The Fall of Dhaka, as this moment in history is also known, resulted in the surrender of almost 93,000 Pakistani army men stationed there to the Indian armed forces. Retired major Mohammad Iqbal Mirza was one of them.

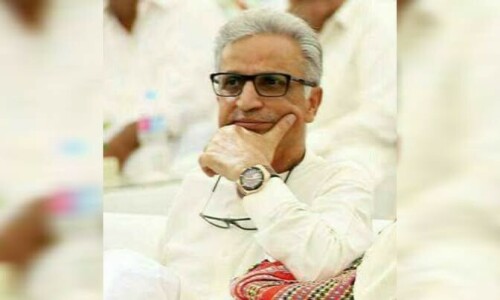

He was in his forties back then. Now at the age of 88, retired major Mirza is a tall lean man who believes in going on water fasts and fruit diets. They must be working because he is an incredibly active man and appears quite healthy. He seems unaffected by any of the frailties of old age. He was a prisoner of war in India for almost three years.

He was commissioned to go to East Pakistan right before the war broke out. He was stationed in the Martial Law Headquarters in East Pakistan. “I was a part of the administration focused inside the cities,” he related, “although I believe our soldiers who were on the frontlines fought very bravely.”

What was it like living as a West Pakistani army man in East Pakistan at that time? “I was afraid of going to sleep. I would spend my nights sitting in a chair with a grenade in my hand.” Why? “Because of the Mukti Bahini of course!” he exclaimed, talking about the guerrilla group in Bangladesh that fought the Pakistani army stationed there. “We had nothing to be afraid of during the day as they never dared to attack in broad daylight,” he said emphatically, “They usually attacked at night, under the cover of darkness.”

Following the fall of Dhaka, he was one of the 93,000 army troops who surrendered as POWs to the Indian army. They were held in camps with barbed wire boundary walls. The Indian troops would patrol the boundaries at night with watchdogs.

Despite all these measures there were quite a few successful escapes.

What was the worst that could happen? “That you could either be shot or your nails could be pulled out,” he said gesturing with his hands to depict the latter consequence, “but that usually happened only if you tried to escape from the camp.”

Did a lot of prisoners of war attempt to escape? “Oh yes. Not officers who were as old as I was.” You were in your forties, that is not old? “It is by army standards. It was mostly younger officers who would attempt to escape. You tend to take more risks when you’re young. We knew there were several people who were trying to dig a secret tunnel. They would cover the opening up whenever they weren’t digging or when they felt it would be discovered.”

Did it work? “No. Unfortunately, the tunnel they were digging caved in. But we had heard that in the camp beside ours, several people had managed to successfully build a tunnel and they escaped.

“Two men managed to escape from our camp. They were a little crazy if you ask me. They were young men who broke through and climbed over the barbed wire walls around our camp. Their hands were badly injured and they had cuts all over their bodies. Unfortunately, when they got out, they ran into a check post run by Indian soldiers and were caught. The soldiers shot one of them and returned the other alive to tell the story.”

But there were exceptions to the ‘good’ manner in which the Indian army treated the POWs. “Indian senior army officers used to come to our camp once a month and give us a talk on discipline and matters of their interest,” he said, and went on to relate an episode where, during one such session, a Pakistani army man lost his temper and spoke rudely to the Indian officers. He was later taken away, beaten up and put in a small cell where they stored hand grenades; there was only enough room for one man to stand. The Pakistani prisoner had to stand perfectly still the entire night or risk being blown up. “The officer on his return couldn’t walk or move properly for almost ten days,” Mirza remembers.

Overall, however, the prisoners were treated well; they were kept in accordance with Geneva conventions and everything was fine as long as they behaved themselves and did not try to escape. “There was a section where women and children prisoners of war were kept and we asked that one of our meals (we were given a sepoy’s ration of pulses, vegetables and mutton) that included meat be distributed to them — as army personnel we had greater privileges than they did. The war was costing the Indian government heavily in monetary terms!”

The Simla Agreement signed between India and Pakistan on July 2, 1972 laid down the rules that the two countries would follow when governing their future conduct with each other. The original agreement, however, did not mention any POWs.

In 1973, a supplementary Simla agreement on repatriation was signed upon which India released almost 90,000 POWs and allowed them to return to Pakistan.

When retired major Mirza returned, Lahore was his first stop. Everyone who returned had to submit an account of their experience and observations about their colleagues at camp. Anybody under the slightest suspicion of being ‘turned’ by the Indian army was essentially fired from service.

“Yes, some might have used this opportunity to settle a personal vendetta. Someone, who had an issue with me at camp, once complained that I frequented the offices of the Indian soldiers regularly. I was fond of reading and the Pakistani officer I would register my requests to would direct me to the relevant department to select the books I wanted. I was questioned about it, I responded honestly. I always followed protocol and there were people who could vouch for me, so I didn’t get into any trouble.

“Throughout the time I was away as a prisoner of war, the Pakistani army paid my monthly salary to my family and took care of them. After returning to Pakistan, I got to go home for a month as a ‘vacation’ and was then commissioned the Karakoram highway near the China border. Life went back to normal once we came back to Pakistan.”