

London Nahin Jaunga is less raucous and is directed with more nuance than Punjab Nahin Jaungi. But if you ignore the basic questions of logic with the story and screenplay, it provides ample bang for the buck for its audiences

In one of his harebrained tomfooleries, Jameel, who has imported a dog from Japan for a dog race, announces that he will postpone the engagement by another year if he wins. He loses, gives the dog — who he quips has a domicile from Tokyo — a stern talking-to because the foreign-born mutt lost to a local bitch, and steels himself for the inevitable engagement.

Approximately 15 minutes into the film, on the night of Jameel’s engagement, where everyone is twirling to the upbeat wedding number Mahiya Vey, enters Londoner Zara with an offer to buy the family mansion.

Zara is mysterious. Her attire of matching black jacket, jeans and boots, befuddles the traditionally dressed locals. She has a spark of innocuous mischief on her face that changes between hurt, resentment and sarcastic bemusement when she is in the proximity of Jameel’s family. One needn’t be Sherlock Holmes to realise that she has a reason to be fuming mad at this family.

To Jameel’s surprise, Zara has an innate, almost insider-like knowledge about the house, its ancestry, ornaments, and even the paintings. You can see where the film is going — even when Jameel can’t — but that doesn’t make the revelations any less effective.

After a series of big-reveals and character introductions (Asif Raza Mir plays the esteemed pir of the town), Jameel is forced to take a pledge that he won’t go to London.

You know, without a doubt, that Jameel and his tag-along sidekick Bhatti, will go to London, and that he will beat hoodlums, crash weddings, deliver applause-inducing ‘awaami’ dialogues, and get the girl (improbable as that may seem).

London Nahin Jaunga (LNJ) is an entertainer of the highest order, in my opinion. Delightfully fresh, quietly funny, and made with exacting attention to production and narrative details, LNJ trounces most narrative problems the films’ producers had in the past, but does fall victim to new ones in the process.

There is an unmistakable flourish of maturity in LNJ’s execution. The tone is less raucous than Punjab Nahin Jaungi (PNJ) — which director Nadeem Baig also directed — and this may catch some viewers expecting similar fireworks off-guard. One feels that Baig (who also directed Jawani Phir Nahin Aani and its sequel), is making deliberate creative choices with tone and pacing, while trying to remedy his own shortcomings of the past (he still needs to work on his leading pairs’ chemistry, by the way).

Baig’s easy-going style masks an impressive improvement of his command over filmmaking techniques and aesthetics (notice the choreography of the camera in the context of the scenes). As expected, his pairing with Khalil-ur-Rehman Qamar’s screenplay and dialogues, brings a fresh perspective to a familiar story.

In lesser hands, the film could have turned overly melodramatic. The scenes blend laugh-out-loud one-liners in midst of serious conversations; this creative decision gives the film a unique mood that masks some fundamental problems with the plot.

The screenplay barely wastes minutes defining the characters. Jameel is staunch in his belief that he will get the girl. Zara doesn’t care about Jameel’s existence. Aarzoo knows where she stands. LNJ is not a love-triangle, per se.

One feels that the characters hardly walk the path of personal maturity when it comes to individual growth, as the film unravels its core plot. They remain steadfast to the type of people they started out as. Jameel, in particular, doesn’t change a bit.

The main story, about marrying for love, revenge, retribution, accepting and atoning for transgressions of the past, and rectifying self-imposed rural customs, is set-up throughout the pre-intermission section. The second-half, made up entirely of Jameel’s trip to London and his unwavering pursuit of Zara, adds little in the story department. One’s interest takes a serious ten-minute dip here, where the film drags before the ramping-up to the climax.

Speaking of the finale: it just happens out of thin air in a rushed bid to wrap up the story. A few sequences leading up to the culmination would have helped the story (the film only has one scene in this regard; it is an angry confrontation between Aarzoo and the pir played by Asif Raza Mir).

LNJ, at this point, needed a deft touch, rather than a straight finish, since it links directly to the fundamental reason for Zara’s angry visit to Pakistan at the beginning of the film.

There are questions of basic logic that shake the foundations of the film. For example: What did Zara accomplish by coming to Bahawalpur? Was she here just to trigger events and memories of a long-dead past, and then just walk away after confrontations? Does she come to Bahawalpur simply to inflame passions and exasperate people by declaring a fact, and nothing else? Was it just as easy for her to nearly abandon the pursuit of the agenda that brought her to Pakistan in the first place?

When we learn Zara’s side of the story, we realise that she is not after worldly riches, recognition or revenge. The only action her visit actually accomplishes is triggering our simple-minded hero into Romeo-mode.

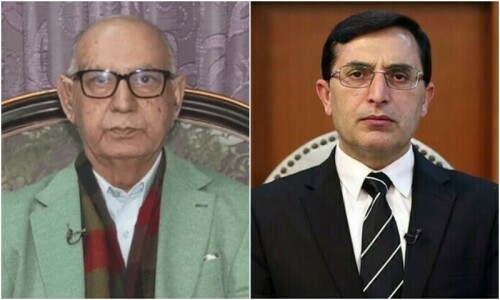

Humayun Saeed is brilliant as Jameel, the forlorn hero with a good heart, very little common sense and a natural predilection for dogged pursuits of things that catch his fancy. The role cements Humayun’s status as the current generation’s best leading man, while giving him a different, albeit simple and flawed hero to play.

Mehwish Hayat, who plays Zara, has a much more layered character — but, like her character in PNJ, she inexplicably falls for the brute who doesn’t take no for an answer.

The actress glows in the role both performance-wise and literally (the radiance on her face is partially the allure of the actress’s charm, the filters on the camera and post-production gimmickry).

Despite the aforementioned flaws with the character, Mehwish carries the weight of the narrative with flawless posture, rousing emotions without ersatz monologues or preachy declarations. In fact, one of the most effective scenes of the film — where a major revelation happens — takes only minutes to make its point, without any sermonising.

Notice, at this moment, the fitting use of the background score by Shani Arshad, and then listen to how and when that background score pops up during the entire film. The masterful restraint (especially the use of the score) is one of Nadeem Baig’s new fortes, I believe. The other would be the effective use of his actors.

Actually, make that some of them.

Sohail Ahmed, a permanent fixture of Humayun’s films of late, is a hoot…but then you knew that already. Saba Faisal and Saba Hameed carry their characters with relative ease. Iffat Omer, Salman Shahid, Asif Raza Mir, despite one or two excellent scenes, contend with bare-minimum screen time.

Vasay Chaudhry, whose comedic yet somewhat serious performance as Zara’s bestie Harry, could have had more scenes that gave weight to his character. He does, however, get a closure, albeit cheesy, by the very end of the film.

Mirza Gohar Rasheed’s character Bhatti could have also benefited with the love Harry gets in the screenplay. Despite being headlined in the promotions, Bhatti functions little more than a bounce-board for Jameel’s dialogues. Irrespective of being in almost every scene, you hardly get to know Bhatti. One feels that the screenplay doesn’t care to make him stand out. For an actor of Gohar’s ability, this is a missed opportunity.

Worse off than Gohar is Mehr Bano, who plays one of the girls who is close to Aarzoo; utterly wasted, her character has nary a dialogue.

Kubra Khan is gorgeous and phenomenal. Her scenes — especially in the first-half — add emotional value to the story. The astute call to not shoe-horn Aarzoo when she is not needed maintains the fluidity of the pace.

Ultimately, pace and giving the audience bang-for-the-buck, play a more vital role than any actor in LNJ — and a bang-for-the-buck the film definitely is.

Released by ARY Films, ‘London Nahin Jaunga’ is playing in cinemas and is rated ‘U’.

Published in Dawn, ICON, July 17th, 2022

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.