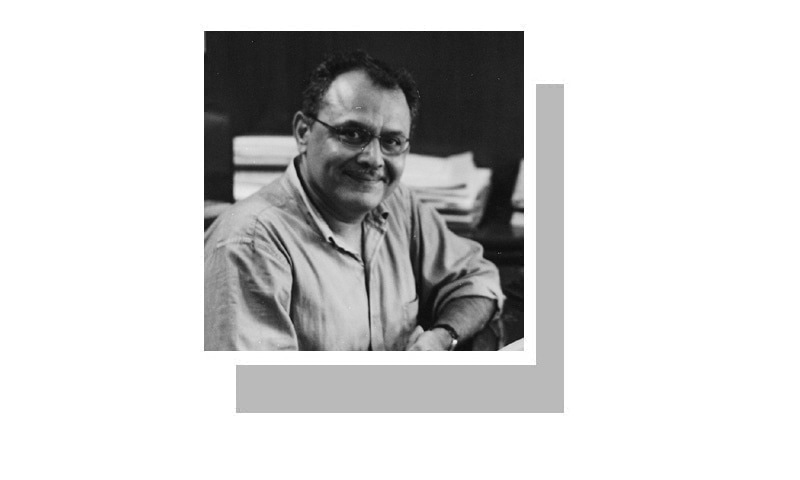

“When I was brought into prison, a jail official told me not to worry because I’d get bailed out in 15 days. I shuddered at the prospect of having to spend two weeks behind bars and wondered how I’d survive,” Junaid Hafeez told someone who visited him in prison soon after his arrest. That was 10 years ago.

He is a prisoner nobody is interested in. He was charged under blasphemy laws in 2013 in the most unfortunate circumstances, because he brought a fresh perspective to teaching his students in Multan’s Bahauddin Zakariya University and earned the wrath of a coterie of teachers — adherents of right-wing ideology.

His legal defence team maintains to this day that the so-called evidence against him was fabricated and patently flimsy, but in the environment we have in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, at least lower court judges are known to err on the side of caution — ie, decide less on the merit of the case and more on the grounds of self-preservation.

You’d ask why do they not walk away from a job as demanding as deciding about someone’s liberty, life and death as a matter of routine if they don’t have what it takes to be able to face up to any consequences of upholding the truth? But let’s not kid ourselves.

How bleak life must be for a brilliant young man, who returned to the country to bring light to university students.

We aren’t made of the stuff where principles such as transparent dispensation of justice is the most overriding concern of our robed interpreters of the law, no more than it is of the parliamentarians or defence personnel, or anyone else in society for that matter. Perks, privileges and position in society is what matters, and the fastest route to riches or at least financial stability.

Such cases are seen as dynamite. At least privately, some such officers of the law cite examples such as what happened to Junaid Hafeez’s lawyer. Rashid Rehman, the Multan-based human rights lawyer who took up the case, was warned in open court not to take up the brief. He expressed the fear he may not be able to make the next hearing.

However, the brave man did not relent and continued to represent Mr Hafeez. He was shot dead in his office in 2014. Nobody has been arrested or faced justice for that murder. The trial saw some half a dozen presiding judges come and go. Finally, six years later, in 2019, he was sentenced to death by a trial court inside Multan jail.

A member of the defence team, who described the verdict as utterly flawed, was optimistic that even in the present environment it would be vacated on appeal. All that needs to happen is for a date to be set for it to be heard on merit.

Using my very humble, and in the event useless, contacts, I tried to have a message conveyed to the senior most judicial figure of the country, pleading that something could be done so the appeal is heard but strictly on merit.

Rather foolishly, I hoped that someone who was instrumental in sending two sitting prime ministers packing and had acquired a reputation for trying to clear the long backlog of pending cases before the highest court, would see to it that justice was not denied by virtue of being delayed for a young man; an educated young man, whose liberty was taken from him, and whose life now hangs in the balance on pretty dodgy grounds. But pity me, even the nation possibly; nothing happened. Junaid Hafeez remains a prisoner. The appeal has not gone very far.

It breaks my heart to imagine how bleak life must be for a brilliant young man who returned to the country to bring light to university students. He elicited so much fear and hate among his obscurantist and, as my own experience with such a lot tells me, utterly incompetent peers that they not only got him kicked out of a job, but also of any semblance of a normal life.

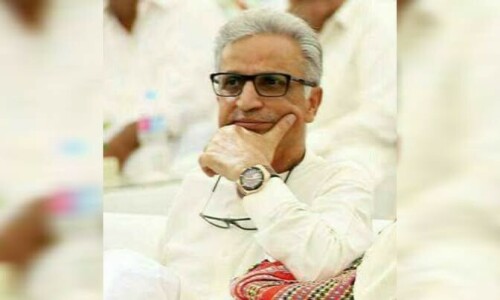

There are endless travesties. Naqeebullah Mehsud, the unarmed young Waziristan man, picked up and killed by the Karachi police in cold blood. His killers have just been given a free pass by the trial court. Lawyers representing his family say they’ll appeal the acquittal as it flies in the face of a mountain of evidence.

Naqeebullah’s outrageous and evil murder led to the creation of the Pakhtun Tahaffuz Movement, one of whose leaders, an elected MNA from a Waziristan constituency, Ali Wazir, remains in prison. He lost 17 close family members to the TTP’s murderous violence. His crime? Calling out the follies of the security set-up in formulating policies based on the now absolutely discredited good, bad Taliban argument.

No superior court has stepped in to stop the nonsense and said the man is entitled to his freedom. He is released in one case, but before he can step out of prison, is entangled in another. These are all demonstrably mala fide prosecutions. The powers that be actually wish him to ‘apologise’ for publicly sharing his honest thoughts.

A less ham-fisted society may even have considered him for an advisory role in policy formulation, as he has experience few have, tragic as that has been. But no. The honourable black robes, whether knowingly or unwittingly, have been denying him his freedom. Had he been a politician seen as more ‘mainstream and not fringe’ would a different outcome have been possible?

Fundamental rights to me are inalienable. Nobody’s freedom should be curtailed on account of their views. But this principle needs to be applied across the board. Outrage and uproar can’t be selective. Nobody needs to be treated or made to feel like they are children of a lesser god. It can’t be simpler.

The writer is a former editor of Dawn.

abbas.nasir@hotmail.com

Published in Dawn, January 29th, 2023