MODERN automated traffic enforcement systems, even AI-powered ones, operate on a concrete set of rules: red means stop, green means go. In reality, even in the most organised nations, officers often disagree on whether a specific act constitutes a violation. A clip of a driver ‘rolling through’ a stop sign shown to two different police officers yields conflicting judgements. One officer might insist it’s a clear violation, while the other one, citing lack of evidence, might issue a warning at most. These discrepancies highlight a fundamental fallacy in automated traffic enforcement frameworks: although several traffic rules have been strictly defined, they still become fuzzy without relevant social context.

Unless explicitly encoded, contextual nuance is hard for AI to grasp. In the West, these gaps may come down to minor subjective judgements: no pedestrians, a deserted road, or an otherwise cautious driver. But in cities like Lahore and Delhi, these complexities get amplified several-fold. Beyond the jam-packed nature of the traffic — with rickshaws and bikes weaving through tight spaces within the lanes — the challenge also lies in comprehending the underlying social contracts and power dynamics at play.

Consider a scenario where an ‘influential’ person’s SUV, with blaring horns and tinted windows, shadows a vulnerable motorcyclist at a red light. Succumbing to the pressure, the biker prematurely crosses the red light to avoid confrontation. Should an automated system penalise the motorcyclist — or the SUV for intimidating them? Seeing this imbalance, an officer may exhibit leniency. Here’s another example, imagine a car almost dangerously speeding through traffic because the driver is rushing to get a patient to the hospital. Can an automated system truly understand the life-or-death context of the vehicle? On the contrary, an observant officer might even help the driver go quicker.

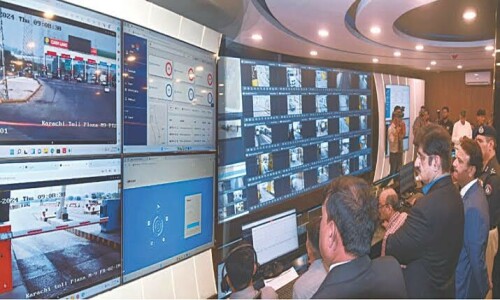

Automated enforcement will become as pervasive as traffic lights themselves.

These several would-you-rather scenarios bring a deeper truth to life: social context dictates the movements of traffic as much as, if not more, than traffic signals do. It can also be argued that in South Asian cities, the emphasis on social context for traffic moderation is far more than other mediums. People have internalised this unspoken ‘algorithm’ that guides their behaviour in day-to-day situations. A driver waving his hand to let the pedestrian cross the road even though it may be considered jaywalking, or a motorcyclist waving his hand rather than using the indicator to show their intention to turn. These subtle cues become second nature over time — forming a system of micro-negotiations that allow our traffic to keep flowing, even without strict adherence to the technicalities of the law.

Admittedly, these social cues also perpetuate unfairness in many regards. SUVs tend to be treated differently from cars, bikers and rickshaws. One may be forced to yield to others in several scenarios. If automated enforcement systems ignore these power imbalances, who is to say that such a system will not penalise the wrong party or inadvertently widen the inequities prevalent in our society?

Now the challenge tends to be twofold: first, current technology companies must acknowledge that binary rules are insufficient for any society; second, building better systems will require embedding social context to tackle the imbalances. Engineers and product managers cannot solve this alone. Anthropologists, sociologists, and behavioural scientists will

lead the next generation of development in this space. Identifying driving cues, power dynamics, and cultural norms that shape real-world interactions would enable us to distinguish between a reckless speeder and someone responding to an emergency — or recog-nise when a mot-orcyclist is acting out of caution rather than lawlessness.

Automated enforcement is here to stay, and these systems will become as pervasive as traffic lights themselves. Paired with AI — something that has already become an irreversible part of our infrastructure — these systems will monitor intersections throughout our cities to make communities safer. Minimising friction would require careful integration of many unwritten social rules: from how drivers coordinate on the road, to how officers assess violations. Ultimately, it’s not a debate of technical accuracy but rather one of nuanced social context understanding — one that respects micro-negotiations, hierarchies, and cultural norms that truly determine who goes and who stops. With AI, we have a chance to build a system that can accommodate such flexibilities and genuinely emulate how people navigate the roads every day.

The writer is a founding engineer of Obvio AI.

X: *@saqibama*

Published in Dawn, January 10th, 2025

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.