CAN PAKISTAN HAVE ITS ‘SPUTNIK MOMENT’?

India is now only the fourth country in the world to successfully land on the moon. A few hours after the landing, a ramp lowered down and allowed a rover to wheel off on the lunar surface. All of this took place about 400,000 kilometres away from Earth. By any measure, this is an incredible achievement of engineering and science for our neighbour.

As expected, there have been different types of reactions in Pakistan. In the fastest jerking of the knee, some have declared the landing itself to be fake. Others have questioned the money spent on the space programme, insisting it should have instead been used to alleviate poverty in the country — although, it must be clarified, India’s space programme is astonishingly cheap.

But the most common reaction has been to ruefully reflect on the poor state of Pakistan’s own space agency, Pakistan Space and Upper Atmosphere Research Commission (Suparco). One of the more widely circulated memes in the aftermath of India’s moon landing compared the considerable scientific qualifications of the heads of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) with those of Suparco, which has been led by military personnel over the last two decades.

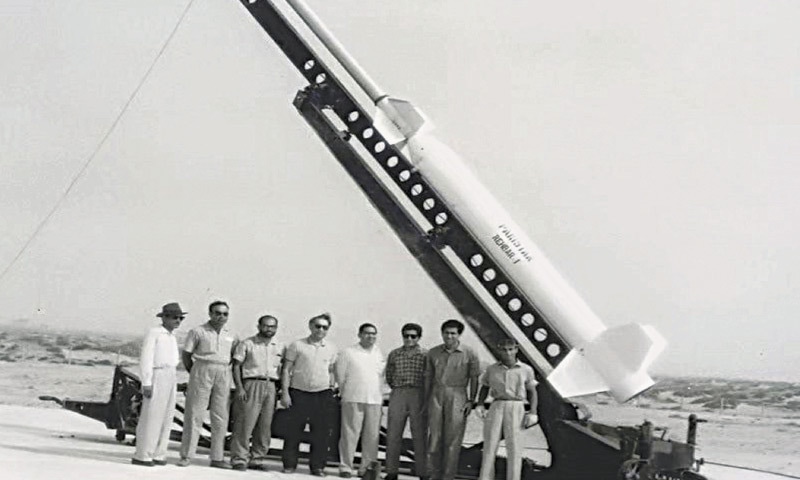

All of this becomes even more poignant due to the fact that Pakistan was an early participant in the space age. Suparco, founded in 1961 at the urging of the late Nobel laureate Professor Abdus Salam, was amongst the earliest space agencies in the world and had an active rocket programme in the 1960s.

Clearly, when it comes to space, things did not go well after that.

The success of India’s Chandrayaan-3 mission to the moon has forced many in Pakistan to look inwards and ask: why did Pakistan’s space programme fail to achieve the lofty ambitions that spurred its creation? And can we still breathe life into it?

Any conversation about Pakistan’s prospects in space justifiably leads to eye-rolls and jokes (some good ones too!). Space is not the only sector where Pakistan has seen a decline, and failures of state institutions are far too numerous to recount. Nevertheless, the reactions in Pakistan to Chandrayaan-3’s soft-landing on the moon shows that we do still care.

And that is, perhaps, something to build on.

Rediscovering Our Curiosity

Where do we even start? As most of the readers here know, there are serious shortcomings in almost all of our scientific and educational institutions. But instead of throwing up our arms, individuals can still respond and make a difference, even if that difference is small and only impacts people in their personal lives. Perhaps, for starters, one perfect response to Chandrayaan-3 would be to make a collective vow to be just a bit more curious.

This is something we are all capable of. The recipe for that is to simply ask questions. There are no ‘dumb’ questions.

When we look at the moon, why are some parts darker and some parts lighter? Why is the sun so hot? Why is the sky blue? What about the sky on the moon or Mars? Why do some planets have beautiful rings around them, and some don’t? Are there volcanoes on Mars? And perhaps more pertinent to Chandryaan-3, why is there interest among countries in going to the South Pole of the moon?

Some questions are easy and some are hard. There are no expectations to change the country. Instead, it is about rediscovering our innate curiosity, which is far more evident when we are young. Of course, many of you are already curious. But be more deliberative and mindful about it. Perhaps, set a day of the week to ask a question about space and astronomy, and then seek an answer. If you have children and/or nephews/nieces, involve them as well.

This is the first step. Finding the correct answer, an answer that is acceptable to most scientists, is itself challenging. A search on the internet can take you to strange places. But there are reliable sites, such as space.com or astronomy.com, that can provide good information. Wikipedia has also become quite good when it comes to basic sciences. There are limited resources in Urdu, but this is changing. For example, you can ask questions and find reliable answers at ‘Science Ki Dunya’ on Facebook.

This focus on individual curiosity might sound either too ‘self-help’-oriented or appears to be in the mould of neoliberal individualism. Neither is the intent here. Instead, this “ground-up curiosity” can lead to more conversations about space, astronomy and the sciences in general, and this can lead to an in situ demand for science museums, planetaria, and Urdu and other local language science programming on television.

This, in turn, may spur some kids to pursue careers in space-related fields, and may impact the space programme in 10 or 20 years from now.

The Other Space Race

But the elephant in the room is still there. What happened to Pakistan’s space programme?

After seven decades of rivalry and multiple wars, a comparison with India is inevitable. It is clear, by any measure, that the Indian space programme is light years ahead of Pakistan’s. It seems like the space race, if there ever were one, is already over. On the other hand, the Chandrayaan-3 landing may turn out to be a moment of change for Pakistan.

Ironically, it was another space race that gave Pakistan its head-start, helping it become only the third country in Asia, after Japan and Israel, to launch a rocket in space. On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union became the first country to launch a satellite, Sputnik 1, into space. It not only demonstrated Soviet superiority in science but it also instilled fear, as now an enemy satellite could be seen passing over the United States as well.

Caught off-guard, the US responded with a couple of decisions that proved vital for the future. First, the US created a public-facing National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Nasa) in 1958. Apart from defence and science, part of its mission was to build up hope and inspiration, and yes, propaganda as well. Second, also in 1958, through the National Defence Education Act (NDEA), the country embarked on improving maths and science education in schools.

The US knew that it was well behind the Soviet Union and it needed time to catch up. It was in this context that President John F Kennedy set the goal of going to the moon in 1962, with these famous words: “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”

It is clear, by any measure, that the Indian space programme is light years ahead of Pakistan’s. It seems like the space race, if there ever were one, is already over. On the other hand, the Chandrayaan-3 landing may turn out to be a moment of change for Pakistan.

It was this push for the moon that also led Nasa to Pakistan. The US agency needed information about the atmosphere from various parts of the world, including the Indian Ocean and the Arabian Sea. Pakistan, being a close ally, provided research support and helped launch a two-stage sounding rocket, Rehbar-1, in 1962, thus becoming only the third country in Asia, after Israel and Japan, to launch a rocket into space.

India was not far behind. It also helped Nasa collect data with a rocket launch in 1963. Indian space research at the time was conducted under the Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSOPAR), created in 1962, and was later superseded by ISRO, established in 1969. Thus, contrary to popular perception, Pakistan and India had a comparable start in the space age.

What Went Wrong?

The team assembled with the help of Salam and Suparco helped blossom Pakistan’s rocket programme throughout the 1960s, with further launches, including two hypersonic rockets, reaching close to 1,000 kilometres in the atmosphere.

This could have been a solid foundation for a public space programme, but the 1970s and the 1980s saw a shift in Pakistan’s policy towards the nuclear programme and the pursuit of the atomic bomb.

Space has always been associated with dual-use technology. The same technology that inspires many to dream about exploring the solar system can produce missiles that can carry weapons across continents. In fact, the real threat from the Sputnik-1 launch was perceived to be this missile superiority of the Soviet Union over the US. Similarly, there has always been a military aspect behind Nasa as well, and most of the astronauts in the 1960s came from a military background.

But the public aspect of the space programme is important as well. It can inspire a whole generation of scientists and explorers. Furthermore, public failures can lead to more scrutiny and generate pressure for making improvements.

Unfortunately, Suparco became an afterthought in the late 1970s and was almost defunded. It was re-established through a presidential ordinance in 1981 by Gen Ziaul Haq. Lip-service was paid to a public space programme, but much of the emphasis shifted towards military applications of space technology.

This shift continued under Gen Pervez Musharraf, when all space- and nuclear-related activities were placed under the National Command Authority (NCA) in 2000, and the succession of military personnel leading Suparco started.

In the meantime, the public space programme continues to be adrift. Suparco’s first satellite, Badr-1, was sent to space in 1990. In terms of technology, it was a modest satellite, and it was launched by China from the Xichang Launch Centre.

A follow-up, Badr-B or Badr-II, was launched in 2001, this time on a Russian rocket from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. The last two decades have seen a deepening of space ties with China, with the Chinese Space Agency launching Pakistan’s first communications satellite in 2011, and then a joint remote-sensing system in 2018.

In a welcome step, Pakistan did lay out a space strategy in 2014. It was first called Pakistan’s National Space Programme 2040, and has now been renamed Space Vision-2047.

Reviving Pakistan’s Space Programme

The state of Pakistan’s space programme is clearly not strong. But I do briefly want to address one question about space: can we afford to invest in space when there is so much poverty in the country?

This is an old argument from the space race during the Cold War era. It is now clear that having an effective space programme is essential, not only for a strong military, but also as an engine for economic growth. The need for satellites extends from monitoring floods and enemy troop movements to communication, internet, and the spread of education.

India has effectively shown that, with clever use of indigenous resources, this can be done successfully at a relatively low cost (at 0.04 percent, India is seventh in the world in its space spending relative to its GDP) with high dividends (the space economy of India is expected to grow to $10 billion by 2025).

In that context, an investment in space is a necessity, not a luxury.

Indeed, Pakistan has been making extensive use of international satellites for storm-tracking, weather, communications and agriculture. But the borrowing of data also creates its own significant costs, without building a significant infrastructure in the country. In crises, China has provided assistance from its military satellites. But Pakistan lags behind in the production of its own satellites, and the country still does not have the capacity to launch a satellite into space.

Given the history of Pakistan and India, it is tempting to make a case for investment in space through the lens of defence needs. The argument would be that, even though China has helped Pakistan in the past, a complete reliance on another country for defence may not be the best strategy.

But this will not only be ignoring the cautionary tale of Suparco’s own history but also missing the best spirit of space exploration. This may sound naïve (and sometimes you just have to go with idealism and naiveté), but space exploration has also given us images of Earth as a “blue marble” and “a pale blue dot.” When thinking about reviving our own space programme, we have an opportunity to aim for ideals higher than that of fighting with fellow human beings.

There are many things that are needed, but here are three broad thematic elements that can potentially help with the revival. These do not include an explicit discussion of education, as that is a large topic and a lot of ink has already been spilled on it.

1) Vision and Consistency: Meaningful changes take time. The key, however, is the consistency required over a long period of time. A public declaration of goals exerts at least some pressure of accountability. In a welcome step, Pakistan did lay out a space strategy in 2014. It was first called Pakistan’s National Space Programme 2040, and has now been renamed Space Vision-2047. It aims to create an infrastructure to locally build and launch geosynchronous (GEO) and low-Earth orbit satellites by the 2040s. While it is almost a necessity for Pakistan to build this capacity, these may not be the goals that genuinely inspire.

On the flip side, there was a plan to send an astronaut into space by 2022. Even after the delay, if and when it happens, it will get attention. The astronaut is expected to go to the Chinese space station on a Chinese rocket. It is unclear what kind of infrastructure development this will induce in Pakistan and the role it will play in Space-Vision 2047. This is an ambition without a strategy.

The goals have to have a sweet spot of lofty enough to inspire, but low enough that they are achievable. I know that simply shooting for the moon sounds extravagant. But Pakistan can make technical contributions in larger international collaborations. This directly leads to the next point.

2) International and Private Collaborations: The space sector is expanding in all spheres. There are now international collaborations sometimes involving tens of countries. There are certain areas, especially in engineering and the IT sector, where Pakistan can contribute to these collaborations in a cost-effective way.

Since there are many countries that can potentially fill this goal, the key thing here is to build meaningful connections. China, of course, is not only a close ally of Pakistan, but it is also one of the leaders in space.

In a welcome sign, a cubesat (a miniaturised satellite) from Pakistan, ICUBE-Q, is expected to be on board China’s 2025 Changé 6 sample return mission from the lunar South Pole. Earlier this year, Pakistan also sent seeds to the Chinese space station, Tiangong, for research into environmentally tolerant seeds. Similarly, Pakistan is exploring the possibility of a formal agreement to join both the Tiangong space station, as well as the more ambitious China-led base on the lunar South Pole.

If these collaborations can be used effectively to build local infrastructure for the public space programme, and do not simply serve as a continuation of the military alliance, then this can provide a reasonable platform for space development in Pakistan.

At the same time, it is crucial for Pakistan to look beyond China as well. There are some on-going collaborations with Turkey, and the UAE’s ambitious space programme may also provide opportunities for Pakistan.

This is also the time of a space start-up boom. These are companies that are taking the opportunity to provide products and services to the space industry. These can range from satellite technology and launch services to collecting and analysing data from satellites, creating materials suitable for space, building technology to clean up orbital debris, research on crops that can withstand high radiation, solar panels that can work on the moon, specialised software for satellites, and, for the rich, even something like space tourism. It is estimated that, by 2040, this could be a trillion dollar industry. In some ways, this is reminiscent of the IT boom of the 1990s and the 2000s. I will mention India again, not for competitive purposes, but rather to look at a successful model.

India has at least 140 registered space start-ups, and these brought in $130 million in investments last year. Following the success and publicity of Chandrayaan-3, this number is expected to at least double annually for the next couple of years.

One of the reasons for this boom was the establishment in 2020 of a new agency, the Indian National Space Promotion and Authorisation Centre (IN-SPACe), to facilitate friendly legislations towards the private industry.

There is, however, perhaps an unnecessary impediment. Pakistan is a signatory of all five major United Nations treaties on space. But in order for them to take effect, they have to be ratified by the country’s parliament as well. As far as I know, there are no philosophical or political objections to the treaties. Yet, in a perfect reflection of our space programme, these treaties have likely not been ratified out of indifference and a lack of priority.

Nevertheless, there is interest in space start-ups both inside and outside of Pakistan. There is a relatively new National Incubation Centre for Aerospace Technologies (NICAT) in Islamabad. Of course, Pakistan is not the only country with such incubators, but Pakistan produces a lot of engineers and computer scientists that may be suitable for the space industry.

If, like India, Pakistan can emphasise, facilitate and encourage private investment in this sector, we may see tangible growth in this sector. We may have some head start here, as there already are entrepreneurs in the Pakistani diaspora that are interested in such investment, and there are others who work in some of the leading space companies in the world.

3) Space in the Public Sphere: There is an immense power in the sense of awe and wonder. This is true for both individuals and the society at large. Apollo 11 captured the imagination of millions, and that led to a boost in science PhDs even after the funding support dried up.

Similarly, there is going to be a generation inspired by ISRO’s space missions to the sun and Mars, and especially with the successful landing of Chandrayaan-3 on the moon. It is hard to quantify such an impact — but impact there is.

Despite the doom and gloom, there is considerable public appetite for science, space and astronomy in Pakistan. Just look at the tens of thousands of people who show up for the two-day Lahore Science Mela (LSM) every October (scheduled to take place on the 28th and 29th this year). There are also some fantastic amateur astronomy groups in Pakistan, such as the Karachi Astronomers Society, the Lahore Astronomical Society (LAST), and Pak-Astronomers and Rah-e-Qamar (both located in Islamabad). They are thriving because of a public interest.

The problem is not a lack of interest. It is the paucity of places for public science.

This does not require an extensive space policy or the passage of a space legislation. The original idea of PIA planetariums, in Karachi, Lahore and Peshawar, was an inspired one. I, myself, was grateful to Karachi’s PIA planetarium when it opened in the early 1980s. It was magical to be transported to a sky full of stars, something that is not possible to see from the ‘City of Lights’. Unfortunately, both the Karachi and the Lahore planetaria fell into disrepair and are shells of their former selves.

Imagine, for a moment, a state of the art planetaria in all the major cities of Pakistan — a place where both children and adults could go to learn about science, space and astronomy. In places like New York and Chicago, a planetarium is a major tourist destination. Similarly, India has over 40 planetaria, with the Birla Planetarium in Kolkata being the second largest in the world.

In Karachi, there is a spectacular multi-storey Magnifiscience Centre, established by the Dawood Foundation. The astronomy and geology wing of the museum will open later this year. But already, it hosts observing nights in collaboration with the Karachi Astronomers Society. This is the type of public science and collaboration that can happen with a museum or a planetarium. Opportunities create more opportunities!

Similarly, there are at least two dozen channels that constantly have political talk shows every night. Almost all of these channels covered the news of Chandrayaan-3 landing on the moon. Some of these channels also spent time ruefully commenting on the lack of comparable space achievement in Pakistan.

Now, imagine just one of the channels dedicating itself to producing good quality science and space shows in Urdu (and other local languages) for both children and adults. This could well have a national impact 20 or 30 years down the line, or maybe not. But, if done right, it will still impact the lives of countless young people looking for, and being introduced to, the joys of space, science and the universe.

Looking to the Stars

Can any of this make an impact? I truly don’t know. I wouldn’t blame you for reading this article and thinking that this is simply wishful, unrealistic thinking. Our track record is abysmal. And yet, maybe, just maybe, this time it will be different.

There are many low-income countries like Pakistan, struggling to take care of even some of the basic needs of their citizens. But because of a historic rivalry with India, this moment has the potential to be a Sputnik moment for the country. Even if the critics are right and nothing changes, even then I hope that this is a Sputnik moment, at least for a few individuals.

Christopher Nolan’s science-fiction film Interstellar ends with Dylan Thomas’ famous poem, Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night. For our purposes, I shall cite a couple of lines from another Dylan Thomas poem from 1939, Being But Men:

Out of confusion, as the way is,

And the wonder, that man knows,

Out of the chaos would come bliss

That, then, is loveliness, we said,

Children in wonder watching the stars,

Is the aim and the end.

May we kindle our sense of awe. Ad Astra!

The writer is the founder of Kainaat Studios which produces high-quality astronomy content in Urdu. He is also Professor of Integrated Science and Humanities at Hampshire College, USA, and an astronomer affiliated with the Five College Astronomy Department (FCAD) in Massachusetts, USA

Published in Dawn, EOS, September 17th, 2023