NOW that the media's glare has shifted elsewhere, it is time to analyse the results of the just-concluded Pakistan-US strategic dialogue. Undoubtedly, Pakistan went into the talks with its negotiating position strengthened by recent developments; both at home and in Washington.

For a start, it was the first time that such sensitive negotiations were spearheaded by an elected government; secondly, the Pakistan Army's impressive performance against militants has had a powerful impact in the West; and thirdly, there is now a strong national consensus in favour of confronting the militants.

These helped reduce fears that it was only a question of time before the Taliban would overrun the capital and seize the country's nuclear weapons. The most critical, however, has been the 'change' in Washington's strategy on Afghanistan, with the Obama administration acknowledging that with no real possibility of the Taliban being defeated, the recent surge was meant only to strengthen Washington's negotiating position.

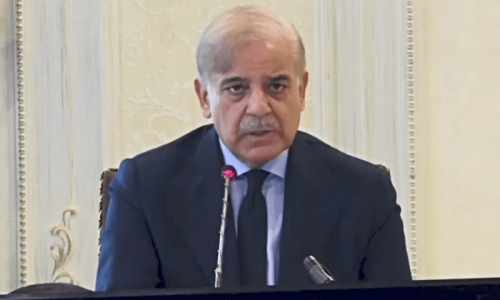

But even in the achievement of this reduced goal, Pakistan's role will be critical, which explains the refreshing change in Washington's tone and tenor. This not only encouraged our foreign minister to demand that it was time for the US to 'deliver', but for him to hand over a 56-page list of proposals.

The contents are not known, but it can be surmised that apart from weapons systems, Pakistan's interest was in obtaining tangible assistance to strengthen its economy, especially in the critical sectors of energy, power and trade. This was accompanied by a muted request for civilian nuclear reactors as well. On the political front, Pakistan expected greater US effort in influencing India to reduce its increasing presence in Afghanistan and acknowledgment of its role in the unfolding political developments in Afghanistan.

The joint statement revealed little that was comforting. While no proposal was rejected, Pakistan failed to make headway on any of the substantive issues. On trade, the US did give vague assurances to “work towards enhanced American access”, but this only indicated that a free-trade agreement is still far away. As regards our power needs, the US could come up with only $51m to upgrade three thermal power stations, while our request for civilian nuclear reactors was politely brushed aside.This means that while the US was willing to listen to Pakistan's concerns, it acceded too little of value, nor offered anything other than the promise of a sector-by-sector dialogue between the relevant ministries. On political issues as well, there was no mention of support for the resumption of formal Pakistan-India peace talks.

What then explains Foreign Minister Qureshi's ebullience, as evident from his claim of a “180-degree turn in US attitude towards Pakistan”? Admittedly, the meetings were marked by bonhomie and camaraderie, but this alone is not enough for a strategic relationship. More likely, we are entering into another episode in the history of 'transactional' relations, where GHQ and the Pentagon will provide the fulcrum for bilateral relations.

Nor was it lost on observers that the army chief was the real 'star' of the event. This, along with the primacy accorded to the security aspect, made it inevitable that some would fear that history was about to repeat itself. This is not surprising, given that the catalyst for the change in US attitude is its conviction that the Pakistan Army's commitment to maintaining pressure on the militants is essential for the US to have any success in its own military campaign in Afghanistan.

Notwithstanding our loud claims, the Washington dialogue was only the beginning of a 'process' which may have graduated from being 'transactional', but that still remains 'episodic'. Had it been otherwise, the Obama administration would have been more sensitive to our economic plight and given more thought to injecting a 'game-changer' in the relationship.

Two changes come immediately to mind agreeing to greater market access that could bring in another $10bn to Pakistan, thus freeing it from dependency on foreign assistance, and, two, with the country facing 12-hour loadshedding daily, not much effort would have been required to provide, on an emergency basis, half a dozen power plants, whose impact would have been dramatic.

Even the army chief pointed out that he would be willing to have the weapons systems delayed, if this could expedite economic assistance. Instead, Washington sought fit to warn us to stay away from the gas pipeline with Iran.

In the meanwhile, Obama's new Afghan strategy and the accompanying reaching out to Pakistan have prompted other regional players to scramble around to consolidate their positions. Delhi decided to resurrect its historic strategic ties with Moscow, while warning the US not to make the mistake of seeing different “shades within the Taliban”. The US responded by placating Delhi, announcing the completion of “arrangements and procedures” for US-origin spent fuel to be reprocessed in India.

Others too, particularly, Moscow, Beijing and Tehran, have engaged in a flurry of activity. In Kabul, Karzai has begun to show a degree of defiance that has impressed his supporters and dismayed the US. But his reaching out to Iran and China, just when the US and Pakistan were setting the parameters of their new relationship, has added a Byzantine twist to regional diplomacy.

The Americans are furious with Karzai, not only for his meeting with the Iranian president but also for his talks in Beijing, which revealed growing Chinese concern due to Washington's increasing military presence in Central Asia. Incidentally, a recent ChinaDaily editorial accused the US of pursuing “an offensive counter-terrorism strategy in Afghanistan, as a pawn to help it maintain its global dominance and contain its competitors”.

Of course, Pakistan is right to pursue the goal of strengthening and enhancing its relations with the US. After all, it is our major source of sophisticated weapons systems and also the biggest aid provider. But a 'strategic' relationship with the US, while it is determining the agenda and setting the parameters, could place severe constraints on our other important ties. We have to remain cognisant of these risks.

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.