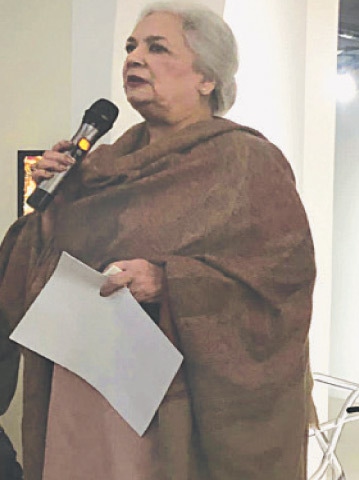

LAHORE: It was the launch of the latest edition of The Aleph Review, one of the regular prime literary journals in English language in the country, but it turned out to be a sort of tribute to the late Pakistani-British author Sara Sulehri, courtesy Prof Navid Shahzad. In the event at the Como Museum of Art in Gulberg Ms Shahzad remembered the late author and her friend who had been featured in the latest edition of the journal too.

“I was a few years older than Sara when I was teaching at the Department of English Language and Literature at the Punjab University. Her mother, Mair (Jones), a Welsh woman, was my colleague.”

She called Sara unusual in many ways, saying that in her class assignments, Sara never indicated the kind of seismic shift that was seen in her writing later on. Sara would sit silently through the class listening to Navid Shahzad teach Hamlet and Othello. Calling her unreservedly courageous, she said Sara was the first in the class who had seen the latent passion that Iago had for Othello and there was dead silence in the class.

“She and I started off immediately because we both were voracious readers and would often exchange books, using her mother as a conduit.”

Talk at The Aleph Review launch turns master class for women writers

Talking about the Meatless Days, for which Sara Sulehri is mainly known in Pakistan more than her other works, Navid said the book could not be classified as a memoir in totality as there were her radical opinions in it that she had written down in an extraordinary language.

“Sara and I both shared a love for theatre and teaching drama brought us closer.”

Navid referred to the four characters in the book that stood out for their characterisation, including Sara’s eccentric Dadi; her mother Mair, the second wife of Z.A. Sulehri, trying to fit in a very conservative household with a right-wing husband; Iffat, the beauty of the family and little Irfan, born with an asthmatic condition. To her, Sara recorded bravely one of the messiest periods of Pakistan’s history.

She remembered the last meeting with Sara when both of them were dealing with the deaths in their families.

Besides Sara Sulehri, Navid Shahzad spoke about the spirit of women writers.

“Publishers often define women literature as the writings done by women, which to my mind, is very reductive attitude as after all, nobody talks about men’s literature, which is a talk about literature per se.”

She said Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own would be often considered as the driving force behind the movement, arguing for the necessity of metaphorical and literal room for women’s literature in the literary tradition. Women’s writing has a history of being much ignored due to the inferior position that women hold in the male-dominated societies like ours, yet despite this discriminatory attitude, the subcontinent itself has an ample share of world class writings by women.

In the pantheon of English writers from Pakistan besides Sara, she mentioned Bapsi Sidhwa, Muneeza and Kamila Shamsie, Uzma Aslam Khan and Fawzia Afzal-Khan.

“Never forget that we women are historians. Majority of women live their lives between the binaries of quiescent ductility and noise of increasing intrusive volume, which threatens to silence them at every juncture.”

Navid Shahzad had some suggestions to women writers as she said, “All you women, relish your feelings, turn them over like you would fry an omelette, coax them into a new shape. That’s a challenge for you because women have a particular and very complex relationship with language. They have been barred for long from acting on their own ambitions altogether as they have had to turn to language as a way of dealing with and influencing the world. We write because we want to hear ourselves to know that we have shared experiences”.

She said when women would sit down to write, they would do it for reasons alien to male writers and that the women’s writings had been linked to acknowledgement of validity of the female experience.

Artist Rashid Rana, who designed the cover of The Aleph Review, discussed with Aasim Akhtar his transliteration series. He said he would take an image from a different time or place like from 17th century and dissect it into smaller digital fragments and reassemble it to evoke a sensibility of another image from another time. “It’s almost like an act of visual transliteration across time and region which he enjoyed a lot.”

His cover for the Aleph Review is also a part of his transliteration series. Regarding the series, he said one would look at the macro and micro at the same time. About the shift from 2D to 3D, Rana said it never happened. “I have three dimensional works but deep down I am a painter. I have been fascinated by the idea of two-dimensionality because throughout the human history, from cave paintings until now, there has been so many ways of engagement with two-dimensional surface. Two-dimensionality, in absolute sense, does not exist in nature but humans have been engaged in creating two dimensional surface.”

Hassan Tahir Latif, the managing editor of The Aleph Review, said, “Currently we are accepting works specifically from the people who come from the conflict zones or who are from diverse backgrounds, facing oppression”.

He said each volume of the review had a theme and the submissions were directed towards that theme. “This year’s theme is spirit in its all its permutations.”

Kanza Javed, Faizan Aslam, Nadia Amir read out pieces of their writings that are a part of the review.

Published in Dawn, December 23rd, 2023