The day the war broke out in Ukraine, I woke up bleary-eyed, thinking only of my son who was there for his medical studies. In a state of feverish restlessness, I was shuffling in and out of my study room and wondering when and if my wife would hear from my son. She was crying bitterly. I tried to console her by saying that there were many other students out there along with our son, but it was all in vain.

I retired to my study when a million thoughts came crowding into my mind about our family and how it branched across three different continents. I thought back to the one night in the pre-Partition era, where my grandfather, who stood on a ship anchored in Calcutta ready to set sail for Canada the coming day, returned.

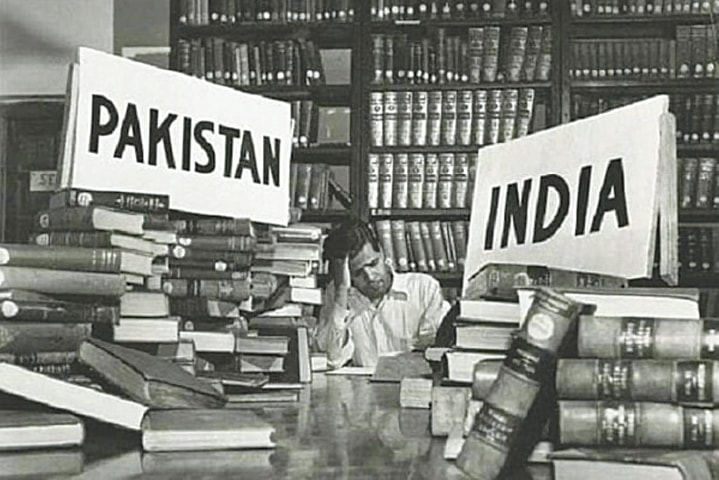

Before Partition, my grandfather moved from a village in north Punjab to Mandi Chishtian in Bahawalpur district, where he started a prosperous business and made a decent life for himself.

However, after Partition, he returned to his native village penniless and hopeless, and thought of resettling there. He was, of course, starting from scratch. He decided to set up a garments’ kiosk in the sleepy village, shorn of any hustle and bustle. His business did not flourish as much as he had hoped, making it difficult for him to attend to the needs of his two children.

The harrowing realities of a son held up by war on an alien land today brings back narrated pre-Partition memories

It was then that he hatched a plan to go to Canada by ship. All he could lay his hands on were a few items of gold jewellery, which he had accumulated for my grandmother in his halcyon days in what was now Pakistan. He pawned all her jewellery and raised some money to seek new pastures in an alien land, far from the comfort of his milieu.

On an impulse, he decided to accompany his friend to board the ship from Calcutta. They spent one night in the city and, the next morning, they were to board the ship slated to sail to Canada. As the coach of the ship walked them through the itinerary of the long voyage in a rushed late-night session, my grandfather got scared and, in trepidation, took another rash decision. He ditched his plan and went back to his village.

My grandmother often teased him later that he got scared by the deafening sound of the ships veering around the shores of Calcutta.

But it was in fact a premonition that made him turn his back on his plans to seek a life in a faraway land. While waiting on the dock, he imagined what it would be like — his job in the new land, provision of necessities for his wife and kids and, of course, their unpredictable careers with inadequate resources. Unlike Buddha’s journey, his was a materialistic expedition and not a spiritual one; he did not feel like leaving his family in the lurch. How could he take his family along with him at that juncture?

I realised my ancestor’s anguish fully well when I felt the stab of separation from my only son as he left to pursue his studies in Ukraine. I had also spent all my earnings on his trip and tuition. Having learnt from my earlier hardships, I habitually began putting aside some percentage of my earnings to prepare for a rainy day and that habit helped me realise my son’s academic aspirations.

Unlike Buddha’s journey, his was a materialistic expedition and not a spiritual one; he did not feel like leaving his family in the lurch. How could he take his family along with him at that juncture?

I taught as a Professor of English in a university in north India and eventually, was invited to the University of Toronto, Canada, as a post-doctoral research fellow, for pursuing research on “The Search for Roots in Canadian and Indian Fiction in English”. The research topic selected so randomly turned out to be totally relevant to my exile, as my venture proved to be akin to the adventures of my family members.

My son’s odyssey is perhaps tinctured with the achievements of other family members, but he took the road less travelled. That was one of the reasons that I kept the preparations for his departure to Ukraine a hush-hush affair.

That morning when Russia invaded Ukraine, while sitting on a couch in my study, I was afflicted with multiple racing thoughts about the safety of my son. I turned to the Urdu poets whose books were neatly shelved in my study to seek solace.

I was murmuring the powerful couplets of Allama Iqbal, Mirza Ghalib and Faiz Ahmed Faiz to soothe my tortured self, when my wife announced that she was receiving a WhatsApp video call from my son. It broke my heart to see my son’s morose face as he was narrating the gory incidents of murder and mayhem happening in the city he was in. He was holed up in an underground metro station turned into a bunker.

For sure, the frustration he felt was for the suffering students who had been rendered homeless and penniless by the volley of bombardments and missile attacks. But the realities of ground zero as described by my son were nightmarish. A maternity ward of a hospital was razed to a rubble; a child got stranded and crossed the border searching for his parents who were victims of a missile attack; a man was huddled into a military truck and, later, released on humanitarian grounds.

As I listened to the surreal scenes of destitution and hunger he witnessed, I was struck by the magnanimity of Ashoka the Great, who suffered the pangs of regret and remorse and underwent a cathartic experience after the war of Kalinga. However, I am unable to visualise any such cathartic experience on the part of the perpetrators of war in Ukraine!

Quite manifestly, the exiles of the protagonists of epics severed from the bosom of their beloved lands is still palpable in the day-to-day exiles of men and women shuttling from one country to another, one continent to the other, in a struggle for bread in alien spaces. In the process, all of us suffer from financial toothaches and mental agony.

But much to our relief, a new lease of life was unleashed in us when my son called us in the wee hours of a fine morning, informing us about the details of his return flight. When my wife and I went to receive him at the Calcutta airport, my wife was sobbing and hugged him for so long that I could easily conjure up similar images of helplessness and hopelessness that my grandfather had described so vividly when my grandfather decided to return home decades ago — the return of the native!

The writer is a freelance journalist and a writer of fiction based in Toronto

Published in Dawn, EOS, September 18th, 2022