SHAMBHU: Protesting Indian farmers relaxed inside their tractors on Thursday as they awaited orders from leaders to advance on the capital, vowing they’d last longer than the police currently blocking their route.

“We are here for the long haul,” said Mela Singh, a 70-year-old from Punjab state’s Mansa district, one of the thousands of farmers setting up camp on the highway after their column was stalled by roadblocks about 200 kilometres north of New Delhi.

“A month, six months, a year, it does not matter, we will only retreat when we win this battle.” Community kitchens and makeshift medical clinics have been established, while other farmers snooze beneath tarpaulins stretched over their tractor trailers.

Thousands of farmers this week launched what they have dubbed “Delhi Chalo”, or “March to Delhi”, to demand a law to fix a minimum price for their crops, in addition to other concessions including the waiving of loans. The demonstrations come ahead of national elections likely to start in April.

They echo ones in January 2021, when farmers used their tractors to smash through barriers and rolled into New Delhi on Republic Day during their then year-long protest.

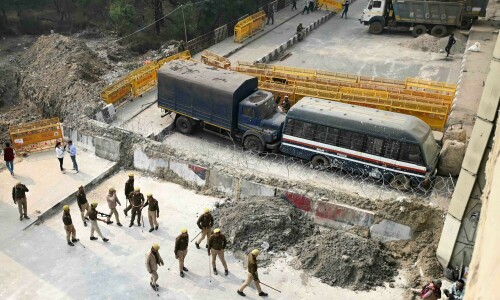

This time around, their hundreds of tractors have been halted by fearsome police barricades of concrete blocks, rolls of razor wire and barrages of tear gas when the farmers come too close.

But the tense initial energy of the protest — marked by sloganeering and farmers using kites to ward off police drones dropping tear gas from the air — has given way to a more languid wait.

‘Everyone’s fight’

The protesting farmers are in no hurry to head back home. Kamaljit Singh, 35, insisted everyone had a cup of the super-sweet milk tea he had on offer.

“We have 100 litres (22 gallons) of milk,” said Kamaljit, a farmer from Punjab’s Patiala district, saying his village had gifted the milk to support the protest.

“Another 200 litres are on their way. We have enough for everyone.” The milk is a symbol that all are behind the protest, he said.

“Every person from the village has contributed,” said Kamaljit. “This is everyone’s fight.” Two-thirds of India’s 1.4 billion people draw their livelihood from agriculture, accounting for nearly a fifth of the country’s GDP, according to government figures.

Nearby villages are making sure the protesters are well fed, drawing from the Sikh tradition of “langar”, or community kitchen, and coordinated from village gurdwaras, Sikh places of worship.

“In every village in the vicinity, gurdwaras have set up community kitchens where food is prepared round the clock for the farmers,” said Sukhpal Singh, 63, also from Patiala.

Published in Dawn, February 16th, 2024

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.