From darkness to light: The promise of decentralised community-driven energy in northern Pakistan

For nearly 12 million people in Pakistan, access to electricity remains a distant dream. The country faces severe challenges — its national grid struggles to reach remote regions, energy prices soar, and energy security remains fragile.

In northern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), over half the population lives below the poverty line, and in the newly merged districts, this figure jumps to 72 per cent. For these communities, access to energy isn’t just a convenience, it’s a lifeline. High electricity prices push families into energy poverty, forcing them to rely on costly, unreliable alternatives.

Yet, there is hope.

Decentralised, community-driven solutions, particularly hydropower, could offer a way out. KP alone has the potential to produce up to 64,000 MW of electricity through small hydro projects — enough to power millions of homes sustainably.

Over the past decade, the provincial government has embarked on an ambitious journey to electrify its remote regions by building over a thousand micro-hydropower (MHP) units. These projects, supported by well-regarded local organisations such as the Sarhad Rural Support Programme (SRSP), the Aga Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP), and Haashar Association, take a community-based approach, aiming to empower local residents through energy. The initiative promises to transform lives, and hundreds of MHPs have succeeded in bringing electricity to the region.

But as with any ambitious plan, challenges abound. Field reports indicate that over 150 units installed since the early 2000s are now non-operational. What can we learn from these successes and setbacks? To find out, we conducted a detailed assessment of MHP infrastructure, combining field visits, key stakeholder interviews and in-depth case studies of three projects in Chitral and Swat. Here, we share the key insights and lessons learned.

Building resilience — where people and technology meet

When it comes to small hydropower projects, success doesn’t just depend on the technology. It’s as much about the people and communities using the technology. In energy projects, this blend of the social and technical — the “sociotechnical” approach — shapes how well these projects deliver real benefits. And in northern Pakistan’s remote areas, this approach has made a tangible difference.

Community-based MHP projects in KP have catalysed substantial socio-economic improvements in impoverished communities, which can be seen in enhanced educational opportunities, poverty reduction, economic development, and women’s enhanced entrepreneurship and health.

Take Kalam, for example. Thanks to two SRSP-managed power plants, there has been a noticeable boost in girls’ school enrolment. The reliable electricity has also powered up healthcare, small businesses, and agriculture, creating new income opportunities and reducing food insecurity. At the same time, the Jungle Inn MHP has been a game changer for local hotels and businesses, allowing them to stay open longer, attract more tourists, and slash their energy bills.

On a household level, these MHPs have helped families switch from costly wood and biomass to cleaner, cheaper electricity. The shift has led to better health outcomes, with fewer respiratory problems and lower medical expenses. According to SRSP, since 2016, these projects have cut carbon emissions by 66,000 tonnes annually and reduced community reliance on fossil fuels.

But it’s not all smooth sailing — MHPs face tough challenges, especially with the unpredictable weather patterns in northern Pakistan. Variability of water flow, increasing droughts and flash flooding cause technical problems while extreme vulnerability to climate change is making things worse. Transporting machinery to remote areas is also a logistical nightmare due to rough terrain and poor road access, impacting project cost and complexity.

The projects that thrive are those with strong community involvement and good governance. Unfortunately, many struggling MHPs are held back by poor maintenance, limited technical expertise, community conflicts and local disputes. Our research also uncovered a serious lack of record-keeping in terms of monitoring and evaluation. Many projects have no hydrological data or performance records, and there’s no public information on why some MHPs have failed. This lack of transparency and oversight limits the growth of small-scale renewables, despite their potential to significantly enhance the country’s energy landscape.

Decentralisation and the dream of energy democracy

Decentralising energy projects sounds like an ideal solution — more control for local communities and energy systems designed to fit their needs. But it’s no silver bullet. In northern Pakistan, where energy infrastructure is slowly expanding to reach underserved areas, decentralisation has exposed serious challenges in governance.

MHP projects are intended to be collaborative efforts, built on participatory decision-making. They bring together a wide range of players: government departments such as the Pakhtunkhwa Energy Development Organisation (Pedo), non-profit organisations (NGOs), Rural Support Programmes (RSPs), local authorities, donors, community organisations, and engineering consultants. Ideally, these stakeholders would work in harmony to plan, fund, and operate the plants under a shared “build-operate-transfer” framework. But that’s not always how it plays out.

The reality is often messy. Governance can break down due to vague roles, imbalanced responsibilities, and a lack of formal ownership agreements. These gaps lead to mismanagement and inefficiency. Communities have reported that funds generated from electricity sales were poorly managed and that promised job opportunities never materialised. Internal issues like nepotism and local power struggles further undermine the fairness of decision-making, reinforcing existing inequalities. Adding to the strain, local governments often lack the capacity to manage these technical projects effectively.

The broader context doesn’t help either. Sectarian violence and political conflicts in the region create instability that can derail projects. Even with recent governance reforms in KP, the region still relies heavily on foreign aid. Donor-led initiatives, with their rigid priorities and short-term funding cycles, can hinder local capacity-building and long-term resilience. That said, there are signs of progress.

Social enterprise models are emerging as a promising alternative, though much more needs to be done. Strengthening local governance frameworks, diversifying funding sources (through options like public-private partnerships, green bonds, and carbon financing), and increasing community involvement are crucial steps forward.

Despite these hurdles, the success stories show that when governance aligns with community needs and participatory processes, decentralised projects can thrive. The dream of energy democracy — where communities control and benefit from their own energy resources — remains within reach, provided we address these governance challenges head-on.

Women in power — driving change in energy projects

When MHP plants light up a community, the benefits often ripple out to women in profound ways. Electricity access has improved education and healthcare for women and girls, boosted literacy rates, and eased daily tasks. Programmes like Pedo’s Ujaloon Ka Safar and RSP-led initiatives have supported women’s socio-economic development, helping them gain better opportunities.

But the picture isn’t all bright. While electricity has made some household chores easier, outdated cooking practices still persist. Women remain reliant on inefficient, polluting fossil fuels such as firewood for cooking — a task that is both time-consuming and harmful to their health. During our surveys, many residents expressed a desire to switch to modern electric appliances, such as washing machines and cookers, but only if costs could be kept manageable. Clearly, any future improvements to MHPs must prioritise access to clean, affordable cooking solutions to truly benefit women.

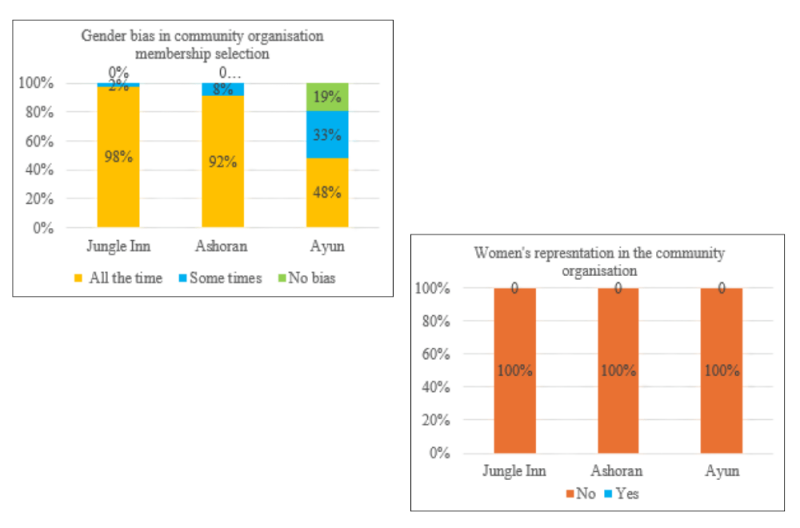

Despite progress made, gender development remains slow and at times regressive. In a region where gender roles are conservatively defined, women are rarely involved in the planning or management of energy projects. Gender bias still influences who gets a seat at the table in community energy organisations, leaving women with limited say in decision-making. While hundreds of women’s organisations have been set up under RSPs, their scope and effectiveness vary widely across different cultural contexts.

Development programmes have spent decades trying to promote gender equity, but the results have been modest at best. In KP, projects have addressed women’s immediate needs, but they’ve done little to support their broader aspirations — like becoming leaders or entrepreneurs. While a handful of women have launched small businesses thanks to electricity access, many remain confined to traditional roles within the home. Political instability, religious extremism, and entrenched patriarchy continue to block women’s participation in public life and local governance.

That’s not to say these programmes have failed. Initiatives led by organisations like SRSP have made a real difference, improving education and skills for many women. Yet after 30 to 40 years of development work, progress is painfully slow. Female literacy in KP stands at just 37pc, compared to 72pc for men, and nearly 40pc of girls are still out of school. A recent UNDP report reveals that gender inequality is actually worsening, with women’s labour force participation dropping from 16pc in 2006-2007 to just 11.3pc by 2018-2019. Parliamentary representation for women has also declined slightly over the same period.

Why do these disparities persist?

One major reason is that development projects often focus on short-term outputs — such as building schools or distributing resources — without tackling the root causes of gender injustice. Unequal access to resources, power imbalances, and rigid social norms remain largely unchallenged.

The lesson is clear: to build resilient energy systems, we must actively empower women. Studies show that when women play a leadership role, resource management improves, and projects become more adaptable to change. For MHPs and similar initiatives to be truly transformative, they need to support women’s agency, not just their participation. That means involving women at every stage of the project, from planning and execution to governance. Only then can energy access become a tool for empowerment and equality.

Towards resilient and inclusive energy futures

As KP continues to navigate the challenges and opportunities that come with decentralised energy systems, the experiences with MHP projects offer crucial lessons on how localised energy solutions can be refined to better serve communities. These projects are vital for achieving sustainable development in remote areas, but success isn’t just about installing turbines or building infrastructure. It’s about creating systems that are both resilient and equitable — where technology and community needs are deeply interconnected.

From a technical standpoint, we observed that small MHPs (under 100kW) face greater operational challenges than larger ones, highlighting the need for more careful feasibility assessments. However, technology alone won’t ensure sustainability.

Strengthening local institutions, project monitoring, and inclusive governance are critical. Communities must have a genuine role in decision-making, and projects need to address underlying power dynamics and inequalities. As climate change intensifies, adaptable and resilient energy systems will be crucial for northern Pakistan’s survival and growth.

The future of rural electrification in KP and similar regions globally depends on understanding the socio-technical nature of these projects — where technology meets human lives, and where power should mean not just electricity, but empowerment.

Disclaimer: This study has been published as an open-access peer-reviewed journal article in Environmental Research: Infrastructure and Sustainability and can be accessed here. We are grateful to the British Council Researcher Links Climate Challenge Workshops Grant: Delivering a Sustainable Energy Transition for Pakistan for funding this project. We also acknowledge the support of Pedo, SRSP and the Energy & Power Department KP in facilitating data collection and field visits.

Header image: The tourist’s hub, Kalam Valley in Swat, powered by local MHP plants. — photo by author