FROM Bhashani Sweets, it takes only a few minutes to reach Bangla Bazaar, and a quick stop at Dhaka Fabrics for a ‘ghamchha’ or ‘lungi’ is followed by another brief visit to Chittagong Chemicals for any pesticide you might need.

In just half an hour, you can experience the vibrant streets of Dhaka, Chittagong, Gazipur, Khulna, Rangpur, or Narayanganj — all in the heart of Karachi. These businesses, located in Orangi Town, though well-established in their own right, share a deep-rooted connection to the personal histories of their owners.

Each story is unique, but many are marked by the haunting memories of the 1971 war — or the ‘Fall of Dhaka’ in the official Pakistani narrative — and the longing to revisit their birthplace, which they still see as a lost homeland. Many of them still carry the scars of the secession.

In the port city, countless tales trace back to the fateful events of Dec 16, 1971, when Bangladesh came into being, forcing many to migrate from what was once East Pakistan.

This year, however, as the 53rd anniversary of Bangladesh’s independence approaches, a sense of cautious optimism has emerged, replacing some of the grief that has long defined this chapter of history. In August, the fall of Sheikh Hasina Wajid’s autocratic rule gave rise to a renewed sense of hope among many Pakistanis, especially those who still feel a deep, personal connection to Bangladesh and its journey.

The ouster of Sheikh Hasina and the receptive attitude of Yunus-led regime in Bangladesh provide Pakistan a golden opportunity to rekindle the relationship with Dhaka

Shamim Akhtar and his family have been settled in Sector 11 ½ of Orangi Town since the mid-70s. The story of how they managed to escape with their lives and reach Pakistan in 1971 is a separate, heart-wrenching tale. Now, the only thing that has made them forget all their past sorrows is that next month, for the first time since 1987, they are going to visit their ancestral city – Khulna, the second largest port city in Bangladesh.

“I was 17 when my family and I prepared for our second migration after 1947…” he said. “In 1987, I visited Khulna with my wife, two daughters, and a son. There are still a few relatives who managed to survive the 1971 tragedy, and they are now settled there. Things began to deteriorate when Hasina Wajid came into power. Over the past 15 years, whenever we planned to visit Khulna, our relatives there advised us against it. Their only reason was, ‘Aap logo kay liye yahan halaat achaay nahin (the situation is not good for you here).’ It was all because of Sheikh Hasina’s anti-Pakistan thoughts and policies.”

Turning of the tide

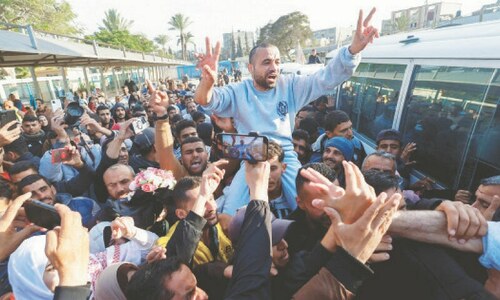

Now, after more than 35 years, Mr Akhtar, accompanied by his son, is set to fly to Bangladesh for a long-awaited family reunion. It’s not just the people of Pakistan who feel this way; these sentiments are equally shared in Bangladesh.

Maruf Hasan, a young Dhaka-based journalist who has extensively covered the recent political unrest and violence that led to the fall of Sheikh Hasina’s regime, is witnessing it unfold firsthand. “I believe that pro-Pakistan sentiment among the people of Bangladesh has grown in recent times,” he said.

“While this sentiment has always existed among many, people were not able to express it openly before. Now, they feel more empowered to voice their feelings. Several factors contribute to this, including ethnic ties and growing influence of anti-India sentiments.”

The events following the fall of Sheikh Hasina’s regime continue to send the same signals. In September, PM Shehbaz Sharif met the chief advisor of the Bangladesh interim government, Muhammad Yunus, on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly and called for the opening of a “new page” in their relations to enhance cooperation in various sectors. PM Shehbaz also invited him to Pakistan, reinforcing the importance of regional cooperation and dialogue.

Last month, a cargo ship from Karachi anchored at the port of Chittagong, establishing the first-ever direct maritime connection between the two nations. Many view this as a significant step towards strengthening trade relations. Pakistani traders were further pleasantly surprised when they received orders for the export of tonnes of sugar, rice, and potatoes from Bangladesh. It’s the first time in decades that Pakistan is set to export 25,000 tonnes of sugar to the riverine country.

The gesture didn’t stop there. The Consul General of Bangladesh met Pakistani traders last week, offering assurances for streamlined visa processing and also extending a formal invitation to the Dhaka International Trade Fair (DITF), set to take place in Jan 2025.

“Things have changed 180 degrees [since the fall of Sheikh Hasina’s regime],” said Zubair Motiwala, a prominent industrialist and Chairman of the Trade Development Authority of Pakistan (TDAP), who recently had a one-on-one meeting with Bangladesh’s Deputy High Commissioner in Karachi, S. M. Mahbubul Alam.

“It was incredibly difficult for our traders and businessmen to even secure a visa for Bangladesh during Sheikh Hasina’s government… But with the changing landscape, we are now eager to capitalise on the emerging opportunities. The Dhaka Trade Fair could mark the beginning of this new chapter.”

Cautious optimism

Despite all the positive developments, experts believe the biggest question remains: Can Bangladesh under Yunus forge a friendly relationship with Pakistan, leaving behind decades of deep ties with India? More importantly, will India tolerate this shift, and if not, how far will it go to protect its influence and investments in Bangladesh?

Author Dr Moonis Ahmar says that much remains to be seen in this regard.

The key question is whether Bangladesh can move beyond the wounds of 1971, which India has continued to exploit for its interests, and whether Pakistan can somehow heal those scars.

“The caretaker regime of Muhammad Yunus is certainly interested in mending fences with Pakistan,” says the former dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Karachi.

“But that basically depends on many domestic factors. We know very well that the Awami League, although it’s marginalised, has a deep-rooted presence in the institutions of Bangladesh like the judiciary, bureaucracy, civil society, academia, and even the military. So it’s true Yunus wants to come forward, but his hands are tied.”

He refers to “historical complexities”, particularly in the context of the 1971 war. For instance, Dec 16 is celebrated as the day of liberation in Bangladesh, while Pakistan considers it the ‘fall of Dhaka’. Dr Ahmar wondered how far the Pakistani government was receptive to the demand of Dhaka for an “unconditional apology”.

“Even when Gen Musharraf in 2002 had visited the National Martyrs Memorial outside Dhaka, it was a gesture very close to an apology when he had used the words that ’we regret,” he recalled.

“But again, domestic dynamics are very strong… The emerging situation in Bangladesh is definitely something which is a source of concern for the Modi regime. It has not been able to reconcile with the fact that they have lost Bangladesh, at least for the time being.”

Published in Dawn, December 16th, 2024

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.