BEIRUT: Arab League monitors could hardly have confronted more tragic evidence of the bloodshed convulsing Syria than the corpse of a five-year-old boy laid out on a rug in a mosque in the city of Homs.

“His name is Ahmed Mohammed al-Rai,” a man tells the two monitors. “Look at this. This happened despite the presence of the Arab League.”

A mourner then pulls back the white shroud to show a bloodied bandage and a bullet hole in the boy’s back. The scene was captured on an activist’s mobile phone, posted on Youtube.

The deployment of dozens of Arab League peace monitors to Syria was the first international intervention on the ground in nine months of ferociously repressed protests against President Bashar al-Assad’s government.

But if it initially raised hopes among the opposition, the prospects of them bringing an immediate end to the violence were soon shown to be dim.

Three days into the mission, a harassed-looking monitor told a restless crowd in a mosque in the Damascus suburb of Douma: “Our goal is to observe...it is not to remove the president, our aim to is return Syria to peace and security.”

Footage of the incident was broadcast by al-Jazeera.

The crackdown by government forces appears to have gone on unabated since the first monitor teams arrived in Syria, with about 139 anti-government protesters killed across the country, by a Reuters count.

Syrian protesters, opposition leaders and foreign commentators are now questioning the worth of the monitors’ mission, some suggesting it will merely provide a cover for further repression. The appointment of a general from Sudan, a country with a dire human rights record, to lead it has also cast doubt on its integrity.

What it can realistically do to force the Assad government to ease the crackdown and negotiate with the opposition – and what it can do if he refuses – is unclear.

A blow was dealt to the peace mission on Sunday, when an Arab League advisory panel said it should give up in light of the unrelenting bloodshed.

“This is giving the Syrian regime an Arab cover for continuing its inhumane actions under the eyes and ears of the Arab League,” chairman Ali al-Salem al-Dekbas said in Cairo.

The revolt in Syria, ruled by the Assad dynasty for 41 years, broke out last March following the overthrow of Western-backed strongmen in Egypt and Tunisia and the outbreak of uprisings in Libya and elsewhere in the Arab world.

More than 5,000 people have been killed, according to a United Nations estimate, shot by snipers, blasted by tank fire, or victims of torture or summary execution.

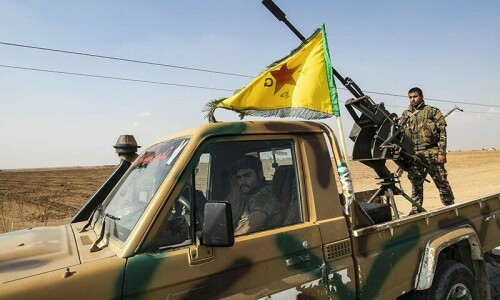

The government blames the violence on foreign-inspired “terrorists” and says more than 2,000 members of its security forces have been killed. Peaceful civilian protests have given way to an armed insurgency led by the Free Syrian Army, whose ranks are filled with army defectors and led by Riad al-Asaad, a former army colonel.

The West, while deploring the violence and imposing sanctions, has resisted an intervention of the sort that hastened Muammar Gaddafi’s end in Libya.

Russia, which has a naval base in Syria and is its main arms supplier, and China also oppose intervention.

But a full-scale civil war could wreak havoc with the strategic balance in the Middle East.

The Arab League, a pan-Arab organisation, took action by suspending Syria and imposing sanctions. The moves were aimed in part at mollifying the various countries’ own populations, who have been enraged by footage of the carnage spread through social media and the Arab tv station al-Jazeera.

The Arab League mission was charged with monitoring a peace plan under which Assad had agreed to pull tanks and troops out of the cities, free detainees and start talks with his opponents. It would also allow in international media, most of whom have been banned from the country, making verification of reported bloodshed difficult.

It got off to a tricky start.

On the day the first monitors arrived in the capital Damascus, army tanks pulverised restive areas of Homs, one of the centres of the revolt, killing about three dozen people, according to the British-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights.

When monitors arrived in Homs the next day, December 28, snipers were posted on roof tops overlooking the rubbish-strewn streets, where pools of blood still dotted the sidewalks. People came out to greet them, only to find the monitors were under a Syrian army escort.

One video clip posted on the internet showed them touring Homs’ Baba Amr district, an area ringed by army checkpoints and sandbagged positions.

Residents shouted at them and tugged at their jackets, pleading with them to enter neighbourhoods to see the destruction that has left whole sections of the city in ruins and led to a virtual state of siege.

Their car was mobbed by people shouting “those who kill their people are traitors”. But many resident refused to speak due to the presence of a Syrian army colonel.

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.