AT the time of independence, Pakistan had no industry worth its name and therefore the corporate sector, even in its rudimentary form, was non-existent. The government, therefore, had to play a catalytic role in nurturing the development of the private sector by pursuing policies that protected the newcomers from international competition.

This led to the emergence of a dynamic and vibrant private sector which became the engine of growth. Very few people realise that from almost scratch, Pakistan’s manufactured exports, according to the World Bank, were by 1969 higher than those of Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines. This was by no means a mean feat and the country should have taken pride in this exceptional performance that was registered within two decades. But the process was disrupted because of some unintended consequences that had adverse political implications.

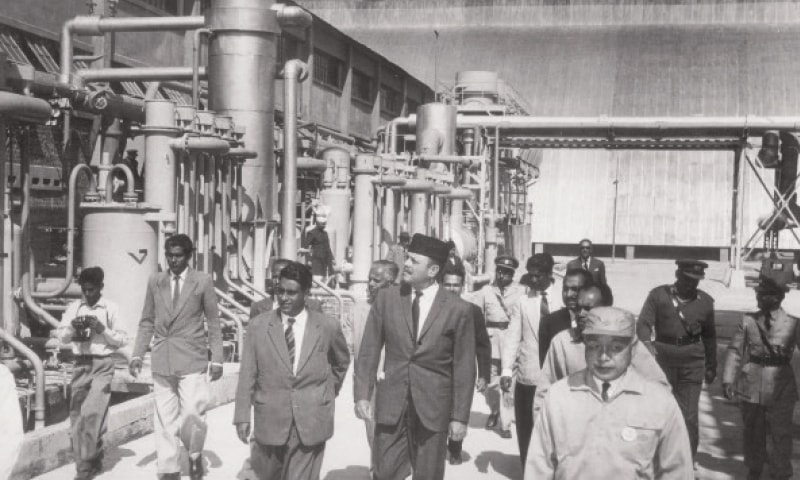

The slogan of ‘22 families’ owning the majority of industrial assets and the location of most industrial units in West Pakistan gave rise to a tumultuous reaction in the country. The socialist paradigm that was very much a critical factor in Cold War days comingled with the political movement against military dictator Ayub Khan. After the separation of East Pakistan and the election of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, charismatic leader who came to office on the promise of breaking up the concentration of economic power, the country suffered a severe setback.

Large-scale industries, banks, insurance companies, educational institutions were all nationalised. They were run by bureaucrats who had no experience of running a business enterprise. The decision-making that has to be swift in case of business was too concentrated in the ministry of production and the boards of management. The country detracted from its trajectory of rapid economic growth.

A once thriving industrial sector was thrown off track by Bhutto’s nationalisation policies. Dr Ishrat Hussain asserts that only a higher productivity, investment in ‘sunrise’ and high-tech ventures, and a better-trained labour force can fuel economic growth in Pakistan.

Damage control

The damage was not controlled until Nawaz Sharif came to power and introduced privatisation, liberalisation and deregulation as the pillars of an extensive economic reform agenda. Although subsequent governments did not reverse the agenda, due to the dictates of political survival, they did not implement it as vigorously and diligently as it ought to have been done. The country muddled through and from being one of the fastest growing developing countries in the first 40 years of its existence, it has become a laggard in the region, and India and Bangladesh, who were way behind in all indicators, have surpassed us.

It is no use lamenting the past, but the need is to design and deliver policies that would lead to the revival of our economy as quickly as possible. Let us begin by asserting that there is plenty of empirical evidence over the last seven decades from development literature that the binary — markets vs government — is no longer valid and has become outdated. We need both a strong and effective government and well-functioning competitive markets regulated by the government. The public and private sectors should work in partnership for common agreed goals, each where they have comparative advantage.

There are both market failures and government failures and as long as these failures get redressed, the country would be moving on the right track. Global financial crises, pandemics, inequality, technological advances and the climate change agenda have convinced us that timely and appropriate government interventions are required to address these issues. On the other hand, the government should keep its hands off when it comes running businesses as experience with the public sector running business enterprises has not been very successful in many countries.

Higher demand, higher imports

It has become quite clear that the domestic productive capacity to meet the aggregate demand when the country is growing fast is inadequate and creates balance of payments problem as the demand spills over into higher imports. In turn, we have to borrow in order to finance these imports as our foreign exchange earnings from exports, remittances and foreign direct investments (FDIs) are not sufficient to meet the rising import bill. The consequences of this boom-and-bust economy is that we have to meet periodic crises, approach the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other donors to meet our external financing requirements.

To avoid depletion of our foreign exchange reserves, we have to allow the exchange rate to depreciate, interest rate to rise to contain inflationary pressures, and allocate a higher amount of our budgetary revenues to meet debt-servicing costs. The rising fiscal deficits continue to reduce the space for public-sector investment.

Under this scenario, the private sector has the obligation to raise investment rates by expanding production for domestic and international markets. Agriculture input supply, marketing and processing have remained stuck in medieval modes and the private sector has not established warehouses, cold chains, agro-processing units, certified quality seed companies, advisory services, veterinary services, artificial dissemination units, equipment and implements rental shops to increase domestic production of cotton, wheat, sugarcane, powdered milk, pulses, vegetables and fruit, oilseeds, fodder, etc. that can save at least $10 billion of imports every year.

Similarly, in industrial and services sectors the realistic exchange rate and concessional financing under temporary economic refinance facility (TERF) has o`pened opportunities for efficient import substitution and backward linkages in automobile, mobile manufacturing, pharmaceuticals, electronics etc. Information Technology (IT) and IT-enabled services have emerged in recent years as a promising avenue for both domestic digitalisation agenda as well as for exports. Investment in innovation and technology should be undertaken by our well-established businesses rather than following the herd instinct. Petrochemicals, oil refineries and steel are the most critical industries for investment which we have neglected for decades.

Share in exports

Most successful countries have benefitted from active participation in international trade as world exports have been growing twice as fast as the global output. Our share in global export markets has declined form 0.2pc to 0.15pc in the last 30 years, and export-GDP ratio plummeted to 10pc from over 17pc in 1992. India was able to jump from 7pc to 23pc by 2013, and Bangladesh from 6pc to 19pc. Both these countries were able to significantly surpass Pakistan in capturing the share in global exports (India 1.71pc and Bangladesh 0.24pc).

Global economic conditions in this period, except for the crisis of 2008, were buoyant and highly favourable to developing countries, and their share had risen faster at the expense of the developed countries. At the turn of the millennium, 90-97pc of merchandise exports used to finance Pakistan’s imports, but this capacity has dwindled to only 47pc. Not only has export growth levelled off, the composition of our exports has also remained unchanged for the last three decades.

Two-thirds of our exports are concentrated in a few agricultural raw materials-based and unskilled and semi-skilled labour-intensive products, such as textiles, rice, leather, etc. We remain focussed on traditional, stagnant, slow-moving sunset exports rather than dynamic, fast-growing strategic products in the medium-tech and hi-tech sectors. The share in hi-tech exports has remained static at less than 2pc while low-tech exports account for two-thirds of the total, down from one-half in the 1980s.

The public discourse so far has been mainly and disproportionately centred around the government’s role in export promotion and very little attention has been paid to those ‘who produce, distribute and sell these products’ — the main private-sector actors in the scene for making our exports competitive. The captains of industry in the export sector should no longer devote their attention towards Islamabad for extracting concessions, tax breaks, subsidies and low interest rates, as this would keep them dependent on the crutches provided by the government of the day and keep them entrapped in the present low-productivity equilibrium.

They should tap the hidden wealth in industry through labour productivity gains by hiring professionals, restructuring internal organisation, revamping logistics, acquisition methods, entering into joint ventures and bringing in FDI, and mobilising capital for expansion and investment in sunrise industries through initial public offerings (IPOs).

The most persistent and lingering phenomenon that needs to be tackled is low productivity in our export industries, which is amongst the lowest in the region. We may be a low-wage country, but, adjusted for productivity, efficiency, quality (rejection rate), reliability and innovation (design), we are an expensive country. A labour force with average schooling of five years and 40pc of the population being illiterate place Pakistan at a disadvantage compared to its competitors. It therefore becomes imperative for the exporting firms and the government together to turn this around and not accept the situation as a given.

The present practice of considering wages paid to labour as a financial burden, hiring transient, temporary and contractual workers, non-allocation of resources for training and skill-formation and upgradation only aggravates the problems. Many firms have done remarkably well in treating their workers fairly, training and upskilling them and taking care of their welfare. The attrition rates in these firms are low, morale is high and loyalty to the employer unshakable. The owners of these firms have reaped the dividends and are continuing to do so at a heightened level.

Finally, there is tremendous political and business lobbyist pressure to protect domestic final goods industries by imposing high tariffs. Very few economists would disagree that the ‘infant industry’ argument and ‘learning-by-doing’ justify time-bound performance-related protection. However, in Pakistan we have become used to open-ended and continuous extension of concessions, exemptions and high tariff rates. Entry and exit rates of firms exporting their goods and services are therefore low, product diversification has actually shrunk, sectoral composition remains unchanged from the 1990s, and geographical concentration is elevated.

The latest estimates of effective rates of protection (ERP) are not available, but an earlier study by the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE) had concluded that these rates had declined in the early 2000s. But the introduction of additional custom duty and regulatory duty in the last five years has increased the ERPs. Average tariff rates and the number of tariff lines were also rationalised, except for a few items, but these have also been tampered with in the last decade with the average rate rising from 12pc in FY15 to almost 20pc in FY20, which is almost twice as much as is the case with our competitors, and in China it is 5pc.

It is not realised that in a world dominated by global value chains, tariffs on imports of components, ancillary supplies and intermediate inputs act as tax on exports. Studies have found that reduction in import duties help minimise input costs in downstream industries, some of whom then become competitive in third-country markets. Let’s start living in the 21st century.

The writer carried out extensive institutional reforms as SBP Governor and IBA Director. He chaired the National Commission for Government Reforms (NCGR) in 2006-08 that produced a comprehensive plan for civil service reform and restructuring of the federal, provincial and local governments. In 2009-10 he was head of the Pay and Pension Commission, and from 2018 to 2021 adviser to the prime minister on institutional reforms and austerity.

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.