Karachi – Pakistan’s biggest, most cosmopolitan and certainly its most complex city – is in trouble again.

To many Karachiites it’s the same old story: Some 25 years worth of bloody tales of ethnic rivalries, politicised crime, sectarian tensions and a bulging population that keep going under only to remerge over and over again to keep this maddening metropolis’ economics, politics and culture afloat.

Karachi is a stunningly diverse city. Many western scholars with an eye on Pakistan believe that if ever Karachi’s diverse ethnic, religious and sectarian groups manage to strike a workable socio-economic and political consensus, Karachi can become an 'Asian New York'.

But that hasn’t happened. Unfortunately Karachi’s ethnic diversity, especially after the mid-1980s, has remained to be a venerable entity in the hands of both military dictators and civilian politicians who have continued to exploit this diversity to encourage ethnic and sectarian cracks in Karachi’s varied polity to meet their own selfish, short-sighted and exploitative aims.

So much has been written about the perils of this city – once the thriving economic hub and entertainment capital of Pakistan. A city that still remains to be the country’s economic nerve centre, as well as perhaps Pakistan’s most liberal and secular conurbation. But it is also one of the most crime-infested cities in the region.

Mohajirs (Urdu-speakers) constitute 41 per cent of the city’s population followed by the Pushtun (about 17 per cent), Punjabi (about 11 per cent), Sindhi (about 6 per cent), Baloch (about 5 per cent), Sariki (about 3 per cent) and those from Hazra and Gilgit (2 per cent).

There are the ever-growing Afghan and Bengali migrant populations in this city plus Burmese, Nepalese and some Sri Lankan communities too. Karachi also has an enterprising and well integrated Chinese community mostly made up of the Chinese who migrated to Karachi during Mao’s Cultural Revolution in late 1960s.

Urdu is the most widely spoken language of the city, especially a layman and bazaar dialect of Urdu that also includes expressions from Pushtu, Punjabi and Sindhi languages.

The majority of Karachi’s population is Sunni Muslim (about 65 per cent) and it also has a significant Shia population (about 30 per cent). There are Hindu, a prosperous Zoroastrian, and vibrant Christian communities in the city as well (5 per cent). No wonder then, speeches made by the country’s founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, in which he most overtly advocated secularism were almost all made in Karachi.

The politics of the city mainly revolves around three political parties: The secular/Mohajir nationalist Muttahidda Qaumi Movement (MQM), the ‘left-liberal’ Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and the secular/Pushtun nationalist Awami National Party (ANP).

Other parties such as the fundamentalist Jamat-i-Islami (JI), the militant Sunni Thereek (ST), Jamiat Ulema Islam (JUI) and Pakistan Muslim League-N (PML-N) also have a presence in the city but are electorally weak.

Many see the violent eruption of ethnic riots of 1986 as the starting point from which Karachi never really managed to recover.

But was Karachi ever any different? It was. It was cheese to what has been chalk ever since 1986. In fact if one even briefly glances at what the city was like till about the late 1970s, they are bound to agree with those who claim that Karachi once had the potential of becoming Asia’s New York.

Before the lights went out

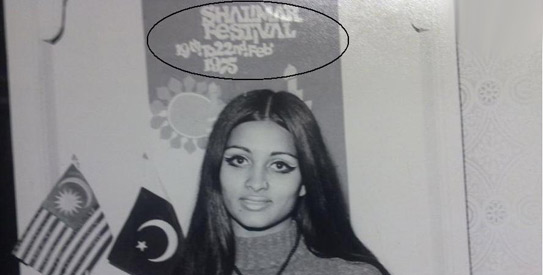

The 1970s witnessed the peak years of tourism in Pakistan. It would never again see the amount of tourists that thronged the streets of Karachi, Lahore and Swat from 1970 till about 1979.

Most of the tourists that arrived in Pakistan during the country’s tourism heydays were young western bohemians (Hippies). Pakistan was one of the many countries that lay on a celebrated path that was called the ‘Hippie Trail.’

The Hippie Trail was first taken by early hippies in the late-60s. These were young men and women who were rebelling against the “social constrains” of western societies.

To find “enlightenment” and “more organic cultures,” many young Europeans and Americans headed out towards India and Nepal on cheap cars, buses and trains, hitchhiking across East Europe, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan along the way.

Though the backpacking travelers lived and travelled cheap, the Hippie Trail spawned a thriving tourist industry in the areas that the Trail ran through.

Shaping in from Greece to Turkey to Iran and Afghanistan, the Hippie Trail then curved straight down into Pakistan through the Khyber Pass from where it ended either in India or Nepal.

Of course, like Iran and Afghanistan in those days, Pakistan too was a very different country than what it became many years later.

During the peak years of the Hippie Trail (1971-76) Pakistan was under the leadership of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

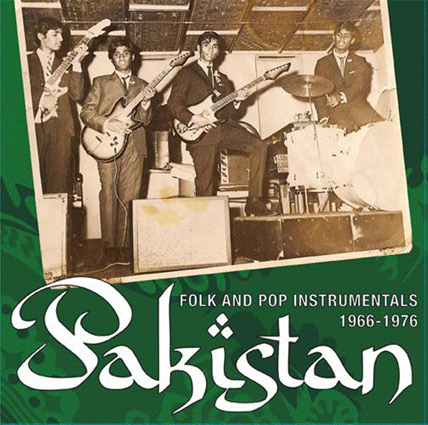

Karachi was the country’s economic hub and entertainment capital. Between the 1950s and late 1970s, Karachi had over five hundred cinemas; over three dozen night clubs, numerous bars, a well maintained race course and what are still perhaps some of the finest natural beaches in the region.

Hashish was easily available, but people still didn’t know what heroin or a Kalashnikov was. And though alcohol and gambling were legal, there was comparatively less crime.

“Men, women and children could walk the streets of the city till late at night and no one would bother them,” a 69-year-old Babu Ali told me. He used to run a small eatery in the Old Clifton area in Karachi in the early 1970s. “There was crime, but it was nothing compared to what we have today,” he added.

By the late 1960s tourism as an industry in Karachi was flourishing, so much so that in 1972 the government created the country’s first dedicated tourism ministry and department, with the main offices of the ministry situated in Karachi.

There was still no concept of the dreaded Pakistani fanatic in those days or the ethnic cleanser. From the Khyber Pass hippie travelers used to come down to Rawalpindi, took a train to Lahore and from Lahore entered India by another train. Many would venture down to Karachi as well, especially for its beaches.

Like other cities that were on the path of the Hippie Trail such as Athens, Istanbul, Tehran, Kabul, Delhi, Goa and Katmandu, in Pakistan Karachi too saw the springing up of hundreds of cheap hotels, restaurants and taxi and bus services. Thousands of Karachiites were employed here.

Most of these hotels were situated in the Saddar locality, while the famous Zainab Market, the Old Clifton area and the beaches at Hawkesbay and Sandspit were always packed with tourists, especially in the winter season.

A number of nightclubs did a roaring business too. The most famous were The Excelsior in Saddar, Oasis and Playboy on Club Road, The Horse Shoe on Shara-e-Faisal and Cave-Inn on Bandar Road. Alcohol was freely available in bars at these clubs while special liquor shops sold beer, whisky, vodka and rum, both local and foreign.

“Most beverages were made by local breweries (Murree and Lion brands),” says Haroon Raees who ran a liquor shop on main Clifton Road just opposite the Teen Talwar area in Karachi between 1969 and 1977.

His shop was destroyed by Jamat-i-Islami activists in 1977. “During the opposition parties’ protest campaign against Bhutto sahib’s government (in 1977), hundreds of liquor shops were attacked. But most of the attackers used to come in chanting Islamic slogans, destroyed the shops but instead of breaking the alcohol bottles, looted them for their own consumption!” He said, laughing.

He continued: “Nobody in those days had even heard of drugs like heroin. But look what happened after they banned alcohol?” He asked. “People turned to deadlier substances. Heroin and kupie (inferior whisky) usage spread. Drug mafias came up and crime shot up.”

Apart from the bustling nightclubs and the beaches and shopping areas like Zainab Market, other favorite spots for the free-wheeling tourists were the Kemari fishing harbor, and a large hut colony of fakirs behind Abdullah Shah Ghazi’s shrine in Clifton. It was in the 1970s that the city’s famous “crabbing” scene was first developed for tourists in Kemari.

But was the crime rate in Karachi really that low in those days?

Ghazzanfar Shahid who worked as a librarian at the Soviet Embassy in Karachi says yes. “There used to be infamous ghoondas (hooligans). But they were nothing compared to the hooligans of today. Young men used to get into drunken brawls and gang fights, mostly over women and student politics, but guns were hardly ever used. They used fists, knifes, chains…but nobody ever knew what a TT pistol or a Kalashnikov was.”

Saran Ahmed, 47, an economist and senior manager at a bank agrees: “If you go through the economic stats of the era (1960s-70s), you will find that there was a lot less economic disparity between classes in Pakistan, especially in Karachi. The rat race to outdo one another, even if that meant committing a crime to become rich, basically started in the 1980s when money from Pakistanis working in the Gulf nations started to pour in and when we got involved in the Afghan war.”

He suggests that 1980s was the era that saw the emergence of a growing class of the nuevo-rich (nau-daulti), and society started to transform into something totally new, something more moralistic on the outside by totally amoral on the inside.

Karachi’s politics before the 1980s was vastly different as well. In his book, ‘Political Dynamics of Sindh: 1947-1977,’ Tanvir Ahmed Tahir describes Karachi’s politics (till 1977) as being scattered but lacking in any serious tension. No single political party held sway in the city.

Famous architect and sociologist, Arif Hassan, in his book ‘The Unplanned Revolution,’ suggests that though the city’s Mohajir majority was one of the most socially liberal segments of the population, politically they were conservative.

This political conservatism was born from the Mohajir’s awkward sense of being migrants (from India) and not being the ‘sons of the soil’ (like Sindhis, Punjabis, Baloch and Pushtuns).

In his autobiography, ‘My Journey,’ MQM chief, Altaf Husain explains how the Mohajirs of Karachi ended up supporting right-wing religious parties like the Jamat-i-Islami (JI) and Jamiat Ulema Pakistan (JUP) because it was important for the Mohajirs to invest more in parties talking about Pakistan as a single nation.

Interestingly, in the university and collages of the city, leftist politics thrived, so much so that Karachi became the centre of the left-wing student movement against Ayub Khan’s dictatorship in 1967-68.

Apart from JI and JUP, the other party that managed to find support in the varied city was the PPP, especially in the city’s working-class areas and slums.

After the 1980s, though JI and JUP’s support largely withered away with the rise of MQM (in 1984), the PPP still holds the support it began gathering in areas like Lyari and Malir in the 1970s.

“What a city it was,” remembers Wali Abdullah, who was a student at the University of Karachi from 1972 till 1975. “People just didn’t seem to have any hang-ups. Even the Jamaties (members of Islami Jamiat Taleba) used to have girlfriends!” He laughs.

Wali, now in his early fifties, added: “Today they call Karachi Pakistan’s most liberal and secular city. But they should have seen it in the 1970s. It would shock today’s kids! We used to sit at roadside cafes on Tariq Road and sip chilled beer just like young people today have bun-kebabs outside chaat shops!”

“And yet, no one was judging you,” says Wali. “No one was questioning your faith, religion or ethnicity.”

Of course, things were not always quite as rosy. The 1973-75 oil crises due to Arab-Israel War (1973) considerably slowed down Bhutto’s economic reforms.

Karachi’s Mohajirs became weary of Bhutto’s ‘quota system,’ his failed quasi-socialist nationalisation process, and the (perceived) rise of Sindhi nationalism. Then together with the JI and JUP, Karachiites put the city at the heart of the protest movement against the Bhutto regime.

And anyway, as an era began shutting the sociology and politics of Karachi, an era in the region too was coming to an end.

By 1979, the Hippie Trail years were as good as over. A civil war in Afghanistan and an Islamic Revolution marked the Trail’s closing. Pakistan too started to change. A conservative military dictatorship overthrew the Bhutto government in 1977 and started laying the foundations of a more myopic, violent, and crime-ridden Pakistan.

A Pakistan that is yet to recover, with its largest city becoming a hunting ground for all sorts of misguided and greedy social, sectarian and ethnic engineers.

The views expressed by this blogger and in the following reader comments do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Dawn Media Group.