When Pakistan’s assistant coach, Azhar Mahmood, was brought to the media centre for the post-match duties, he admitted that the pitch did not behave as his camp expected.

He was not speaking to the media amid a match being played in another country, rather he was perched on the head table in his own country and in his hometown of Rawalpindi, where he has played cricket all his life.

The next day, Pakistan’s premier fast bowler, Naseem Shah, made no secret of his disillusionment with the pitch.

He was promised a spicy surface.

Unlike the last two seasons when he could see a shaved, bright yellow surface getting prepared during Pakistan’s pre-match training session, the fast bowler was welcomed with a lush green surface whenever he arrived at the Pindi Cricket Stadium ahead of the first Test of the season against Bangladesh.

Before the start of this match, which was the first Test in a string of seven Tests across the next four months, Pakistan made great efforts to establish a narrative that they wanted to play an exciting brand of cricket and they planned to achieve that by empowering their fast bowlers with conditions in which they could wreak havoc.

Such was the reliance on the method that they sent their only specialist spinner in the squad to play a first-class for Pakistan Shaheens against their Bangladeshi counterparts and announced, two days out from the match, that they would field a four-man pace attack.

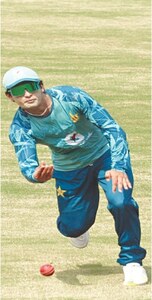

Naseem and his fellow fast bowlers, despite all the team management’s efforts to tailor the surfaces according to their wishes, ended up bowling 705 balls in the first innings across the second, third, and fourth day of the match.

Pakistan’s fast bowlers never had to bowl this many delivers in home Tests (including those played in the United Arab Emirates) in the last 22 years.

That the Rawalpindi surface was going to assist the fast bowlers all five days was always contentious.

August is not a suitable month for long-form cricket and that is why Pakistan’s domestic season usually begins in September.

They have hosted Tests in this month only twice before — in 2001 and 2003 — also against Bangladesh.

That heat and humidity were going to have their say in how the pitch was going to behave and when the pitch started to flatten out by the second day’s play, it was evident that Pakistan had gotten their entire game plan wrong.

In his post-match conversation, Pakistan captain Shan Masood mentioned how the team’s plans went awry because of a delayed start to the Test, which allowed the pitch to be sunned as the groundstaff dried a wet patch near the media centre.

When asked about the absence of Abrar Ahmed from the line-up, as seven of the nine Pakistan wickets to fall on the last day went to the spinners, he unveiled that the team management did not expect the match to stretch into the fifth day.

The conversation underscored that Pakistan had planned their entire strategy only around the first session of day one. They expected their pacers to floor Bangladesh on a spicy wicket under a heavy cloud cover, forgetting that the toss could have gone either way, as it did.

Long-form cricket can be the most complex format. With the conditions and the ball altering as the match progresses, the batting and bowling sides have to pre-empt. But, the bottom line is that the team that bags 20 wickets mostly ends up on the winning side, as Shan had highlighted on the eve of this match.

Home teams lay great emphasis on providing the best possible conditions to their bowlers to thrive. India and Bangladesh prepare rank turners to floor the opposition, while South Africa, England, New Zealand, and Australia prepare surfaces conducive to fast bowling.

Pakistan has struggled to pinpoint the formula for their success at home, underscored by the fact that their winless streak — dating back to February 2021 — has stretched to nine matches that have five losses. The most recent was against a presumably weaker opposition in Bangladesh who registered their first-ever Test win against Pakistan and their only seventh away from home.

In conditions conducive to fast bowling, captains call on fast bowlers throughout a Test innings.

They are expected to swing the new ball, seam it when the swing disappears and keep the screws on with tight lines and lengths, but, most importantly, wipe out batting line-ups with the reverse swing when the ball gets old.

Reverse swing is an art, which can only be achieved — without any suspicious looks — when the squares are hard and dry.

But, Pakistan, who had put their all hopes of winning this Test on their faster men, laid out a lush green square, denying any wear and tear on the ball, which effectively rendered them ineffective after the Kookaburra lost its shine after the initial 10 to 12 overs.

It was quite a week for Pakistan. There have been many such weeks. But, this week underlined the extent to which Pakistan cricket could be ironic.

That teams nowadays tailor conditions in long-form cricket to suit their resources is an accepted norm. But, that Pakistan even failed on that front sheds light on the decline that game in this country is going through.

The past week started with the hope of a reset but ended in despair.

Pakistan cricket faces a serious crisis.

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.