It was somewhere in the fall of 2021, when I first came across a flyer for a workshop on mathematics for kids between the ages of six and 16. The email was from a faculty member of the Lahore University of Management Sciences (Lums), where I had been working as a communication professional for a few years.

I was never keen on numbers, and my daughter, who was 10 at that time, was exhibiting a similar lack of interest in the subject that, I later realised, was a key part of everyday interaction. A quick chat with Dr Imran Anwar, who was leading the workshop, convinced me to attend it with my unwilling daughter.

Once there, her reluctance quickly changed to curiosity as she joined a group tackling a tricky challenge.

FOLDING PAPER TO THE MOON

A trainer had distributed A4 sheets to students divided into small groups, with the instruction that: “Anyone who can fold the paper 10 times will be given a gift.”

Each group tried, but hit a roadblock at the eighth fold. One student even asked for a tissue paper and said he could do it with it. Another asked for a newspaper. But still, they failed.

For many people, maths anxiety is real. Now, a professor at Lums has introduced the idea of Maths Circles, a fun and simple solution to help young students overcome their fear of numbers and formulae

“Strange, isn’t it!” commented the teacher. Yes, obviously, but why? All those present in the room, including a couple of parents like myself, were perplexed and wished to know the answer.

The instructor built up on the exercise to introduce the ideas of exponential growth and infinity. He explained how there is a sequence that exists and how an A4 sized sheet with 42 folds (not possible physically) would be equal to the distance between the Earth and the Moon.

He explained that the Moon is the closest natural object to Earth, with an orbital distance range between 356,000 to 407,000 km.

A plain A4 sheet on paper, on the other hand, is approximately 0.1 mm thick. The thickness doubles with each fold. Fold it once, twice, and then three times, and it becomes 0.2, 0.4, and then 0.8 mm thick. After 10 folds, its thickness increases by a factor of 1,024.

After 20, 30, and 40 folds, the paper becomes over a million, a billion, and then a trillion times thicker than the original. At 42 folds, it equates to a thickness of approximately 439,804 km: enough to reach the Moon.

In mathematical terms, this type of growth is called exponential because the equation to model this is 2^n, which is some number (in this case the number 2) raised to an exponent (n).

In other words, you multiply the layers by 2 each time you fold. With each fold, you double the layers of paper you had in the previous fold. In other words, you multiply the layers by 2 each time you double the thickness of the fold.

“When we can’t do something practically, mathematics gives you the power to solve and explain it,” says Dr Anwar, who is an associate professor and heads the mathematics department at the Syed Babar Ali School of Science and Engineering at Lums. “This is the power of maths!”

THE ANXIETY IS REAL

The puzzles, games and challenges involving numbers invigorated my daughter’s interest in a subject that she had always approached with trepidation. This is something, Dr Anwar explained, that many students suffer from.

“Maths anxiety is real,” he emphasises. “This is why activities like our Maths Circles are important to help students overcome that anxiety.”

The testimonies from students show that Dr Anwar is on the right track.

“I don’t get excited about numbers and formulas and also struggle with memorising all the rules and equations involved,” says Masoom, a grade-school student who attended one of the workshops at the university. For him, it was the realisation that maths could be fun and easy that changed his attitude towards the subject. “The instructors made it very easy to understand concepts of the pigeonhole principle, graphs, and different theories based on experimentation and activities,” he adds.

WHOLESOME ENGAGEMENT

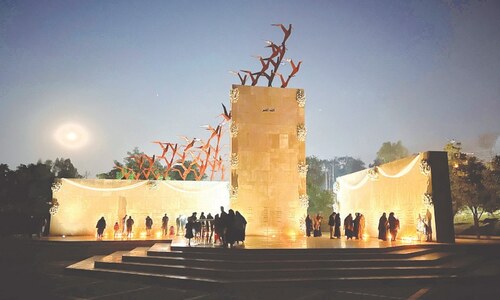

Since the first workshop in September 2021, there have been around 100 such circles, including 60 that were held outside the university.

Dr Anwar says the workshops are held on alternate weeks, with more and more schools interested in the activity. One session can vary from 60 to 90 minutes in duration.

The topics and activities for no two classes have been the same so far. A circle is conducted by two teachers, so that the students do not get the impression of a routine lecture, with two instructors making it more interactive.

Parents are also allowed to take part in these sessions. Sometimes they get involved and have fun with the kids.

From the very first day, there has been no restriction on the type of school or the social strata the kids belong to. No registration fee is charged from the participants. Instead, each participant gets a participation certificate with a box of doughnuts (an important mathematical shape).

“Since the students belong to grades six to 12, we keep the teaching style very engaging, easy to comprehend and bi-lingual, so no one feels left out,” continues Dr Anwar. This includes discussion on historical aspects as well. “For instance, we could discuss how Al-Beruni used trigonometry to calculate the diameter of the Earth.”

THE MULTIPLIER EFFECT

The popularity and success of the intervention has seen more and more teachers, including faculty members of other disciplines, volunteering as trainers. This is how the Maths Circles team was able to add outreach activities.

Now, faculty and graduate students visit schools in low-income neighbourhoods across different cities and conduct classes. These circles offer an alternative approach to teacher training, equipping educators with valuable insights and techniques beyond traditional methods, says Dr Anwar.

The Lums team have conducted such sessions at educational institutes outside the province as well, with circles held at institutes in the federal capital as well as the four provinces. Students from one school in Nankana Sahib, located around 75 kms from Lahore, have travelled to Lums thrice to be part of the activity.

Dr Waqas Ali Azhar, who serves as the Maths Circles’ coordinator, has been actively involved in introducing the activity to government and trust schools across Pakistan.

“We are breaking down the barriers of social disparity and ensuring that every child, regardless of their background, has access to the same opportunities to enhance their mathematical skills,” says Dr Azhar, who is an adjunct faculty member at the university.

‘EUREKA’

Dr Anwar stumbled on one such Maths Circle while he was with the Department of Mathematics at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, Canada. On inquiring about it, he was invited to sit through a class.

“Within the first five minutes, I realised it was something I wanted to replicate in Pakistan,” he tells me.

For him, it was shocking that the instructor, who worked in the area of analysis, had picked a technical theorem, and chopped it into small steps in the form of a worksheet, just like a game.

“All of a sudden, he gave an exceedingly difficult question based on applying that theorem, which most university students would not be able to answer,” continues Dr Anwar. “But that group of young kids did it,” he exclaims.

After the session, he made a beeline for the office of the director of the Maths Circle, one Dr Mayada Shahada. He signed up for the next class and ended up accompanying the team to a regional school.

There, he got the chance to see the schools and learnt first-hand about the structure and flow of these workshops. During the same visit, he got the opportunity to conduct a circle in a class and thoroughly enjoyed it.

Upon his return to Pakistan, Dr Anwar floated the idea at an institute mainly dealing with research and graduate teaching in mathematical sciences. It was, however, shot down, since the institute’s leadership believed that it did not match their research ideology.

Later, upon joining Lums in 2021, he floated the idea again and found a receptive audience in fellow faculty members.

The student body assisted the initial efforts, including preliminary research and mapping.

Dr Anwar remains committed to making these Maths Circles a permanent and recurring feature on campuses across Pakistan. His efforts have attracted the support of the Pak Alliance for Maths and Sciences, an advocacy group that focuses on the interests of Pakistani students.

He says several government officials as well as vice chancellors have expressed an interest to host these workshops and establish Maths Circles at their institutions.

For him, it remains a simple and effective way to spread the love of numbers.

The writer is a communications professional, who has been associated with Lums for the last seven years. She can be reached at khuzaimaazam1@gmail.com

Published in Dawn, EOS, March 17th, 2024

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.