Disney is celebrating its 100th birthday this month. It’s hard to imagine the studio enjoying such longevity without its strong musical legacy. Songs from recent Disney films, such as ‘We Don’t Talk About Bruno’ from Encanto (2021) or ‘Let It Go’ from Frozen (2013), have met with great success. But this has been a strength of the studio for much of the past 100 years.

Every decade since the 1930s, Disney has released landmark films featuring musical numbers that remain household favourites today. And the Disney “renaissance” in the 1990s was underpinned by musical stories and huge Broadway talent. Many of these films were subsequently adapted into long-running West End and Broadway musicals.

This musical legacy extends right back to the studio’s first sound film, Steamboat Willie (1928). Before this, Disney was just one of many competing animation studios. Utilising the new technology of synchronised sound to make Mickey Mouse talk and sing made a huge star of the character — and established Disney as the leading animation studio.

Music in the silent era

But what about the first five years of the studio between 1923 and 1928? This was the “silent” era of cinema, when films didn’t have soundtracks, but were usually accompanied by a local organist or pianist beyond the control of the studio.

Disney films have always been musical — even in the silent era

Surprisingly, these earliest Disney films didn’t avoid references to sound. The Alice Comedies (1923-1927) and Oswald the Lucky Rabbit series (1927-1928) the studio made in this period were deeply musical.

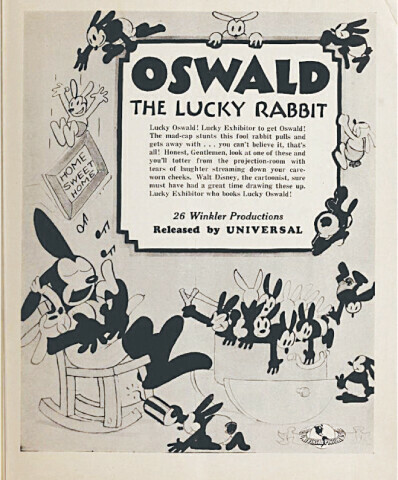

This early launch advertisement for the new Oswald series from 1927 highlights this musicality. Oswald is shown whistling, with musical notes rising from his mouth.

This was a consistent way sound and music were evoked in these early cartoons, often alongside the characters singing or playing music. The first Alice Comedy, Alice’s Wonderland (1923), features a three-piece cat band playing for Alice. Musical notes rise from their instruments while two other cats dance to the music.

The first Oswald cartoon produced, although only released later, was Poor Papa (1927). It similarly features several musical sequences, where graphical notes signified the presence of music.

Onomatopoeic musical words were commonly used, such as a “zzz” indicating the snoring of sleeping characters, a “kiss” or “smack” directed between amorous lovers or the “ouch”, “yow”, or “eee” of characters being hit.

These are complemented by similar graphic-word phrases emitted by inanimate objects, where the source has no capacity for language and the word is clearly intended as an evocation of a pure sound. Repeated examples of this include the “clang clang” or “toot toot” of a train, the “honk honk” of a car horn, the “ding dong” of bells ringing or the “pop” or “bang” of guns.

Animated cartoons in the silent period were very self-reflexive and brought attention to themselves as drawn constructions. As a result, their onscreen musical notation often became integral to gags.

In Alice the Whaler (1927) a parrot eats rising musical notes as if they were grapes. Meanwhile in Alice the Fire Fighter (1926), a pianist saves a group of mice from a burning building as the rising music notes form a stairway for the victims to escape.

In Rival Romeos (1928) Oswald attempts to serenade his love, but is thwarted in a series of music-related gags. This includes rising musical notes turning into stick people who begin to fight, and a goat eating his sheet music. That gag is repeated almost identically in Steamboat Willie, indicating the continuity between silent and sound eras.

Pop songs and pop stars

In addition to these general musical elements, many of the silent Disney cartoons directly reference popular hits of the time. Poor Papa, for example, is an unofficial adaptation of a 1926 hit song of the same name. Both the cartoon plot and song lyrics feature a father comically overburdened with children.

Pop songs and stars have featured in recent Disney films, such as Shakira’s number in Zootropolis (2016) or the David Bowie-esque “Shiny” in Moana (2016). But this happened much further back in the studio’s history, too.

Popular music references in silent Disney films served as cues for the live musical accompaniment that would have been featured in cinemas in this period. Musicians would use dedicated special effects devices or “traps” to recreate the onscreen “bangs” and “crashes”, while organs came with built in “stops” for amusing music and sounds.

Skilled musicians could enhance the comedic effect by playing recognisable songs whose lyrics and title might produce an ironic commentary, a technique known as “kidding”, “funning”, or “burlesquing”.

There is even evidence that audiences would have been invited to sing along with popular songs — a far cry from our modern expectations of silence in the cinema. This is, however, in keeping with Disney singalong versions of their hit films at theme parks and on Disney+.

The next major Disney animation film, Wish (due to be released in November 2023) looks likely to continue this tradition and have audiences singing well into the company’s second century.

The writer is an associate professor in film studies at the University of Southampton in the US

Republished from The Conversation

Published in Dawn, ICON, November 19th, 2023

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.