The PPP government apparently panicked and yielded to the pressure of the brokers’ community by extending the capital gains tax exemption by not one but two years in an unusual move well before a week of the announcement of the federal budget. Besieged by the PML(N) and the lawyers, feeling the heat from the media, and faced with worsening economic indicators, the government decided to make peace with Karachi’s powerful brokers’ group.

The PPP government apparently panicked and yielded to the pressure of the brokers’ community by extending the capital gains tax exemption by not one but two years in an unusual move well before a week of the announcement of the federal budget. Besieged by the PML(N) and the lawyers, feeling the heat from the media, and faced with worsening economic indicators, the government decided to make peace with Karachi’s powerful brokers’ group.

It was the first test of its political will to undertake difficult reforms – a test it failed. That it could not wait even for a week to make this announcement along with the budget speech shows its increasingly vulnerable political position.

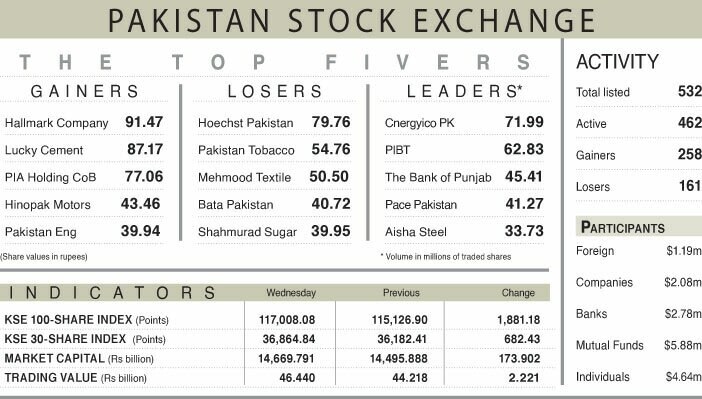

The stock market plunged by 19.78 per cent during May 2008 in its worst percentage loss for a single month since May 2000 when it dropped by 19.17 per cent; weeks before the Musharraf government was to present its first budget. The market had fallen by about 7.5 per cent for the month till May 21, 2008 but the monetary tightening measures announced on May 22 pushed it further into red by another 12 per cent in just seven trading sessions. It is hard to say how much of the fall was engineered or not but one fact is clear. May has been the worst month for the stock market during the last ten years as illustrated by the following graph:

Leaving aside the issue of if there was a deliberate manipulation to put pressure on the government to continue the exemption of capital gains from tax, let us examine the arguments in favour of this exemption. However, it is important to clear one widely held and absolutely wrong notion.

Pakistan is one of the few countries where the financial intermediaries like brokers and other financial institutions claim the trading income to fall under the definition of capital gains. Most countries tax the trading income of brokers and banks as ordinary business income at standard tax rates and not as capital gains, because trading forms part of their ordinary business.

Unfortunately, the policy makers and the public opinion in Pakistan have been mislead to believe otherwise by the vested interests and some inexperienced and naïve media persons who do not always do their homework. In India, trading income from stocks (where the delivery of the shares is not taken) is taxed as speculation under section 43(5) of the Income Tax Act at the standard rate of 30 per cent plus other surcharges. India has had a tax rate of 10 per cent on short-term capital gains (from disposition of securities where the holding period is 12 months or less) for many years for both locals and foreigners. Indian government increased this tax to 15 per cent in March 2008 budget.

India however continues to exempt long-term capital gains (where holding period is greater than 12 months) from tax. The policy objective has been to encourage longer term investment and minimise short-term volatility in the financial markets and this tax regime has served Indian market well. The income from trading of shares was tax-free in Vietnam till November 2007 when it imposed a 20 per cent tax to discourage excessive and volatile trading.

Another argument in favour of the tax exemption is that Pakistan needs foreign investment. This is true but the appropriate way to encourage this is to grant tax exemption to pre-qualified foreign institutional investors as India and Taiwan do. This prevents the abuse of the “foreign investors’ window. In any case, about 70 per cent of Karachi’s daily trading volume is attributed to the local investors who not only trade excessively but on very low (10-15 per cent) collateral. This highly leveraged and excessive trading contributes to higher volatility, is potentially destabilising for the system, and a drain on scarce credit resources of the country that is already under the burden of excessive government debt.

Karachi’s stock market is probably the most speculative in the world when measured in terms of the ratio of average daily trading volume (in value terms) to free-float market capitalisation. Free float denotes those shares that are available for trading and excludes stakes of the government and strategic investors or sponsors. This is the most appropriate way to measure the market size. Pakistan’s free-float size has ranged between $6 and $8 billion recently and gives a realistic picture compared to the $60 billion figure cited by the previous government. The following chart compares the average daily traded value (in the past six months) to the Morgan Stanley Capital International’s free-float index of Karachi’s stock exchange with those of some Asian countries and the New York stock exchange. Karachi’s ratio is six to 19 times higher compared to the ratios of these exchanges.

For example, Karachi stock exchange’s average daily trading volume has been a staggering $400 million compared to $486 million for Kuala Lumpur’s although Malaysia’s market is much bigger with a free float market capitalisation of $83 billion compared to Pakistan’s about $6 billion. Even if the free float is taken to be $10 billion, Karachi’s relative volume ratio would still be seven times that of Malaysia.

A leading broker and a former director of the Karachi Stock Exchange speaking on the condition of anonymity, confirmed estimates that about 50 per cent of the local daily trading volume is conducted by 3-4 big brokers. The Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP) is a weak and toothless regulator with little capacity to properly regulate the market in accordance with international standards. The result is a market which is an insiders’ dream. The monthly volatility of Karachi’s free float index has been as high as 88 per cent on an annualised basis compared to the 24 per cent average for the emerging markets. In simple terms, a big trader can make 1-5 per cent a day on traded volume.

A large part of the trading is conducted though borrowed funds or the so-called CFS (which stands for Continuous Funding System) market. The CFS borrowings have averaged about Rs51 billion (or $840 million) during the past 12 months. [The Mumbai stock market used to have a similar system which was banned by the regulators in July 2001. That did not inhibit its growth.] This level of borrowing (not to mention borrowings through other channels) when put together with a daily average daily trading volume of around $400 million indicates that the so-called investment activity of the local punters is actually a highly leveraged trading game that uses public money and yet claims full tax immunity. Given that a large part of this activity is conducted with borrowed funds, there is little merit in the argument that this would move off-shore if taxed, especially if the exemption continues to apply to the long-term investors including foreigners.

The tall, vociferous, and often exaggerated claims about the importance of the stock market in Pakistan obscure the fact its growth has come from the increase in the float of public sector or privatised companies and it has played a negligible role in mobilising capital for the private sector. During 2006 and 2007, the new capital raised at the Karachi Stock Exchange was just around $170 million or less than 0.1 per cent per annum of GDP. Because easy money is made in trading, there are no incentives for the brokers to develop other areas of business such as underwriting of shares, quality research, corporate finance, corporate bonds, etc.

It can be argued that speculators provide much needed liquidity to the market and help determine the fair values of the shares. It is also argued that active markets help the government to get fair prices when it sells its stakes in the public sector enterprises. There is no doubt that active investors or speculators provide liquidity and perform an important function but it is seriously questionable that the excessive level of leveraged trading, such as in Pakistan, is really necessary or healthy to achieve those objectives.

It is in fact counter-productive because this degree of speculative trading has a huge opportunity cost in terms of funds or credit resources that otherwise could be more productively utilised in producing goods and services. Further, excessive volatility adds to the risk premium of Pakistan’s market and ultimately to cost of raising equity in the market. Both are detrimental to the stated objective of resource mobilisation for real investment activities.

The stock market currently contributes about $75 million a year to the tax revenues through different taxes such as capital value tax (CVT). The market can contribute a lot more if the trading activities are properly taxed and administered in a manner that involves no harassment of its participants by the tax officials. This can be achieved by rationalising the existing system and introduction of measures, such as acceptance of certification of tax calculation by chartered accountants and use of technology, which would prevent the tax officials from abusing their powers.

The continued exemption of the trading income (and not capital gains as most Pakistanis have been erroneously led to believe) represents a serious and harmful distortion in the fiscal policy. It sends a wrong signal to those who want to invest in manufacturing, agriculture or some other industry. Why bother with the pain and effort involved in running a factory? Just borrow some money and play the market! There is nothing wrong with playing the market and making money but it should not be at the cost of the exchequer and public money.

The writer is the author of “The Gathering Storm. Pakistan: Political Economy of a Security State”, and a former global emerging markets investments head of Citigroup. yousufnazar@yahoo.com

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.