PARIS: Five months after the United States announced the killing of Al Qaeda’s leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in Afghanistan, the global jihadist group has still not confirmed his death or announced a new boss.

In early August, US President Joe Biden said US armed forces fired two missiles from a drone flying above the Afghan capital, striking al-Zawahiri’s safe house and killing him.

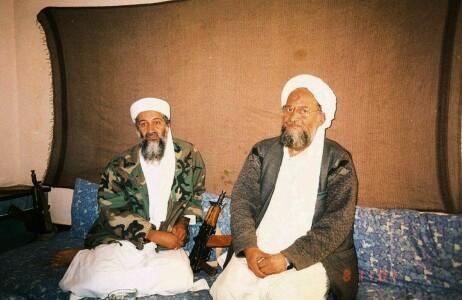

But the group’s propaganda arms have continued to broadcast undated audio or video messages of the bearded Egyptian ideologue who led the group after US special forces in 2011 killed its charismatic founder Osama bin Laden in Pakistan.

“This is really bizarre,” said Hans-Jakob Schindler, director of the Counter-Extremism Project think tank.

“A network only works with a leader. You need a person around which everything coalesces.” Almost all options remain open.

“It could of course be the case that the United States is wrong about his death,” researchers Raffaello Pantucci and Kabir Taneja wrote in early December on the Lawfare website.

But “this would seem unlikely given the confidence with which President Biden publicly spoke about the strike”.

Successor in hiding?

Another possibility is that the group has so far failed to make contact with Zawahiri’s most likely successor, his former number two, who goes by the nom de guerre Saif al-Adl or “sword of justice”.

A former Egyptian special forces lieutenant-colonel who turned to jihadism in the 1980s, he is believed by observers to be in Iran.

The Islamic republic’s Shia rulers officially oppose Sunni Al Qaeda, but opponents have repeatedly accused Iran of cooperating with the network and giving sanctuary to its leaders.

For Schindler, Saif al-Adl “is a liability but also an asset for the Iranian regime”.

According to its interests, Tehran could decide to hand him over to the United States, or allow him to attack the West.

Al-Qaeda may also be keeping quiet about Zawahiri’s demise under pressure from the Taliban, Pantucci and Taneja suggested.

The group issued a carefully worded statement in August, neither confirming Zawahiri’s presence in Afghanistan nor acknowledging his death.

“Their decision not to comment could be part of their efforts to manage their fragile but deep relationship with Al Qaeda, while also avoiding drawing attention to the foreign terror group presence in direct contravention of their agreement with the United States,” they said.

Saif al-Adl could also be dead or in hiding to avoid the fate of his predecessor or the two last leaders of the network’s main rival, the militant Islamic State group, who were also killed last year.

Zawahiri did not try to emulate bin Laden’s charisma and influence after he took over the network but played a key role in decentralising the group.

Al Qaeda is today a far cry from the group that carried out the September 11, 2001 attacks against the United States.

It now has autonomous franchises scattered across the Middle East, Africa and Southeast Asia that are far less dependent on central command than previously in terms of operations, funding and strategy.

‘Limited importance’

Barak Mendelsohn, a US-based Al Qaeda expert, said it was hard to tell why the group was taking time to announce a new leader, adding that the delay was not “very consequential”.

“Ultimately the wait reflects Al-Qaeda central’s limited importance,” he said.

“It’s a symbol unifying groups across borders, but its operational relevance is low.” Al Qaeda’s arch-enemy Islamic State has faced similar difficulties in filling its leadership since its “caliph” Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi killed himself during a US raid in Syria in 2019.

After his two successors were killed last year, IS this autumn chose a relative unknown as its new chief, who claims heritage from the prophet’s Quraysh tribe to boost his legitimacy.

Tore Hamming, a fellow at the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation, said it was not essential for Al Qaeda to have a symbolic leader to speak in its name.

“We have seen with the Islamic State (group) since 2019, it does not necessarily matter,” he said.

IS elected new caliphs, but “no one knew who they were and never heard from them. Yet still affiliates remained loyal,” he explained.

“For Al Qaeda it could be the same, just with a council of senior figures playing the role of an emir,” or leader.

Published in Dawn, January 4th, 2023