India’s six-week election juggernaut resumed on Friday with millions of people lining up outside polling stations in parts of the country hit by a scorching heatwave.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is widely expected to win a third term in the election, which concludes in early June.

But turnout in the first round of voting last week dropped nearly four points to 66 per cent from the last election in 2019, with speculation in Indian media outlets that higher-than-average temperatures were to blame.

Modi took to social media shortly before polls re-opened to urge those voting to turn out in “record numbers” despite the heat.

“A high voter turnout strengthens our democracy,” he wrote on social media platform X. “Your vote is your voice!”

The second round of the poll — conducted in phases to ease the immense logistical burden of staging an election in the world’s most populous country — includes districts that have this week seen temperatures above 40 degrees Celsius.

India’s weather bureau said on Thursday that severe heatwave conditions would continue in several states through the weekend.

That includes parts of the eastern state of Bihar, where five districts are voting on Friday and where temperatures more than 5.1 degrees Celsius above the seasonal average were recorded this week.

Karnataka state in the south and parts of Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state and heartland of the Hindu faith, are also scheduled to vote while facing heatwave conditions.

Earlier this week, India’s election commission said it had formed a task force to review the impact of heatwaves and humidity before each round of voting.

The Hindu newspaper suggested the decision could have been taken out of concerns that the intense heat “might have resulted in a dip in voter turnout”.

In a Monday statement, the commission said it had “no major concern” about the impact of hot temperatures on Friday’s vote.

But it added that it had been closely monitoring weather reports and would ensure “the comfort and well-being of voters along with polling personnel”.

A wave of exceptionally hot weather has blasted South and Southeast Asia, prompting thousands of schools across the Philippines and Bangladesh to suspend in-person classes.

The heat disrupted campaigning in India on Wednesday when roads minister Nitin Gadkari fainted at a rally for Modi in Maharashtra state.

Footage of the speech showed Gadkari falling unconscious and being carried off the stage by handlers. He later blamed the incident on discomfort “due to the heat”.

Years of scientific research have found climate change is causing heatwaves to become longer, more frequent and more intense.

Gandhi seeks mandate

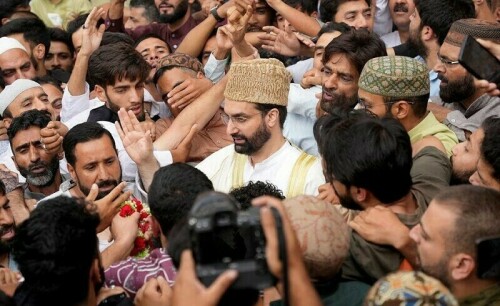

Friday will also see voting in the constituency of India’s most prominent opposition leader — Rahul Gandhi of the once-dominate Congress party.

The 53-year-old is fighting to retain his seat in the southern state of Kerala, a stronghold for opponents of Modi’s Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

“It is the duty of every citizen to become a soldier of the constitution, step out of their homes today and vote to protect democracy,” he wrote on X.

Gandhi is the son, grandson and great-grandson of former prime ministers, but his Congress party has suffered two landslide defeats against Modi in the last two general elections.

Gandhi has been hamstrung by several criminal cases lodged against him by BJP members, including a conviction for criminal libel that saw him briefly disqualified from parliament last year.

The opposition alliance has accused Modi’s government of using law enforcement agencies to selectively target its leaders and undermine its campaign.

More than 968 million people are eligible to take part in India’s election, with the final round of voting on June 1 and results expected three days later.

India’s top court declines to order any change to vote-counting process

Meanwhile, India’s Supreme Court declined to order any change to the vote-counting process, rejecting petitions seeking a return to the ballot system or to tally all paper slips generated as proof of voting for votes recorded by electronic machines.

“Blindly discussing any aspect of the system can lead to unwarranted scepticism and impede progress,” Justice Dipankar Datta said, after the two judge-bench delivered a unanimous verdict.

“Instead, a critical yet constructive approach guided by evidence and reason should be followed to make room for meaningful improvements and to ensure the system’s credibility and effectiveness.”

India has been using Electronic Voting Machines (EVM) since 2000 to record votes. The ballot unit is connected to a VVPAT or ‘voter verifiable paper audit trail’ unit which produces a paper slip that is visible to the voter via a transparent screen for about seven seconds before it gets stored in a sealed drop box.

Under the present system, the poll body counts and matches the VVPAT paper slips at five randomly selected polling stations in each state legislative assembly constituency, several of which are combined to form one parliamentary seat.

Critics and watchdogs, including some political parties, want verification to be done at more booths to increase transparency.

The Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), a non-government civil society group, petitioned the top court seeking verification of all EVM votes with VVPAT slips.