Polls opened in Iran on Friday for a run-off presidential election that will test the clerical rulers’ popularity amid voter apathy at a time of regional tensions and a standoff with the West over Tehran’s nuclear programme.

State TV said polling stations opened their doors to voters at 8am local time (0430 GMT). Polling will end at 6 pm (1430 GMT), but are usually extended until as late as midnight. The final result will be announced on Saturday, although initial figures may come out sooner.

The run-off follows a June 28 ballot with historic low turnout, when over 60 per cent of Iranian voters abstained from the snap election for a successor to Ebrahim Raisi, following his death in a helicopter crash. The low participation is seen by critics as a vote of no confidence in the Islamic Republic.

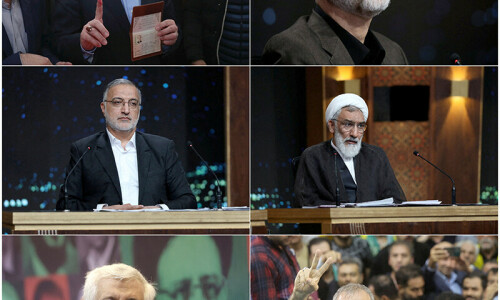

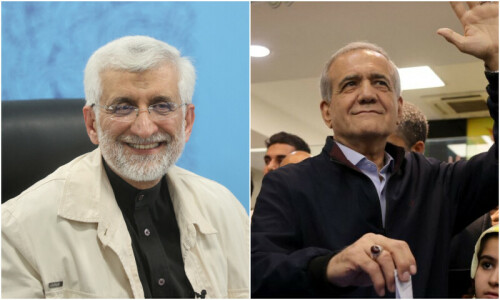

The vote is a tight race between low-key lawmaker Masoud Pezeshkian, the sole moderate in the original field of four candidates, and hardline former nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili.

While the poll will have little impact on the Islamic Republic’s policies, the president will be closely involved in selecting the successor to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s 85-year-old supreme leader who calls all the shots on top state matters.

“I have heard that people’s zeal and interest is higher than in the first round. May God make it this way as this will be gratifying news,” Khamenei told state TV after casting his vote.

Khamenei acknowledged on Wednesday “a lower than expected turnout” in earlier voting, but said, “it is wrong to assume those who abstained in the first round are opposed to the Islamic rule”.

Voter turnout has plunged over the past four years, which critics say shows support for the system has eroded amid growing public discontent over economic hardship and curbs on political and social freedoms.

Only 48 per cent of voters participated in the 2021 election that brought Raisi to power, and turnout was 41pc in a parliamentary election in March.

The election coincides with escalating regional tension due to the conflict between Israel and Iranian allies Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon, as well as increased Western pressure on Iran over its fast-advancing nuclear programme.

“Voting gives power …even if there are criticisms, people should vote as each vote is like a missile launch (against enemies),” Iran’s Revolutionary Guards Aerospace Commander Amirali Hajizadeh told state media.

The next president is not expected to produce any major policy shift on Iran’s nuclear programme or change in support for militia groups across the Middle East, but he runs the government day-to-day and can influence the tone of Iran’s foreign and domestic policy.

Faithful Rivals

The rivals are establishment men loyal to Iran’s theocratic rule, but analysts said a win by anti-Westerner Jalili would signal a potentially even more antagonistic domestic and foreign policy.

A triumph by Pezeshkian might promote a pragmatic foreign policy, ease tensions over now-stalled negotiations with major powers to revive the nuclear pact, and improve prospects for social liberalisation and political pluralism.

However, many voters are sceptical about Pezeshkian’s ability to fulfil his campaign promises as the former health minister has publicly stated that he had no intention of confronting the powerful security hawks and clerical rulers.

Many Iranians still have painful memories of the handling of nationwide unrest sparked by the death in custody of a young Iranian-Kurdish woman Mahsa Amini in 2022, which was quelled by a violent state crackdown involving mass detentions and even executions.

“I will not vote. This is a big NO to the Islamic Republic because of Mahsa (Amini). I want a free country, I want a free life,” said university student Sepideh, 19, in Tehran.

The hashtag #ElectionCircus has been widely posted on social media platform X since last week, with some activists at home and abroad calling for an election boycott, arguing that a high turnout would legitimise the Islamic Republic.

Both candidates have vowed to revive the flagging economy, beset by mismanagement, state corruption and sanctions reimposed since 2018 after the US ditched Tehran’s 2015 nuclear pact with six world powers.

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.