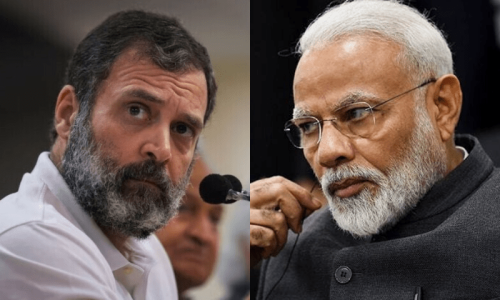

IN the end, the bluster of Ram temple could not lift Narendra Modi’s spirits and he had to turn to Nitish Kumar for help. The chief minister of Bihar is a crucial former ally-turned-opposition satrap. He returned last week to the BJP’s corner hoping to stabilise Modi’s boat of unabated ambition. In the process, he ditched the opposition alliance.

Modi’s inability to pouch divine blessings for communal polarisation wasn’t unexpected. The dog whistle was still needed. Defiling churches and vandalising crosses sent out the signal. There was a need to ransack a Mughal-era mosque in Agra protectively, and to raise slogans targeting other relics of India’s Muslim past.

The communal powder needed to be kept dry. The peace call from the new temple’s pulpit seeking to usher the Hindu utopia of Ram Rajya had not enthused the opposition, comprising a bulk of 63 per cent voters who didn’t bat for the BJP in 2019. Even the grand Shankaracharyas failed to bless the event, with at least one of them calling it a political show.

The event did seem overplayed, and destined to be no more than media hamming. Reports abound of lucrative land deals ringing the city, which now has an airport of its own. Religious polarisation around Ayodhya, moreover, has been milked dry and might not be the potent brew again. Other avenues must be explored.

There’s an Indian saying that a closed fist is worth a hundred thousand gold mohurs or something as valuable. Opened, it loses the mystique, “it becomes worthless dirt”. It’s what may have happened at the temple to a revered pomp-shunning deity. Well-heeled men and women showed up in Ayodhya no doubt. But that by itself could hardly claim to define the electoral logic of a complex country in need of jobs, food security and, if possible, scientific education in backward states where the BJP is strongest.

On all previous occasions, a divided opposition stood pulverised. That looks different for the 2024 contest.

Indians see Lord Ram as a shield against adversities, as a healer, not as a jewel-bedecked deity he was inaugurated as. After the mystery was buried in the rubble of the Babri Masjid, a mystery woven around falsified history, blind faith and misquoted judicial verdicts, there was at least the illusion of divinity working for the BJP. In the opulent temple built on the rubble, the illusion disappeared. Everyone saw the prime minister looking busy keeping the cameras studiously focused on himself.

Seen with more concern for facts, Mr Modi’s two previous triumphs, in 2014 and 2019, resulted from earthy elements far removed from the religious fervour he hoped to produce in Ayodhya last week. In pre-independence communalism, the two sides used slaughtered cow and pig heads to lure rival responses.

In post-independence mobilisations, the cost-effective and more high-yield method is rumour-mongering. Rumours of Muslims attacking a train coach packed with Hindus was mined to catapult Mr Modi to the crucial local post in Gujarat, which became the launching pad for his higher orbit. Rumours of a Hindu girl’s molestation, though it proved to be a contrived falsehood, burnt down Muzaffarnagar to polarise Jat Hindus in 2014. The Jats have since rowed back.

In 2019, claims of an aerial sortie using ‘cloud cover’ to bomb an alleged cross-border terror hub to avenge the killing of 40 paramilitary men in Pulwama whipped up a nationalist froth to skim votes from. On all previous occasions, a divided opposition stood pulverised. That looks different for the 2024 contest. The INDIA allies are savvier in guarding their turf. It’s an asset but also a challenge.

It so happens that India’s political cookie is baked from caste and regional interests. Kumar’s departure could be a setback for the anti-Modi grouping, but it has its own contradictions. In the 2014 elections, Nitish Kumar wasn’t a Modi ally when the BJP won 22 of Bihar’s 40 seats, and Kumar got just two.

In 2019, allying with Kumar’s party the BJP’s toll dwindled to 17 seats, and Kumar got 16. His gain is not necessarily to the BJP’s advantage. The equation may thrive on perversion, more likely, by affecting the optics adversely for INDIA. Else, Bihar is not done and dusted yet.

On the contrary, the BJP with Shiva Sena won 42 seats of Maharashtra’s 48 last time. That alliance collapsed. The Congress-Shiv Sena-NCP grouping against Modi could damage the BJP more than he can afford. In Punjab, the BJP-Akali alliance won six of 13 in 2014 and four in 2019. The snapped Akali Dal alliance has been further buried by the killings of Sikhs abroad. From Jammu and Kashmir, the BJP uncannily won three of the six seats last time. Clearly, the BJP would have to excel itself on most fronts against a prepared opposition.

This is where the Congress needs to do damage control and make Mamata Banerjee feel more secure as a bulwark in West Bengal. In fact, it’s the only state where the opposition needs to work hard to cement its alliance. Facts on the ground could guide the way forward.

In 2014, the BJP won two seats of the state’s 42. Banerjee won 34. But in 2019, the BJP’s tally jumped to 18 seats, and Banerjee was down to 22 with 43 per cent votes and BJP coming menacingly at 40pc. Congress got two seats from 5.61pc votes and the CPI-M with 6.28pc couldn’t get a single MP. Banerjee has offered the two seats to the Congress.

What should the allies do? Currently, it’s their unrealistic demand for a greater number of seats that threatens the alliance. The Congress and CPI-M both assert they must save the constitution. Would they do the right thing then, or play party politics and let the country and the constitution be damned, potentially forever, no different from Nitish Kumar?

The writer is Dawn’s correspondent in Delhi.

Published in Dawn, January 30th, 2024

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.