THE doctors’ strike which recently concluded presented fascinating insights into the expectations general society has of doctors.

Regardless of which side you took in the debate, it was remarkable to see the level of vitriol and indignation towards the striking doctors prevalent in even the simplest press and television news reports.

And perhaps that comes as no surprise, since a strike by doctors is a far more emotive issue than a strike by, say, road workers or lawyers. Doctors, the logic goes, cannot renege on their duties even in the slightest, for doing so would put lives in danger. But more fundamentally, the reaction was also rooted in a sense of betrayal. Society trusts doctors to cure its ills and take care of it in its weakest physical and psychological states.

Trust is an essential aspect of healthcare, but unfortunately most of us look to doctors and the medical system through a narrow, curative lens. People come to doctors when they need cures, but that is not the sole route to health. The majority of deaths in Pakistan, and indeed across the world, are caused by diseases which can be controlled and defeated through measures that nip them in the bud. These ‘upstream’ measures, which stop diseases from reducing us to statistics, are part of a science known as preventive medicine.

Current healthcare resources concentrate mainly on curing and managing the diseases we suffer from and preventive medicine removes a significant burden from them. It does so by dealing with diseases before they require medication or hospitalisation and by halting the disease process from evolving. In most cases preventive medicine allows your body to either develop resistance to a weakened or dead infective organism (a vaccination, for example), or change the body’s habits in order to break a cycle which would have otherwise led to disease (such as exercising to prevent heart disease). But preventive measures also require greater levels of trust and by extension, responsibility. And herein lies the catch — that responsibility is not the purview of doctors alone.

Take the example of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), which according to the WHO are the leading cause of non-infective deaths in Pakistan. CVDs occur when blood vessels get diseased, damaged or develop clots in different parts of the body, causing a heart attack or stroke, etc which can lead to either death or disease. CVDs may be treated through surgeries or medication, but both carry significant physical and financial consequences and in the case of medications, aren’t even an exact science. Consequently, they are only prescribed as a last resort.

But another reason that their use is delayed is because 80 per cent of CVDs are caused by unhealthy lifestyle choices, and hence the most effective way of treating the disease is to remedy such choices. What that means is that controlling the patient’s risk factors by means of a proper diet and exercise are essential facets of prevention and treatment. To put it simply, preventive medicine saves the cost of expensive procedures and the need to go to a doctor for treatment.

At the same time, though, preventive medical measures also go on to create new webs of trust and responsibilities. Patients not only need to take control of their own health by disciplining their bodies but also need to trust that the medication does its job as well as trusting the food that they buy.

The responsibility for their health is thus further expanded from beyond just themselves to include pharmaceutical companies and even advertisers marketing products under the banner of ‘healthy for your heart’ and other catchy slogans. In essence, a wide network of mutual trust and responsibility is essential for basic health-care practices to be supported and reinforced. Without trust or responsibility, healthcare becomes an increasingly difficult proposition.

Nowhere is this idea of trust (or lack thereof) more clearly elucidated than in the long-standing issue of polio. With no cure available, preventive measures are the only solution and the only hope. Unfortunately, trust in those preventive measures has been eroded due to continuous assaults by a range of actors.

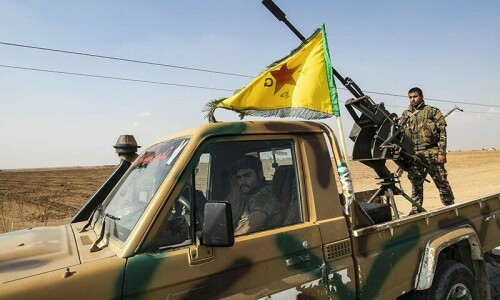

First of all there are the militants who paint the vaccinations as imperialist ploys to render children impotent, spreading these spurious claims via Friday sermons and radio broadcasts. Compounding their efforts was the US government, which was exposed using a hepatitis vaccination programme as a cover for espionage operations, giving credence to the conspiracies hatched by militants.

And even before this recent tit-for-tat between two sides in a state of war, pharmaceutical companies had also greatly contributed to this trust deficit within Pakistan. In 2010, a drug company was caught lying about the contents of its rotavirus vaccine, which prevents diarrhoeal diseases, after it was found to contain traces of pork derivatives — a fact which the pharmaceutical giant first denied and then claimed would not harm the two- to four-month-old children it was meant for, without any proof to support the claim.

Scandals such as these only helped thicken the dense intrigue within Pakistan which now accompanies any debate on polio vaccination. The presence of such conspiracies decimates any sense of trust, which means that preventive medicine is rendered ineffective.

It is important to realise that healthcare is not just a question of available doctors or even the amount of money and resources being used to develop infrastructure. Undoubtedly these issues are crucial, but ultimately trust and responsibility lie at the core of healthcare. The panicked outrage at the doctors’ strike was caused partly because people felt that doctors could not be trusted to provide care. But as the above discussion has shown, trust cannot be placed solely in doctors.

Healthcare solutions rely on a variety of factors, but they must incorporate a sense of responsibility by every concerned stakeholder and trust between each and every one of them.

The writer is a medical doctor and has a master’s in public health.