Whether it’s a call on my phone or at the door, I feel scared to death. I mentally prepare myself for the worst, assuming that “they” are here to take me.

But then, when I find a friend at the door or a homeless compatriot asking for food, I realise that it is not my day yet, it is someone else’s.

Despite being unusually lucky, my nightmares don’t end. I rather prepare myself to deal with a situation when Bashar’s sleuths would come to pick me up for writing about the misery of Syrian taxpayers and democracy-lovers.

Regardless of our terrible conditions, we do greet each other daily with ‘sabah al-khair’ or good morning but with little hope for the same.

When I hear stories of torture and disfigured bodies of the missing Syrians and journalists alike, my only prayer to Allah remains, “I am ready for it but ease it on me and my people please.”

We write with pen names and log on the Internet using proxies, thinking we are safe. The reality is otherwise. My missing journalist friends and bloggers had no time to say bye to their loved ones inside the very home they were abducted from. Al-mokhabarat or intelligence agents, just plucked them away, mostly in the dark of the night.

They may discover me sooner or later but I make it a point to erase all my cell phone logs of call and text messages, clear my browser history and empty my laptop’s trash bin. Thinking that I might have forgotten something, sometimes I repeat the act many times a night.

Of late, my personal fear of being kidnapped by government sleuths has been overshadowed by a big, bloodier development. Every day, I see uploaded YouTube videos of the best of Soviet and Russian arsenal knocking down bustling neighborhoods first in Dara’a, then Hama and now Homs.

While I still fear the footsteps of sleuths on my door, I am not being searched as minutely as before.

Instead of looking out for activists and undercover journalists, Bashar’s military is wiping out entire cities from world maps, over suspicions of treason against the Alawite regime.

What started as massacre has duly transformed into genocide. My editors abroad insist on sending my stories with real names, concrete evidence and versions from both sides. I have been in double jeopardy since the first eight months of the uprising when the world only knew about Tahrir square kind of protests.

I, sometimes, wonder if the top-notch media watchdog bodies really know what a faceless and nameless journalist in Syria goes through, at the hands of sleuths as well as the very editors known as gatekeepers.

When making a phone call can risk not only yours and your families’ lives but also the person answering the phone, calling a government source is simply suicidal. Even the most naïve journalist here knows that cellular and landline phone companies are not only owned by the regime’s front-men but also bugged and monitored.

Simultaneously, Syria is a busy place for journalists where one cannot choose which story angle to focus on any given day i.e. massacres in Homs, protests in Damascus and Idlib, Russian FM’s visit to Bashar, or statements from Washington echoing only fake promises.

But in the end the choice won't be mine! The media company decides which one suits its agenda and its geopolitical context. Mostly, the easy bet is to bank on the wire service, ignoring the at-risk on-ground journalist who for them is a mere ‘stringer’!

I felt proud of my profession when I first saw stories by foreign journalists covering Syria from their high risk abodes and makeshift media centers. Though the world would not have believed a Syrian journalist like me for the Bab Amar massacre or siege of Homs but I hope they won’t ignore the outsiders’ testimony.

The natural but tragic death of Anthony Shadid, a Lebanon-born journalist for The New York Times, weighed very heavy on Syrian people’s hearts and the battered country’s image. Syria was referred to as home of death.

Besides dozens if not hundreds of slain Syrian journalists, the uprising has claimed two French media-men, and the one and only Marie Colvin died in more familiar way. Their heartrending deaths came in solidarity with local fellow professionals whose names and faces may be known when the tyrant falls and conscience rules in Syria.

Unluckily, I have many pen names for it is hard to write with a real one. Death of Marie Colvin was personally embarrassing to me. Should I still use pen names when my star colleagues are writing with their warm blood?

I am a single woman with no liabilities except a widowed mother and siblings. One simple story with my real name appearing on an Arabic language blog or English-language website has greater probability of leading sleuths to my home.

Now even my family rarely knows which pen name I use and where in the world, my work publishes. Not that I don’t trust my family but the regime’s four decades of fear can easily cause a Freudian slip.

A year ago, I proudly showed off my byline in international dailies but now we are writing for our lives and not for pride.

I rarely get internet access good enough to open my emails and send my stories in time. I must admit that overall depressing conditions too result in my missing deadlines. Ironically, stories featuring Syrians’ bloodbath are never stale and the desk accepts them more often.

When I work on my laptop, my siblings and mother spy on me to see what I am doing or writing. My eldest sister advised me last September, “I can’t stop a journalist from writing but she should not forget the fate her younger brothers may face if they (mokhabarat) find out.”

One of my university fellows was picked up for writing a blog about a missing seven-year-old in Dara’a. Her brother went to a police station to lodge a report but never returned home. Three weeks later, their mother was asked to receive her son’s body from the same police office. She not only got the body of her 20-year-old son but also discovered the disfigured corpse of her blogger daughter.

Earlier, I hoped to change the world’s opinion with my writings but now, I am only recording testimonies of massacres and detailing current history.

Long after they have taken me to die in their dark cells, my stories will serve as credible evidence to try Bashar and his advisors for crimes against humanity.

Like journalism, we are learning survival techniques on our own, the hard way. Whenever a couple of us sit together away from our parents and the listening walls, we talk about the best ways in dealing with the worst.

I usually tell my colleagues, “Why do you think they would wait for us to admit or defend ourselves. Our charge-sheets are already there with no room for defense or discussion . . . Agents we are! . . . Agents of change!”

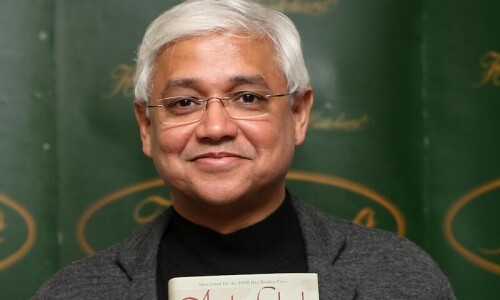

Maryam Hasan is a young journalist, whose family struggled against Hafiz Al-Assad’s tyrannical rule and policies. She is using a pen-name due to security reasons.

The views expressed by this blogger and in the following reader comments do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Dawn Media Group.