From Cambridge to Helario Pir: Exploring the gender-water-energy nexus in Thar

As a social science researcher focusing on energy, the best part about my work is getting to know people, their everyday lives and interactions with energy, and every so often, the opportunity to observe and experience this on the ground through fieldwork.

Earlier this year, I visited Helario Pir, a village located in Sindh’s Tharparkar district, at the foot of Pakistan. My visit there was linked to a research project investigating the socio-technical feasibility of renewable energy provision in Thar to help improve people’s lives.

Helario is one of hundreds of villages scattered across the Thar desert that still lack grid access to electricity or water. For context, the Thar desert is regarded as the only fertile desert in the world, with rain-fed agriculture as the primary source of sustenance.

With a tropical desert climate, Thar experiences extreme heat during summer days — reaching temperatures of 45°C-48°C — while the nights are cooler, and an average temperature of 20°C in winters. Increasing frequency and severity of droughts in recent decades has resulted in reduced agricultural yield, leading to increased poverty, food insecurity and water scarcity.

Before this trip, I had never visited Karachi, let alone Tharparkar in Sindh, and so very much looked forward to experiencing a different side of Pakistan. With the help of my research colleague and acting tour guide, Associate Prof Gordhan Das Valasai, we set off on a nearly five-hour journey to Helario Pir, located about 300kms to the east of Karachi.

The journey took us across the 200km belt of the Indus River Delta. Due to the seasonal monsoon and prevailing rainfall this year, the area was lush green with rice paddy fields abound. Every scene felt like an Instagram moment — small mud and wood thatch huts lined with mangrove trees, with livestock lazily grazing alongside the paddy fields that stretched as far as the eye could see.

Eventually, we entered Tharparkar district, marked by a visible change in the terrain. The undulating sand dunes of the Thar desert now replaced the delta plains. These rolling dunes are generally of various heights and in a state of continual motion, separated by sandy plains and low barren hills, or bhakars, which rise abruptly from the surrounding plains.

There was a serene and gentle beauty to Thar that was almost mesmerising. In August, the fertile desert it is rich with greenery and shrubs of various shapes and sizes — a landscape of weathered Khabbarr, Kandi and Kumbhat trees, prickly scrubs of Ak and the many varieties of cacti.

Unperturbed in its timelessness, its stillness is unmoved by the rustling leaves or the leisurely gait of grazing camels; untouched and far-removed from the chaos of modernity, yet resilient and unwavering with a quiet dignity.

After travelling for about 30kms into the desert, we reached the village of Helario just off the Mithi-Badin highway.

To my delight, we were welcomed into the village by none other than a peacock, its iridescent tail feathers fanning out in a beautiful display of colour. Peacocks roam freely here in the desert. In the settled silence of the village, the tranquil atmosphere was only broken by the occasional cry of a peacock.

On meeting the villagers, I realised that it wasn’t just peacocks that displayed such luminous colours. My first impression of the village women was how beautifully and vibrantly dressed they were, in their traditional Thari attire adorned with bangles and jewellery.

Some have described this buoyancy as representing ‘colours of hope’ against the lacklustre background of their reality. I sat down with a gathering of married women — unmarried women are generally not allowed beyond the bounds of their house — in one of the mud thatch huts to talk about their daily routines and access to water and energy.

Without doubt, the women of Tharparkar face extreme challenges of hardship and poverty, compounded by a lack of education opportunities, availability of proper health services and inadequate infrastructure and facilities.

As a drought-affected area, the human development index rating is lowest for the district and according to the UNDP, 87 per cent of Tharparkar’s population lives under the poverty line.

In Helario Pir, while there is a secondary school for boys, there is no high school for girls. And while the boys go to neighbouring cities for higher education, it is unconventional for girls to get an education beyond the village.

Added to this are the responsibilities of household chores and taking care of the livestock. Since many men leave the village in pursuit of education or income, it falls upon the women left behind to take care of the household.

As previous studies have shown, women often work long hours, participating in crop cultivation, livestock management, dairy production, forestry, in addition to completing household chores such as food preparation, fetching water, supervising and raising children, and care for the elderly.

In our conversations, women talked about the substantial time and effort spent on collecting water and preparing food for their families.

Water collection and the precarious access to water is by far the most challenging issue faced by the villagers.

Climate change has impacted the frequency and intensity of rainfalls in the region, giving rise to increasing uncertainty and unpredictability of weather patterns. Studies show that underground water levels have also decreased over time, a fact acknowledged by the villagers.

Here again, the gendered impacts of water scarcity are evident, as women are traditionally responsible for water collection for their households and livestock and have had to spend more time and energy into drawing water from the nearby wells over recent years.

Although this ground water is suitable for use in washing and for livestock, its brackishness makes it not suitable for drinking. Over time, underground water tanks have been installed in the village with the help of donations from non-profit organisations. Water tankers are purchased to fill these tanks every few months for about Rs8,000 — a cost that is high but necessary for the community’s basic survival.

This isn’t to say that other better technological solutions haven’t been considered.

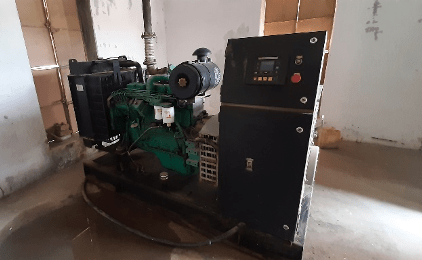

In fact, a Reverse Osmosis (RO) plant of 75,000 GPD (gallons per day) capacity was installed in the village more than 10 years ago by the local government with the help of millions of dollars of international funding.

The size of the plant was sufficient to provide water for the entire 400 household village. However, in 2020, its operation came to a standstill.

This was partly due to the government seizure of payments for fuel for running the plant’s diesel generator, and partly from the lack of technical expertise and local equipment for its operation and maintenance.

Another important factor here was the water quality obtained — since the treated water was still not considered suitable for drinking, the village women found no reason to travel and carry water over longer distances when they could obtain the same from the nearby wells.

Unfortunately, this outcome is not unique to the Helario RO plant. According to reports, of the more than 600 RO plants installed throughout Tharparkar, around 400 have malfunctioned, while numerous others have had parts gone missing, with countless cases of corruption.

The availability of clean and potable water hinges on the availability of clean energy. After water, access to electricity becomes a major concern.

Here too, the village has not remained untouched by technology, although interventions remain small-scale.

In the absence of a grid connection, the use of solar-panels, solar-powered plates, devices and rechargeable batteries have become common in recent years. In this case, affordability of batteries and solar panels, as well as their local availability become key issues. While those better-off are able to install solar panels to power lights, ceiling fans and other small electrical equipment, the poor barely make do with small solar-powered torches.

Here again, gender differences become apparent, since the most significant need for evening lighting is for cooking done by women. What’s more, cooking is still majorly done using mud stoves and firewood, which pose severe health risks for women. Alternative clean cooking energy sources are yet to be seen in the village.

Water and energy are deeply intertwined and have gendered impacts on everyday practices. Despite their limited access to both, the village women remain optimistic and hopeful for a better future.

Perhaps life in the desert comes with resilience and learning how to persevere. I found these women to be extremely resourceful and hardworking, diligently managing their households, and making the most of every opportunity.

Any spare time left is spent in sewing and embroidery work, a skill that can be significantly harnessed and refined with better provision of electricity.

While the women are keen to get better access to electricity and water, their sense of identity and belonging remains bound to the desert, the love for their land apparent in every conversation.

In light of the techno-economic constraints that challenge grid expansion to the remote rural areas of Pakistan, decentralised and distributed renewable energy solutions can provide a viable and much needed alternative, provided they are designed to address people’s needs — access to clean, safe and easily accessible water, electricity for household chores such as cooking, and power for productive uses — opening doors for women to become economically empowered.

Moreover, provisions should also be made for electricity services that address women’s need for education and information as a basic right, ultimately leading to resource efficiency and sustainability.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned as a social science researcher, it’s the degree of entanglement that exists between social and technical systems.

Many scientific studies emphasise and go on to quantify the untapped renewable energy potential in Pakistan. And while they provide useful techno-economic statistics for energy production and distribution, the picture remains incomplete without considering the socio-cultural factors that determine, for example, the gendered access and needs for energy.

Unless these are considered alongside the more technical and financial decision-making, there cannot be sustainable and equitable energy for all. Until then, the true untapped resource in the country remain its people, particularly the Pakistani women.

This research was made possible due to the generous funding provided by the British Council Researcher Links Climate Challenge Workshops Grant: Delivering a Sustainable Energy Transition for Pakistan. I would also like to thank Prof Gordhan Das Valasai of QUEST, Nawabshah, for some of the amazing photographs of the village.