Like any other country, Pakistan too has been producing geniuses in various fields.

But this piece is not about them.

It is about those highly talented Pakistani men and women who experienced the flip side of genius: i.e. an awkward and often torturous state of mind that some describe as being a kind of madness.

This is a study of Pakistanis whose lives have been touched by a strain of overt brilliance whose cost has sometimes been mental anguish, social isolation and unfulfilled (or only partially realised) talent.

______________________________

Ahmed Parvez

Born in Rawalpindi, Parvez started his career at the Punjab University. A restless soul, Parvez moved to London in 1955.

Parvez was highly motivated to increase awareness of the new developments in painting he witnessed in London and consequently attempted to integrate Modernism into Pakistani art.

In the late 1960s Ahmed returned to Pakistan and moved to Karachi. Across the 1970s Parvez rose to become one of the country’s premier artists and a huge influence in the then thriving art scene of the city.

In spite of being surrounded by young admirers, Parvez remained to be restless and impatient, never satisfied.

His lifestyle became increasingly erratic. Nonchalant about being hailed as a genius by art critics in the UK, US and Pakistan and able to sell well his work, a contemporary noted that Ahmed treated money ‘as if he hated it.’

Most of it was spent on alcohol and this attracted ‘free loaders’. However, sick of the company he was attracting, Ahmed began frequenting the various Sufi shrines of Karachi.

Though he had already experimented with drugs like LSD and hashish in London, he became a habitual hashish user at Karachi’s famous Abdullah Shah Ghazi shrine in the Clifton area.

In fact by the mid-1970s, Ahmed could be seen exchanging hash pipes with fakirs at the shrine. But he continued to paint prolifically.

A 1970 Modernist painting by Ahmad Parvez that was successfully exhibited in various renowned galleries of the UK and the US.

Art critic, Zubaida Agha, in an essay on Ahmed Parvez writes that the more fame Parvez gathered the more erratic and ‘unhealthy’ his lifestyle became.

By the late 1970s he was almost permanently staying at the Abdullah Shah Ghazi shrine.

A Lahore-based artist, Maqbool Ahmed, who was a student at the Lahore College of Arts in the late 1970s, told me how he came to Karachi to meet his idol, Ahmed Parvez, but was shocked at what he found: ‘This was 1978. Parvez was a mess. He didn’t even acknowledge my praise and presence.’

Maqbool said Parvez could have made millions: ‘He did make some money but it seemed he wasn’t interested. He behaved as if he was selling his soul to people who had no clue what his art was all about. Perhaps, it was this guilt that drove him into the hands of the fakirs.’

Even when in 1978 the government bestowed upon him the prestigious Pride of Performance Award, Parvez continued his bizarre lifestyle.

Then it happened. And no one was surprised.

In early 1979, Ahmed was found dead on the grounds of the Abdullah Shah Ghazi shrine. He was 53.

Lamenting Parvez’s self-imposed isolation and destructive lifestyle, an art critic writing for DAWN in 1979 added that ‘Ahmed Parvez still had another 20 years of genius left in him.’

But perhaps, it was this genius that so tragically sealed his fate as well?

______________________________

Saadat Hasan Manto

Today hailed as one of the sharpest and most insightful Urdu short-story writers, Manto reflected the many traits found in the characters he created for his stories: Men and women with a desire to settle in settings that continued to seem alien and even hostile to their mental and emotional dispositions.

Born in colonial India, Manto produced the most compelling stories.

The partition of India into two separate countries baffled him and this bafflement became a regular theme in some of his most enduring short stories.

Though, a progressive in his politics, Manto could not fit into the fold of the famous ‘Progressive Writers Movement’ (PWM) that was churning out literature to initiate socio-political change.

It was the language and the imagery that he used in his stories that many of his progressive contemporaries could not come to terms with. They found them to be ‘crude,’ leaving Manto free to become what he really was: An uncompromising individualist.

Divorced by the ways of the PWM, Manto continued producing stories about misunderstood, and at times painfully inarticulate individuals trying to come to terms with the meaningless violence and the sudden (and at times bizarre) feelings of separation that followed the 1947 partition of India.

Abandoned by his progressive contemporaries, Manto soon found himself facing a barrage of accusations by religious outfits and the government.

In the early 1950s, the religious parties denounced him for producing ‘obscene literature’ as the government (though largely secular) sided with his religious critics.

But Manto was neither obscene nor a part of any revolutionary political struggle. He was just different, and perhaps a bit ahead of his time.

Manto was booked and tried in the court of law six times for supposedly ‘spreading obscenity.’ Though each time he was let off, the experience and also the reception his writings attracted both from the left and the right sides of the ideological divide, significantly contributed to his isolation and his need to drink.

Manto’s stories remained popular with fans of Urdu fiction, but he became increasingly bitter and eccentric. A time came when he was dishing out stories (for magazines) only so he could get paid enough money to buy the cheap whiskey he had become addicted to in Lahore.

Misunderstood, dragged to the courts, harshly critiqued and denounced as being ‘obscene’, Manto literally drank himself to death. He died of liver malfunction in 1955. He was only 42.

______________________________

N M. Rashid (aka Noon Meem Rashid)

A Masters student of Economics at the Government College of Lahore, he spent most of his time working as a civil servant and even served at the United Nations.

His emergence as a poet was slow mainly because he seemed to be leading two separate lives.

One was of a straight-laced, white-collar worker in an expensive three-piece suit and conservative glasses; a calm man who went about serenely chewing a pipe. The other life was that of a highly esoteric poet challenging the conventions of Urdu poetry and ghazal and having a robust (but secret) sexual lifestyle that was at best ambiguous.

Writing about Rashid, literary critic, Prof. Gilani Kamran, says Rashid employed erotic ghazal phraseology for the interpretation of socio-political reality.

It would not be before the late 1960s that Rashid started to be read widely by poetry fans in Pakistan.

He also worked vigorously against the slipping in of Middle Eastern (Arabic) influence in Pakistani culture and strived to retain the region’s historical Persian influence. But it was at this juncture that he suddenly decided to move to the UK.

In 1975, just before his death, Rashid instructed his friends that instead of burying his body, it should be cremated.

That’s exactly what they did when he passed away in 1975, leaving the religious lobbies in Pakistan asking the government to declare Rashid an infidel and ban the sale of books containing his poetry.

As fate would have it, his poetry has enjoyed far more popularity and recognition after his death.

______________________________

Ibn-e-Safi

Ibn-e-Safi was a fascinating phenomenon. A young school teacher in 1952 but raring to make a name for himself as a writer, Safi began writing highly imaginative spy novels.

From 1957 onwards his writing pace more than doubled, and by 1960 he had written over a hundred short novels, all taking place in the imaginary and fantastical world that he had created, full of colourful spies, beautiful women, strange-sounding villains, exotic places and odd gadgets.

But as Safi came up with one exotic story after another, he also began to isolate himself from his family. He eventually collapsed within himself, suffering a serious bout of schizophrenia for which he needed to be committed to a psychiatric ward.

In 1960 his career seemed to be as good as over when he was put on heavy tranquilisers but continued suffering from hallucinations and severe paranoia.

He began to believe that the characters that he had created were real and that the villains among them were conspiring against him.

Shifting back to his home, Safi was patiently nursed back to health by his wife (and a family hakeem).

Amazingly, just three (painful years) later, he was back writing again.

The demand for his spy novels reached new heights (both in Pakistan, as well as India) and he kept producing them with incredible speed.

In another interesting twist, in 1973 Pakistan’s intelligence agency, the ISI, actually invited him on a number of occasions to lecture new ISI recruits on the ‘art of espionage.’

Becoming Pakistan’s best-selling author, one of Safi’s books was also turned into a film in 1974 by producer Hussain Talpur (a maverick film-maker who was also known as ‘Maulana Hippie’).

Despite being a best selling author, Safi perhaps made half the amount of money that he should have mainly due to the crookedness of many of his publishers and his own lack of understanding of the financial sides of his work.

In 1977 a TV series based on his stories was shot by PTV. However, its run was disallowed when the government of Z A. Bhutto was toppled in a reactionary military coup. The reason given by the military regime was that the series was ‘vulgar’.

Safi, who had continued to be on medication, fell ill again.

Three years later in 1980 he passed away, leaving behind a humongous body of work that is still being reproduced. He was 52.

______________________________

Wasim Hasan Raja

But none has been as hard to pin down, elusive and (to his captains), as frustratingly talented as Wasim Raja (elder brother of former Pakistan cricket captain and popular commentator, Ramiz Raja).

Just before the 1987 Cricket World Cup when the then Pakistan cricket captain, Imran Khan, was holding a large (and televised) function to raise funds for his cancer hospital, the Pakistan team joined him on the stage.

The host of the event (late Moin Akhtar) went about with a microphone talking to various players. When he reached Imran, he asked him who he thought was the most talented player he’s ever played with.

Imran smiled and while pointing at Ramiz Raja said: ‘His brother, Wasim Raja. He was hugely talented, but very erratic.’

Even in his book, ‘An All Round View’ (1994), Khan writes that Wasim never did justice to his stunning talent.

Coming from a highly educated family of Lahore, Raja made his Test debut in 1973, selected for his prodigious cricketing talents.

But throughout his career he remained to be a rebel and a loner. He continued to have a problematic relationship with almost all of his captains and the Pakistan cricket board.

Perhaps the only captain that was able to nurture his talent the most was Mushtaq Muhammad under whom Raja played his finest cricket.

In an essay written by West Indian batsman and former captain, Rohan Kanahi, after his team’s 1975 tour of Pakistan, Kanahi was highly impressed by the swashbuckling batting talents of Raja.

But Kanhai was once surprised to see Raja sitting alone at the bar during a party in Karachi: ‘He was not very easy to talk to,’ Kanhai wrote. ‘He was very private and detached from the rest of the team.’

But the crowds loved him. During the second Test against the visiting Windies in Karachi (in 1975), while fielding near the boundary line, Raja baited a section of the large crowd at the National Stadium by teasingly threatening to unzip his fly! Outraged, the conservative Urdu press accused him of being drunk on the field. Raja, however, went on to crack a superb century in the match.

Pushed in and out of the team for his cavalier approach, Raja was not played in the 1976 series against New Zealand that Pakistan won 2-0 (under Mushtaq).

His name was missing again from the 18-member squad that was announced for Pakistan’s long tour of Australia and the West Indies. Both teams at the time were considered to be the best in the world.

However, on the insistence of captain, Mushtaq Muhammad, and manager, Omar Kureshi, Raja was finally given a berth in the touring squad.

In spite of performing well in the side games, Raja could not find a place in the playing eleven in the 3-Test series against Australia (that Pakistan drew 1-1).

Raja had scored a scorching century against a tough Queensland side, but when the night before the third Test he was told by the team manager (Col. Sujja) that he will not be picked for the Test, Raja went on a rampage.

Always a reckless drinker but painfully introverted, Raja decided to express his rage by smashing all the mirrors in his hotel room (with a whiskey bottle). He then stumbled into the hotel lobby, slurring abuses against Sujja.

In his autobiography, Mushtaq Muhammad relates how some players, who were having a drink at the hotel bar, panicked and approached Mushtaq, and it was left to the captain to cool Raja down. Mushtaq also suggests that Sujja actually wanted Raja in the playing eleven, but it was Mushtaq who decided to play Haroon Rashid instead.

The management decided to send Raja back to Pakistan, but Mushtaq vetoed the decision.

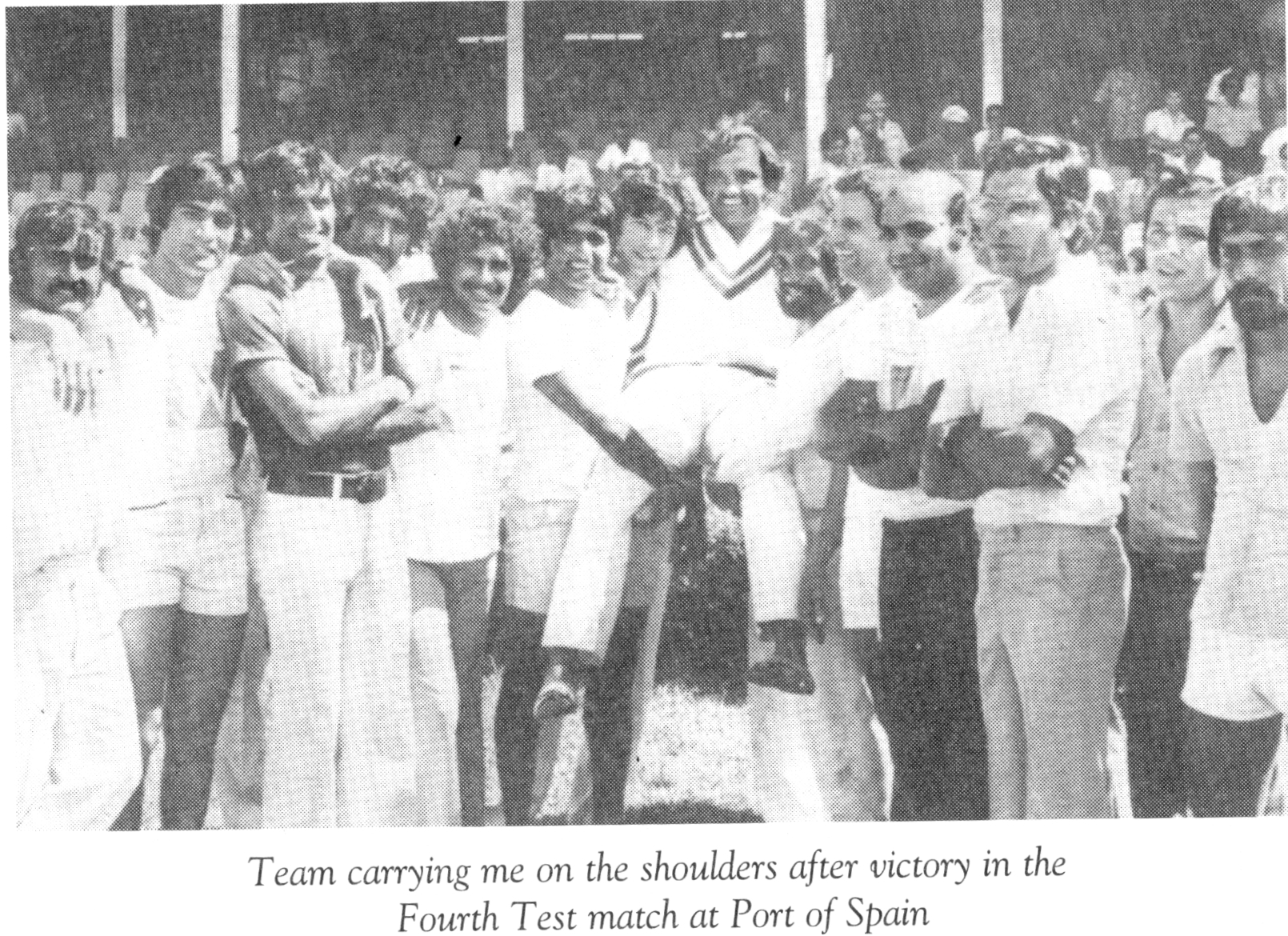

Raja finally got his chance in the West Indies leg of the tour, on faster wickets and against faster bowlers. In a closely contested 5-Test series (that the Windies won 2-1), Raja compiled over 500 runs, cracking one century and five fifties (and hitting 14 sixes – a record at the time of a batsman hitting the most sixes in a series).

A Pakistani player fondly remembered how Raja (during the fourth Test) sat in the dressing room in his shorts, then casually walked out to smoke ganja with some West Indian fans, came back, padded up, went in and hit the fearsome fast bowler, Joel Garner, for a first ball six over long-off!

In his book, Mushtaq writes that he continued to tolerate Raja’s ‘many eccentricities’ because he was performing brilliantly.

After five top Pakistanis opted to play for Kerry Pecker’s World Series Cricket in Australia (they were consequently banned by the Pakistani board), Raja’s name came up to take over the team’s captaincy.

But his volatile personality and cavalier approach made the board give the position to Wasim Bari.

Then when the banned players returned for the 1978 series against India, Raja was dropped yet again. However, he found himself back in the team for Pakistan’s exhaustive six-Test tour of India in 1979. By now Asif Iqbal had (controversially) replaced Mushtaq as skipper.

Having no clue how to handle the team’s two brilliant but erratic and mercurial players, Sarfraz Nawaz and Raja, Asif had a falling out with Nawaz who refused to play under him. But Asif decided to take along Raja.

As Pakistan’s top batsmen all struggled on the tour and the team’s premier fast bowler, Imran Khan, found himself in the quagmire of fixing his troubled back and fending off rumours of him having a torrid affair with Bollywood actress, Zeenat Aman, Raja decided to have a ball.

Though Pakistan lost the series 2-0, Raja scored over 500 runs in the series, throwing caution to the wind and always in danger of being dropped for not heeding the captain’s advice.

Raja carried his good form under new captain, Javed Miandad, even though Miandad confessed that it was always a tussle to reign-in Raja’s impulsiveness and detached demeanour.

Veteran sports journalist, Iqbal Munir, explained Raja as an ‘angry young man,’ who was always hard to understand and, in fact, actually did not want to be understood.

Raja hardly had any close friends in the team. Comparatively speaking, the only player he did somewhat get along with was fast bowler, Sarfraz Nawaz, himself a volatile and erratic figure.

Raja continued to baffle the selectors and captains and constantly lost his position in the side until he finally bid farewell to cricket in 1986.

Former Pakistan captain Imran Khan suggested that Raja was brimming with extraordinary talent, but his detached attitude, and his temperamental and loner personality stopped him from realising his true potential and become a constant part of a unit.

Raja moved to the UK to become a teacher. He died there at the age of just 54.

______________________________

Roohi Bano

‘A real genius,’ this is how famous author and playwright, Ashfaq Ahmed, once described Pakistan’s TV and film actress, Roohi Bano.

Bano was the most sort-after TV actress in the 1970s. Along with Uzma Gillani, late Khalida Riasat, Madeeha Gauhar, (and, to a certain extent, Sameena Pirzada), defined and almost perfected the art of serious TV acting for a host of Pakistani TV actresses that followed.

But Bano remained to be the finest in this league because even though she acted (as a heroine in a few films), and also took some light roles, producers and writers struggling to bring to the mini-screen plays by intellectual heavyweights, always chose her as their leading lady.

The reason was simple: She could seamlessly immerse herself in roles that were constructed to express awkward psychological and emotional complexities.

That’s why her most compelling moments can be found in TV plays scripted by Ashfaq Ahmad in the 1970s – a time when the author himself was struggling to come to terms with his own intellectual and existential crises, trying to figure out a path between the free-wheeling liberal zeitgeist of the period, populist socialism and Sufism.

Very few of Bano’s fans knew that the psychologically scarred roles that she was playing so convincingly were also reflecting what was going on in her own life.

By the early 1980s, Bano, who had been such a popular and respected mainstay on TV in the 1970s, was only rarely seen on the mini-screen.

It transpired that she’d been having serious psychological issues throughout the 1970s and had to be committed to a psychiatric hospital for treatment.

She was still only in her 20s when she began suffering serious psychiatric problems that hastened her disappearance from the screen.

Her condition only worsened when TV plays began facing heavy censorship during the Ziaul Haq dictatorship and she kept turning down ‘sanitised roles.’

And when (in 1988), she did return to the screen (after the demise of the Zia regime), her fans could hardly recognise her. She seemed to have aged rapidly and looked exhausted.

Her great comeback never materialised. After just a few plays she went back on heavy medication and suffered another series of breakdowns.

Today, she leads a reclusive life in Lahore, while her fans still long for that great comeback that she was expected to make many years ago.

______________________________

Haroon Rahim

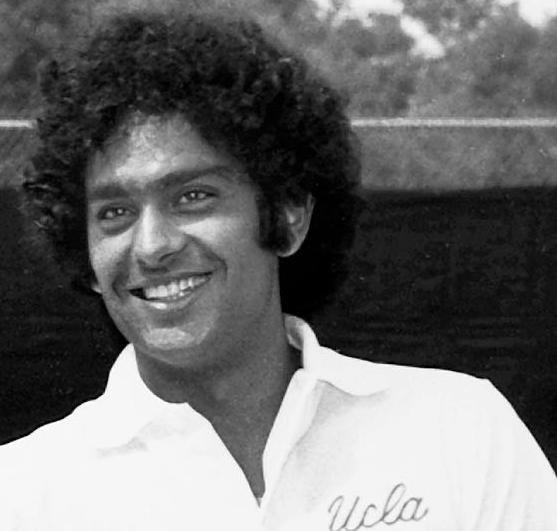

Long before there was Pakistani tennis star, Aisamul Haq, there was the mercurial, Haroon Rahim.

Only a few tennis enthusiasts remember him today. But he made quite a name for himself some 40 years ago when he represented Pakistan in the Davis Cup at the young age of just 15.

A tennis prodigy, Rahim rapidly rose to become Pakistan’s No: 1. At age 20 he was given a scholarship by the prestigious University of California (UCLA) where he became the captain of the university’s tennis team and led and partnered future World No:1 Jimmy Connors in many tournaments.

He remains to be the only Pakistani player to have made it to the quarterfinals of the highly competitive US Open (in 1975). He also defeated famous Wimbledon winners, Jimmy Connors and Arthur Ash.

Rahim continued representing Pakistan, (and it was due to him that various famous tennis stars visited the country for matches in the 1970s). But his personal life wasn’t always that glorious.

Though coming from a highly educated and well-to-do family, Rahim was constantly rebelling against his family’s aristocratic background.

More and more he began to spend time in the United States. In 1978, while at the peak of his game, Rahim met and married an American woman. This did not go down well with his family who refused to acknowledge the union.

Angered by the reaction, he cut off all ties with the family. Not only did he do that, he also quit tennis and simply vanished. He was just 29 at the time.

Some believe that he joined a roving cult in California, sold all his possessions, changed his name and appearance and just disappeared.

Whatever the case, he was never heard from (or found) again – even though his family believes he’s still living in the US (under a new name and identity).

The views expressed by this blogger and in the following reader comments do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Dawn Media Group.