The dispute between US President Donald Trump and Ukrainian President Vlodymyr Zelensky in the White House did not occur by chance. On the contrary, it was a calculated move designed to signal to everyone — especially Republican Party elites — the kind of foreign policy Trump intended to pursue the following four years.

ISOLATIONISM OR GLOBALISM

The tension between isolationist and globalist tendencies in US foreign policy has existed for over a century. One of the most significant expressions of globalist aspirations came in 1918, when President Woodrow Wilson outlined his Fourteen Points, advocating for a new world order after World War I. Wilson proposed the establishment of the League of Nations. However, when the League was formed, the US senate refused to join, demonstrating America’s strong isolationist reflex.

Americans have their reasons for supporting isolationism. The US is geographically shielded by two oceans and shares borders only with Canada and Mexico, providing it with security. Moreover, its location keeps it distant from Europe and Asia, reinforcing the inclination to avoid entanglement in foreign conflicts.

Another reason for an inward-looking isolationism is the vast size and internal diversity of the US. Living in a federation comprising 50 states and a landmass nearly 40 times the size of the UK, Americans often find their own country sufficient for engagement and exploration, reducing the necessity of travelling to the rest of the world.

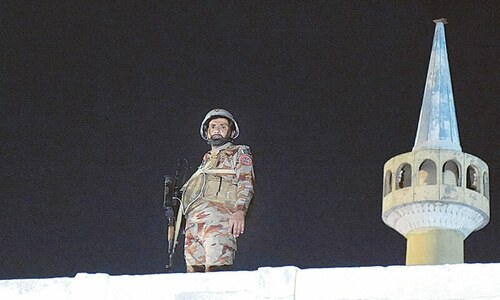

From Ukraine to Gaza, US President Donald Trump’s foreign policy favours strength over stability. But with a divided nation and strained alliances, will his approach hold?

Despite all these conditions, the US adopted a globalist foreign policy after World War II. The US defeated Japan and Germany and then pursued a global containment policy against the Soviet Union.

During this period, the US accounted for nearly 40 percent of global economic production. American companies’ need for new international markets and Americans’ increasing dependence on oil imports made globalist policies an economic imperative.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Cold War ended. Yet, a decade later, the September 11, 2001 attacks ushered in a new global priority: the ‘War on Terror’. The George W. Bush administration invaded Iraq and Afghanistan. Although Barack Obama viewed these invasions as strategic mistakes, his administration largely maintained globalist policies.

Trump, in contrast, put forward the slogan “America First” in his first term, signalling a shift toward isolationism. However, his presidency saw few substantive changes in foreign policy. After Trump, the Joe Biden administration reasserted the Western alliance under US leadership, in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Immediately after his re-election, President Trump moved to cut off support for Ukraine, using pro-Russian rhetoric to sever the US from the Western bloc and abandon its perceived role in maintaining the world order.

CHAOS AT HOME, CHAOS IN THE WORLD

Trump’s stance on two major war zones reflects a consistent pattern: siding with the strong against the weak. In Gaza, he openly suggests expelling Palestinians — an idea even Israel refrains from stating outright. In Ukraine, he falsely claims that Zelensky is an unpopular dictator who initiated the war — an accusation so extreme that even Russia does not make it.

Trump’s suggestion about Gaza contradicts international law and numerous UN decisions. His actions towards Ukraine disregard the international treaties the US and Russia signed to guarantee Ukraine’s territorial integrity in exchange for surrendering its nuclear weapons. Yet, for Trump, such commitments are not important. His sole guiding principle is power.

Trump has the power to do whatever he wants in the short term. Republicans in Congress and the conservative-majority Supreme Court are unlikely to challenge a newly elected Republican president. But will he succeed in the long run? Three major factors undermine his prospects.

First, Trump won office with the support of only half the electorate, and his approval ratings have already fallen below 50 percent. His two main economic policies — raising tariffs and deporting a large number of immigrants — will drive up prices and inflation. Yet, he campaigned on lowering costs. Unlike some other societies, Americans have little tolerance for economic stagnation.

Second, Trump has no friends in international politics other than Russia and Israel. In just a month, he has managed to strain ties with America’s closest neighbour, Canada, and key European partners. The isolation in foreign policy will have an economic cost for American companies. It is impossible to keep enjoying the economic benefits of the global order while also trying to destroy this order. Tesla’s declining sales in Europe and tumbling stock prices for the past month signal that the economic fallout has already begun.

Third, Trump is taking these geopolitical risks at a moment of domestic turmoil. His decision to appoint Elon Musk to lead a new cost-cutting agency has led to mass layoffs of federal employees, with Musk publicly ridiculing bureaucrats as a class. This fuels the perception that the administration embraces confrontation — both at home and abroad.

Trump’s ultimate success remains uncertain. But one thing is clear: The global order that the US once led has been dismantled — by none other than the US president himself.

An Indonesian version of this article has been published in Indonesian daily Kompas and an Arabic version has been published on the Al Jazeera website

The writer is Professor of Political Science at Saint Diego State University in USA and the author of Islam, Authoritarianism and Underdevelopment, which has recently been translated into Urdu.

X: @prof_ahmetkuru

Published in Dawn, EOS, March 23rd, 2025