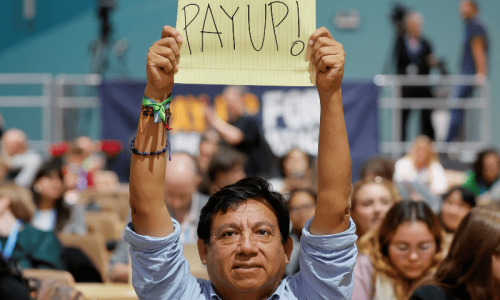

THE $300 billion package, agreed upon at COP29 in Baku as the new finance goal, is nothing to write home about and many from the developing world and civil society organisations fear it will jeopardise their efforts to adapt to the changing climate.

For context, Pakistan alone needs $380 billion by 2030 to meet its climate goals, and the delegation expressed its disappointment at the closing plenary.

“We are leaving Baku with mixed feelings and a heavy heart. We note critical gaps in the decision we all adopted here … Global solidarity is important but the goal put forward by the developed countries does not match with the needs of the developing countries,” Romina Khurshid Alam, the PM’s aide on climate change, said in her speech at the closing plenary.

The Global South had demanded $1.3 trillion annually, but after almost a week of delaying tactics, the first draft agreement only mentioned ‘X’ trillion instead of an actual number.

Goal doesn’t match needs of developing world, Romina tells final COP29 plenary

Subsequently, $250 billion was offered, which was termed ‘insultingly low’ by the developing bloc. Eventually, $300 billion a year by 2035 was offered in the revised draft agreement, which was shared after midnight, and despite reservations on its quantum and quality, it was adopted by the plenary.

According to AFP, the applause had barely subsided when many developing states delivered a full-throated rejection of the deal, with the Indian delegate terming it a “paltry sum” and “an optical illusion”.

Sierra Leone’s climate minister Jiwoh Abdulai said it showed a “lack of goodwill” from rich countries, while Nigeria’s envoy Nkiruka Maduekwe put it even more bluntly, saying, “This is an insult”.

The agreement for the new collective quantified goal (NCQG) highlighted that “costed needs reported in nationally determined contributions of developing country parties are estimated at $5.1–6.8 trillion for up until 2030 or $455–584 billion per year and adaptation finance needs are estimated at $215–387 billion annually for up until 2030”.

According to the document, the gap between climate finance flows and needs, particularly for adaptation in developing countries, was concerning, and all parties were asked to work together to enable the scaling up of financing to developing countries.

One of the main points of disagreement was the quality of finance, as the Global South had been demanding public finance instead of mobilisation of private funding. The text, however, called on “all actors to work together to enable the scaling up of financing” to developing countries for climate action from all public and private sources to at least $1.3 trillion per year by 2035.

According to journalists present at the plenary, the agreement was gavelled through, with the presidency hardly giving the delegates any time to register their protests.

The new agreement decided to periodically take stock of the implementation of the NCQG decision as part of the global stocktake and to initiate deliberations on the way forward prior to 2035, including through a review of this decision in 2030.

Sanjay Vashist, director of the Climate Action Network South Asia, said the developing world needs at least $1.3 trillion for mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage, and by throwing $300 billion on the table and kicking any and all real decisions down the road to 2035, rich countries had not only betrayed the people of the Global South, but also their own citizens, who had hoped that their governments will finally grow a spine and act responsibly.

“Tonight in Baku, the masks have come off [and] rich and developed countries’ governments have revealed their true intentions, that they never intended to honour any of their commitments made under the Paris Agreement. Their addiction to fossil fuels has blinded them and they have allowed the over 1,000 fossil fuel industry representatives to hijack the COP29 negotiations,” he added in his statement.

SDPI Executive Director Abid Sulehri, who was part of Pakistan’s negotiating team, told Dawn that the $300bn agreement doesn’t match either; the urgency and ambition required to rescue the Paris Agreement, or the ambitious agenda that the developing countries are required to pursue to implement their NDCs.

“Although the number seems three times higher than what was agreed in Paris (i.e. $100bn every year till 2020), one must keep in mind that after adjusting for US inflation, the $300bn figure will be too little and too less. In the spirit of multilateralism we should cautiously welcome COP’s decision but should keep on pressing the developed countries to pay for their historic emissions.”

The only significant outcome, which made every government happy at this summit, was the carbon market guidelines adopted under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

This story was produced as part of the 2024 Climate Change Media Partnership, a journalism fellowship organised by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and the Stanley Center for Peace and Security

Published in Dawn, November 25th, 2024

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.