In Pakistan and among the Pakistani diaspora, it is heartening to see the strong emergence of a new generation of gifted English language poets and prose writers, in both fiction and non-fiction.

Another striking difference they clearly bring forth from their predecessors (barring a few) is their facility in using the English language on their own terms. They are neither imagining their creative exercise as an attempt to master the master’s language to prove to the master that they are equally good, nor do they remain captive to a colonial linguistic sensibility. They see the language as incidental to their art, a tool of their own that is not borrowed from someone else.

Since the arrival of 2025, two major anthologies of Pakistani Anglophone writing have appeared. In the New Century: An Anthology of Pakistani Literature in English, compiled and edited by Muneeza Shamsie and published by Oxford University Press (OUP), is a monumental work that includes writings from and commentaries on 88 poets and prose writers from the time of the creation of Pakistan to the present day.

This work can be seen in harmonious continuity with Shamsie’s earlier books, The Dragonfly in the Sun (OUP, 1997) and Hybrid Tapestries (OUP, 2017). After some initial work on chronicling, compiling and critiquing Pakistani Anglophone writing by Dr Tariq Rehman, it is Shamsie who has consistently and diligently researched and documented the history of Pakistani English literature.

The other anthology of significance is Poetry in English from Pakistan: A 21st Century Anthology, edited by Ilona Yusuf and Shafiq Naz and published by Alhamra Publishing. There is a careful selection of works from poets belonging to different generations and coming from varied backgrounds. Reading this selection feels like holding a bright, colourful bouquet with flowers delicately picked and arranged by Yusuf and Naz.

Together, the compilations by Shamsie and Yusuf and Naz establish that creative writing in English is no more on the margins but has become a part of the mainstream Pakistani literary discourse.

When it comes to determining the place of Pakistani English literature within the larger multilingual canon and literary landscape of Pakistan, people tend to take two extreme positions. For some from the monolingual English speaking elite, any ‘vernacular’ has little worth. Therefore, they award our English writing the sole representative status, as it were. On the other hand, for many readers and writers of Urdu, Balochi, Sindhi, Punjabi, Pashto or other languages in which we create literature, English remains an alien language in which nothing worthwhile can be produced by Pakistanis.

Both these positions are based either on ignorance or preconceived notions of superiority of one over the other. If we have produced Ghani Khan and Shaikh Ayaz in Pashto and Sindhi, we have also produced Bapsi Sidhwa and Taufiq Rafat in English. However, it must be acknowledged that in Urdu and a host of other languages that Pakistanis speak, we have produced a far bigger and representative body of work than in English.

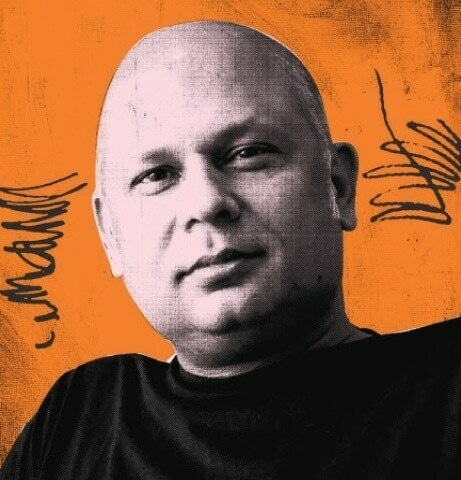

Any serious anthology is quite comprehensive but, while an anthology can be representative, it cannot be exhaustive. Perhaps, being published in some reputed journal or preferably having a book or books behind you remains a consideration for the editors for your inclusion in their compilation. Although Makhdoom Ammar Aziz has published internationally in recent years, his first collection of poems, The Missing Prayers, has come out after the appearance of the two major anthologies I have mentioned above. I am sure his work’s definite merit will get it included in future representative compilations of Pakistani as well as international English poetry.

Aziz’s debut collection, almost simultaneously published in India by Red River, New Delhi, and Aks Publications, Lahore, brings together a moving preface by the poet and 53 poems organised in 10 sections over 136 pages. I first met Aziz 15 years ago and knew him as a young, promising filmmaker, a poetry and classical music buff and a voracious reader of books on politics, history, art and literature. The Missing Prayers doesn’t come as a surprise to me because I have seen him grow into a fine poet over the years. However, there is an element of wonder for me here because the way the collection is compiled also reads like a deeply personal memoir in verse.

The range of thoughts and themes depict the chief concerns of Aziz — family, migration, personal history, politics, socialism, peace in South Asia, the raags and ragnis of Indian classical music, love, relationships, universal human suffering and an intensely felt angst of a creative soul. Although the book is dedicated to his mother, Aziz affectionately remembers his maternal grandfather who lost all his literary work during the partition of Punjab. In some sense, Aziz sees his first book compensating for the loss of his grandfather’s writings.

The paucity of space only allows me to introduce the readers to a couple of examples from Aziz’s verse. In one of his most powerful and longish poems in multiple parts, ‘The Brown Man’s Ballad of The Virgin’, Aziz writes: “…The virgin, I swear,/ is not what you imagine/ despite these antiquated/ lyrics that mimic/ our colonial masters/ who never expected/ us to write in their idiom,/ never understood/ our metaphors/ of the world as a wine-tavern,/ or night as the curls/ of a woman’s hair –/ they silenced our ballads/ with a piercing hiss…”

In his poem ‘My Marxist Uncle Tells Me About Karbala’, Aziz says: “… The world laughs at him/ but my uncle silently cries —/ how he cried/ when the name of Leningrad/ was changed to ‘something strange.’/ ‘But Karbala,’ he whispers/ ‘will never change’.”

The section of the book called ‘Raagmala’ is particularly moving. The poem titled ‘Purya Kalyan’ ends with the lines: “Mother is a minor raga/ melded with a major scale./ I chase her on keys/ and strings of love/ from one octave to another.”

The writer is a poet and essayist. His latest collections of verse are Hairaa’n Sar-i-Bazaar and No Fortunes to Tell

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, March 30th, 2025