The moment one steps into the gallery, the sight is arresting: three humble matkas [clay pots traditionally used for storing drinking water], suspended mid-air, command immediate attention. Elevated from their earthly origins, they hover like timeless relics, defying gravity and transforming the ordinary into the extraordinary.

This striking display sets the tone for the exhibition ‘Clay – Earth. Malleable. Memory’ at Koel Gallery, Karachi, drawing the viewer into a world where clay becomes a medium of wonder, history and innovation.

According to Nurayah Sheikh Nabi, the curator of this masterful exploration of our enduring relationship with clay, “Clay is more than a medium; it is a keeper of stories, a bridge between past and present.” She further explains, “Artisans and visual practitioners innovate with age-old techniques passed down through generations to shape toys, ornaments, vessels, tiles, and sculptural forms.” This exhibition celebrates our enduring connection to earth — malleable and rich with memory — through contemporary practices that honour and expand upon ancient traditions.

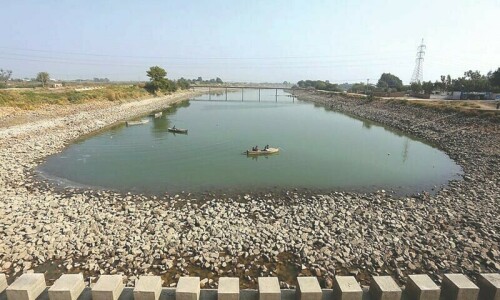

The journey begins with Harappa, an archaeological marvel on the banks of the River Ravi in Punjab, dating back to the Indus Valley Civilisation (3500–1700 BCE). Known for their advanced town planning, metallurgy and artistry, the Harappans left behind a legacy of pottery, jewellery and terracotta creations. Among their discoveries are animal figurines — bulls, rhinoceroses, elephants, crocodiles, birds and more — crafted in terracotta.

Age-old techniques are fused with modern sensibilities to striking effect at an exhibition that pays tribute to the everlasting allure of clay creations

The exhibition includes replicas of these ancient toys, popularised by archaeologist Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, who has excavated Harappa since 1986. Their presence here, crafted by the Chagatta Kumbhars of District Sahiwal, serves as a poignant reminder of our shared heritage, seamlessly linking the past with the present.

The Kumbhars, whose name originates from the Sanskrit word kumbhakar [earthen-pot maker], are found in nearly every district across the country. In Nasarpur — a historic town in Sindh located about 45 kilometres from Hyderabad and believed to be one of the oldest settlements of the Indus Valley Civilization — the art of glazing and hand-painting ceramics has become a hallmark of its cultural identity. This intricate craft, known as kashigari, involves creating stunning mosaic work by carefully cutting small pieces of coloured tiles and meticulously attaching them, piece by piece, to a surface.

The exhibition celebrates the rich terracotta pottery tradition with a display of exquisite kashigari pieces, alongside a video presentation and a live demonstration on the inaugural day. Featured artisans include potters from Moach Goth (located off Hub Chowki Road, Karachi), the Kashigar Karkhana of Nasarpur, the Gull Kashi Centre of Hala, and practitioners from the renowned Kashigari hub in Nasarpur.

The Daudpota brothers, Ghulam Hyder and Amjad, both trained at the National College of Arts (NCA) in Lahore and at the King’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts in London, have worked to preserve and modernise Nasarpur’s Kashigari tradition. Their ceramic tile-making processes were influenced by the Iznik style of making and glazing in Turkey. In this ‘under-glaze’ technique, clay is shaped in moulds or on potters’ wheels, undercoated and kiln-dried and then decorated. When the paint dries, it is glazed and fired again.

This exhibition is brimming with standout pieces, but one pairing truly captures the imagination: the legendary late ceramist Mian Salahuddin’s iconic hand-built and glazed stubby horses, displayed alongside Adeel Uz Zafar’s Toy Horse, an engraving on plastic vinyl rendered in his distinctive monochromatic style. Though born four decades apart and working in vastly different mediums, the juxtaposition of their works invites a compelling dialogue. Salahuddin’s earthy, tactile creations resonate with Zafar’s meticulous, modern precision, forging an unexpected yet profound connection between their practices.

Sadia Salim, a multidisciplinary artist and former head of the Department of Ceramics at the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, is noted for her work in ceramics. Her series Memory of a Landscape, stored in a glass box and captured in striking black-and-white images by Humayun Memon, features delicate porcelain forms inspired by plant life. The fragile ceramic pods and disintegrating pine cones poignantly highlight the vulnerability of our ecosystem, with the cones symbolising nature’s delicate balance as they shelter the seeds of conifer trees.

Nabahat Lotia, author of the meticulously researched Pottery Traditions of Pakistan, presented a gas-fired wall relief titled Kundan. Crafted in red clay, the piece features three squashed, urn-like forms — one turned upside down — symbolising the kiln’s unpredictable nature. It captures the delicate tension between the potter’s meticulous craftsmanship and the uncontrollable forces of fire that ultimately shape the final creation.

Anila Ashraf’s Moon Jar series masterfully blends tradition with innovation. Inspired by the ceramics of Korea’s Joseon dynasty, the self-taught artist transforms wheel-thrown forms with distinctive glazes. The textured peeling of the outer layers and the leather-like coating, partially revealing one jar’s smooth interior, creates a captivating interplay of surfaces that is both tactile and visually striking.

Aamna Talpur, a recent graduate in ceramics from Shaheed Allah Buksh University in Jamshoro, draws inspiration from the vibrant and deeply rooted textile tradition of Sindh — the ralli. Known for its bold geometric patterns, vivid colours, and intricate stitching, the ralli quilt is a functional and artistic creation crafted by women in rural communities. These quilts are pieced together using scraps of fabric, often recycled from old garments, and stitched with meticulous handwork. Talpur’s Rallis, Folded piece has been beautifully executed in glazed stoneware clay.

Aisha Tahir, who studied at the same university, showcased the transformative powers of her works in Carton Box and Newspaper, made in stoneware ceramics. In his three mask-like human faces titled Layers of Being, Fraz Mateen explores the many layers that form our identities. Salman Ikram’s several exquisite stoneware vases were a pleasure to behold.

Javaria Ahmad, who teaches at the NCA in Lahore, presented her Amma Ke Khat series, mostly consisting of envelopes in stoneware and porcelain. Abeer Asim’s Layers of Memory evokes a sense of remembrance. Shazia Mirza, with an impressive list of residencies from Provence in France to Thailand to Iceland, showcased small pieces of jewellery in porcelain. Shazia Zuberi, who began as a clay artist in the late nineties, displayed The Clay Artist’s Studio, an intriguing display showcasing various tools, different types of clays such as volcanic, kaolin, ball, fire and Thar clay, as well as quartz and glazes.

In a world of constant change, this exhibition stands as a tribute to the malleability of both earth and memory — an ever-evolving testament to the creativity, resilience and heritage of the human spirit.

‘Clay – Earth. Malleable. Memory’ was on display at Koel Gallery in Karachi from December 17, 2024-January 7, 2025

Rumana Husain is a writer, artist and educator.

She is the author of two coffee-table books on Karachi, and has authored and illustrated 75 children’s books

Published in Dawn, EOS, January 12th, 2025