In this fifth installment of our ‘Crazy Diamonds’ series, we continue our tributary look at those promising Pakistanis who experienced the flip side of genius – an awkward state of being that some describe as a kind of madness.

Previous Parts: Crazy Diamonds – I Crazy Diamonds – II Crazy Diamonds – III Crazy Diamonds – IV

____________________________

Aziz Mian

With long, unkempt hair, colourful kameez-shalwar and wild eyes he could’ve been one of the many fakirs or even a homeless vagabond, who for centuries have frequented the famous shrine.

But he was no ordinary fakir. People knew him as a young qawwal – or the singer and performer of Sufi devotional poetry and music, the qawwali.

People who often saw this young qawwal at the shrine also knew that he was highly educated. He was Aziz Mian. The man who would rise to become not only one of the most famous qawwals in Pakistan, but also perhaps the most unique and controversial.

It would be the qawwali that he wrote on a crumpled piece of paper on the grounds of the Ganj Bakhsh shrine that day that would lift his status and popularity to unprecedented heights.

Unlike most qawwals, Aziz Mian almost always wrote his own lyrics. And the lyrics that he scribbled at the shrine became the words to the epic qawwali, ‘Mein Sharabi’ (I’m an alcoholic).

After the qawwali hit the music stores, it became an instant smash, and Aziz Mian was no more a struggling young qawwal looking for an opening.

Born in 1942 in a lower-middle-class family in Delhi, Aziz Mian migrated to the newly created country of Pakistan in 1947.

Coming from a musical family, Aziz Mian began learning qawwali from the age of 10 at the Ganj Bakhsh shrine.

He started to drink, smoke and became addicted to strong, tobacco-laced paans at an early age, and was often arrested for committing petty crimes of vandalism and hooliganism as a teen.

Though restless and quarrelsome, he, however, managed to excel at school and then (in the early 1960s) went on to pick up multiple degrees in Urdu, Persian and Arabic literature from the Punjab University in Lahore.

Though he had been performing live and had already cut a few albums, it wasn’t until EMI-Pakistan released the first version of ‘Sharabi’ (in 1973) that Aziz Mian shot to fame.

On ‘Sharabi’, Aziz Mian also discovered and stamped a style of writing, composing and vocal delivery that he would retain for the rest of his career.

Taking the approach of the ‘quarrelsome Sufis/Fakirs’ of yore who in their state of reverse trance undertook loud emotional dialogues with God, dotted with a series of paradoxical questions, Aziz Mian would start slowly, break into a catchy chorus with his ‘qawwali party’ (qawwali group), and then suddenly stop and shout out his argument in a blistering display of speed-talking in which he would address God, complaining how he loved him but felt that he wasn’t being loved back; or why such a perfect entity like God would create such an imperfect creature like man!

Aziz Mian was a heavy drinker, and like various famous Sufi poets he often used the state of drunkenness as a metaphor for the state and kind of effect the love for God had on him.

But he would also praise alcohol on its own terms.

By the mid-1970s Aziz Mian had risen to become the region’s leading qawwal and was selling out concerts across Pakistan and India.

However, many of his concerts used to also disintegrate into becoming drunken brawls when Aziz Mian would purposely work up the audience into a state in which many among the crowd would lose all sense of order and control.

He would explain this as being a stage from where the brawling men could take the leap into the next stage of making a direct spiritual connection with the Almighty.

A cultural writer reviewing one such Aziz Mian concert in Karachi in 1975 described him as being ‘the Nietzschean Sufi!’

Aziz Mian also benefitted from the cultural policies of the first PPP regime of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (1972-77).

The policies instructed state media to regularly telecast folk music and qawwali on TV and radio, especially during a weekly show called ‘Lok Virsa’ that became a huge hit with the audiences.

This also helped another group of qawwals become equally popular. These were the ‘Sabri Brothers.’

The Sabri Brothers were a lot more melodic and hypnotic in their style and began drawing huge crowds. Soon, a rivalry began to develop between Aziz Mian and the Brothers.

The Brothers often mocked Aziz Mian of being violent and lacking melody. But Aziz Mian went on honing his unique style.

Aziz Mian and the Sabri Brothers both stood for the same Sufi traditions that had developed in the region, but the Brothers disapproved of Aziz Mian’s praise of wine in his qawwalis – even though alcohol was often consumed at the Brothers’ concerts as well.

The rivalry between Aziz Mian and the Sabri Brothers took a more aggressive turn when in 1975 both released their biggest hits to date.

Aziz Mian extended ‘Saharabi’ by adding another 30 minutes to the qawwali until it became an almost 50-munute epic called ‘Mein Sharabi/Teri Soorat’ (I’m an Alcoholic/Your Face).

The record, released by EMI-Pakistan, sold millions within months.

The same year the Sabri Brothers released ‘Bhar Doh Jholi’ (Fill My Bag) that also became a massive seller especially when it was chosen as a song for popular Pakistani actor, Muhammad Ali’s 1975 hit film, ‘Bin Badal Barsat.’

The Brothers also appeared in the film singing the qawwali at a shrine where Ali’s character is shown with his wife (Zeba), pleading the Sufi saint buried there to ask God to grant them a child.

Aziz Mian thought the Brothers were too conventional and that their spiritual connection with the Almighty was not as stark as his.

In 1976 Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto invited Aziz Mian to perform for him in Islamabad and share a drink. Aziz Mian gladly obliged.

As Aziz Mian was enjoying another burst of popularity and commercial success with ‘Mein Sharabi/Teri Soorat,’ the Sabri Brothers followed up their hit ‘Bhar Doh Jholi’ with a thinly veiled taunt at Aziz Mian.

They released ‘O Sharabi, chor dey peena’ (Hey, Alcoholic, Stop Drinking’).

The qawwali became an immediate hit, sung in the typically steady, controlled and hypnotic style of the Brothers.

Aziz Mian was quick to retaliate. He wrote and recorded ‘Hai kambakht, tu nein pe hi nahi’ (Unfortunate men, you never even drank!) in which he mocked the Brothers for not understanding and experiencing the ‘spiritual sides of wine.’

Pakistani qawwali had reached a commercial peak and then went global when both Aziz Mian and the Sabri Brothers began touring outside Pakistan, enthralling audiences in various countries.

Aziz Mian fell on the wrong side of the law when in April 1977 sale of alcoholic beverages (to Muslims) in Pakistan was banned.

During the reactionary Ziaul Haq dictatorship (1977-88), Aziz Mian’s concerts were often raided by the police and people arrested for ‘drunken behaviour.’

From 1980 onwards, Aziz Mian would add more conventional and religious qawwalis to his set list but always wrapped up his concerts with ‘Mein Sharabi.’

However, now he would launch into the qawwali by laughingly and jokingly addressing the crowd (in Punjabi), saying, ‘I’m about to sing ‘Mein Saharbi’ (crowd would roar). But you guys don’t have to worry. They’ll arrest me, not you!’ (Crowds would burst into laughter).

On a number of occasions Aziz Mian was approached by anti-Zia student and political outfits to release a qawwali against Zia.

Instead he decided to add extempore lyrics to his famous qawwalis that spoke about how men intoxicated by their love of God and justice stood up to tyrants who had no understanding and appreciation of this unique kind of love.

During a small concert in Karachi where Aziz Mian had been invited to perform, he noticed some policemen inside the venue.

Believing they would begin harassing the gathering the moment he launched into his ‘pro-wine’ qawwalis, he decided to test the patience of the cops by singing what became the longest qawwali recorded in the history of the genre.

Beginning the concert with the passionate ‘Allah hee jannay kon bashar hai’ (Only God knows who is human), he then launched into ‘Hasshar kay roz yeh poochon ga’ (On the Day of Judgement, I shall ask) - a qawwali that went on for 115 minutes!

Recorded at the venue and then released, the epic qawwali talks about God inquiring man about his (man’s) hypocrisies. Aziz Mian taunts the puritans who call him a drunk by suggesting that in reality they were the ones who were drunk on things that were far more sinister than alcohol: Power, hypocrisy, prejudice and myopia.

But by the time the Zia dictatorship ended (1988), Pakistan’s first ‘Gold Age of Qawwali’ was already over.

Frustrated by not being able to play enough concerts and record a lot more albums in Pakistan in the 1980s, Aziz Mian’s drinking problem got worse.

In the late 1980s both Aziz Mian and Sabri Brothers were directly challenged by a little known qawwal who would go on to regenerate the qawwali genre in Pakistan and once again turn it into a popular global phenomenon.

Nusrat Fateh Ali dominated the qawwali scene across the 1990s, selling albums and playing to packed audiences around the world. But like Aziz Mian, he too had a passionate ‘love affair with wine.’ He died of liver failure in 1997.

In 1994 Ghulam Farid of the Sabri Brothers passed away. Aziz Mian continued to perform throughout the 1990s but the rise of a new batch of qawwals lead by Nusrat Fateh Ali never allowed him the space to make his comeback and regain the popularity and commercial success that he had enjoyed between 1973 and 1982.

With his liver failing, Aziz Mian continued to drink. Exhausted and ailing, he died during a tour of Iran in 2000 at the age of 56.

____________________________

Ameen Lakhani

His name was Amin Lakhani – a kid who had risen to play first-class cricket from the congested streets of Karachi and inducted into the Karachi University team by famous cricket coach, late Master Aziz, who had plucked him after watching him perform at a club game.

Lakhani had only played a handful of first-class games when he was inducted into the Pakistan Universities XI to play a side match against the visiting Indian Test side led by Bishen Singh Bedi.

But Lakhani taking 12 wickets in the game against a strong Indian batting line-up was not what put him in the news.

The thing that turned him into a sudden star was that in the match he became only the eighth bowler in cricket’s long history to grab a ‘double hat trick.’

His two six wicket hauls in the 3-day game included a hat trick each. Or hat tricks in two consecutive innings.

At once this shy, unassuming and obscure teenager was thrown into the limelight.

Not only was he selected in the 14-member squad announced for the third Test match of the series, he was offered lucrative advertising contracts by multinationals, invited for interviews on radio and TV, and showered with gifts from the cricket board, fans and even by the Indian captain.

It was a startling turnaround for a kid whose father had struggled to keep him at school, and who was simply lingering on the fringes of Karachi’s cricket.

The performance also bagged him a playing contract and a regular salary from Habib Bank.

Enjoying his sudden fame, surrounded by new-found fans and gifts, Lakhani joined the big boys in the Pakistan team for the Karachi Test of the 3-match series.

Sure to be selected in the final XI, Lakhani was training hard in the nets with the team when disaster struck. He fractured a finger.

At least that’s what the team management said when press reporters inquired why Lakhani was not in the final side.

The press didn’t buy the story, but it couldn’t ask Lakhani because the team management had put a restriction on team members talking to the press without first getting the management’s consent.

Nevertheless, since he had already become a sensation, Lakhani was greeted with a loud roar from the 40,000-strong crowd at Karachi’s National Stadium when he entered the playing area (as the 12th man) during the game’s first drink break. His finger was not bandaged and seemed fine.

After polishing off the visiting Indians 2-0, captain Mushtaq Muhammad’s Pakistan team was scheduled to tour New Zealand and Australia.

It was almost certain that the young 18-year-old sensation would be part of the touring squad. He wasn’t.

The press was up in arms again. The management sited Lakhani’s ‘injured finger’ and the fact that he needed a bit more experience.

However, it is also believed that Lakhani ‘lost focus’ after being thrown so suddenly into the limelight.

A teammate of Lakhani’s in the latter’s club side in Karachi, Haroon Nazim, told me that Lakhani who had been painfully shy around girls at school, was overwhelmed when he began receiving ‘romantic’ fan mail from young women.

‘He was shown all kinds of dreams by those who wanted him to feature in ads and magazine covers,’ Nazim said. ‘He began to think that he was well on his way to becoming a rich and famous cricket star.’

But as the team left for the New Zealand and Australia tour, within a matter of months the advertising contracts that were offered to Lakhani were withdrawn, the sudden fan mail stopped, the press lost interest and it seemed Lakhani had vanished from the scene as quickly as he had appeared.

Angry, confused and bitter, the young boy fell into depression. Though he continued to play some first-class cricket till about the early 1980s, people had all but forgotten about him.

He was only in his early 20s when he simply dropped out and ‘retired’ from the game.

His name continued to shine brightly in the record books, but his dream of becoming a cricketing star and of turning over the fate and fortunate of his struggling family simply withered away.

After falling in and out of depression and holding and losing various non-cricketing jobs throughout the 1980s, Lakhani is said to have ‘found peace’ by joining the Islamic evangelical organisation, the Tableeghi Jammat, in the 1990s.

Today he lives a quiet and modest life in Karachi, perhaps still wondering exactly who decided that he had a ‘broken finger’ that fateful day?

____________________________

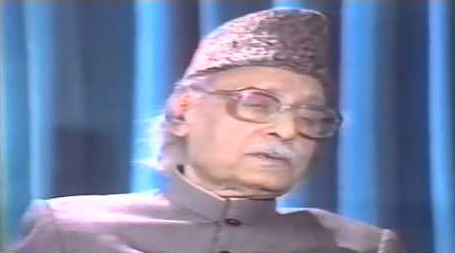

Ghulam Ahmed Parvez

As a young teen in Batala, India, Ghulam Ahmed Parvez often wondered why all the hectic practicing of Islamic rituals and traditions by his fellow Muslims was not producing good men and a better community.

‘Why isn’t all this creating the kind of society that the Qu’ran talks about?’ He would often enquire, more than rhetorically.

Hushed by his elders and treated suspiciously by his friends, Parvez refused to stop looking for answers to the ever-increasing number of questions growing in his head.

He continued to study the Qu’ran and other Islamic literature under various religious scholars, while at the same time also attending a Missionary school in Batala. He then went on to bag a Master's degree from the Punjab University in 1934.

After mastering the works of some of Islam’s leading scholars and texts, Parvez moved towards studying the faith’s esoteric strains such as Sufism and Tasawaaf (Islamic mysticism).

During this period he also managed to meet renowned poet and philosopher, Muhammad Iqbal. Taking Iqbal to be his mentor, he held many discussions with the poet, especially on Islamic philosophy and the Qu’ran.

His relationship with Iqbal helped the young Parvez come into contact with the head of the All India Muslim League (AIML), Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

By the time Jinnah had asked Parvez to edit and publish a pro-AIML Urdu weekly, ‘Talou-e-Islam,’ Parvez had already began to formulate and advocate his views on the subject of Islam in the subcontinent.

He claimed that Islam (unlike other monolithic faiths) was not supposed to be an organised religion. Undermining the importance of Islamic rituals, Parvez said the Qu’ran is an ideology and a philosophy beyond rituals and that anything practiced or believed by Muslims that was outside the Qu’ran was a fabrication.

Parvez was particularly harsh on the traditional Islamic institution and ‘science’ of Hadith (sayings attributed to the Prophet and his companions and reported by a chain of men years after the Prophet’s demise).

According to Parvez a majority of Hadiths (upon which a bulk of Islamic Laws in the Shariah are built and based up on), were fabrications authorised by Muslim kings to justify their tyrannies and by anti-Islam forces who wanted to portray the faith as being amoral and violent.

Parvez had become a prominent ‘Quranist’ – someone who rejected the religious authority of the Hadith or of any Islamic text that was not part of the Qu’ran.

Though he was immediately attacked and labelled as a heretic by traditional Islamic scholars and religious parties like the Jamat-i-Islami, Ahrar-e-Islam and Jamiat Ulema Islam, Jinnah insisted that Parvez was to be the one to edit ‘Talou-e-Islam’.

In a two-pronged strategy, Parvez used the magazine to propagate the implementation of Jinnah’s principle that had inspired the demand for a separate Muslim State; and to blunt the protests of the conservative Islamic forces that had dismissed Jinnah’s demand for Pakistan. They accused Jinnah and his party of being too secular and ‘modernist.’

One of the first cover features to appear in the magazine was titled, ‘Mullahs have hijacked Islam.’ In it Parvez lambasted conservative Islamic parties and the molvies as being ‘agents of rich men’ and the enemies of the well being and enlightenment of the common people.

On the eve of Pakistan’s independence in August 1947, Parvez had become a close advisor of Jinnah.

He became part of the Muslim League government after independence, but retired in 1956 to concentrate on his scholarly work.

In 1961, Parvez attempted to popularise saying the Muslim prayers (namaaz) in Urdu, a language he said most Pakistanis understood (unlike Arabic).

In the 1930s, Turkey’s Kamal Atta Turk had attempted to introduce prayers and the call for prayer (aazan) in Turkish.

Though the move was initially supported by the secular Ayub Khan regime (1959-69), Ayub backed out when Parvez was vehemently attacked by conservative religious parties and scholars.

As an author and scholar, Parvez was most prolific. Undeterred by the continuing criticism and threats coming his way by religious parties and conservative Islamic scholars, Parvez kept emphasising and propagating his Quranist views through a number of books and lectures.

In the 1960s when a group of young leftist intellectuals led by Hanif Ramay and Safdar Mir were working on a theoretical and ideological project to fuse and merge socialism with the Quranic concepts of justice and equality, they incorporated a number of ideas first aired by Ghulam Ahmed Parvez.

The group would go on to join the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) in 1967.

Throughout his career as a Quranist and scholar in Pakistan, Parvez not only managed to invite the wrath of the conservatives within Pakistan, but in some other Muslim countries as well.

In the 1970s his books were banned in various Arab states, especially the UAE and Saudi Arabia that were (and still are) ruled by monarchies belonging to the ‘Wahabi’ strain of Islam that adheres to the strict 8th century Hadith-centric Hannibali Fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence).

Parvez responded to the bans by accusing the monarchies of behaving like ancient Muslim Kings who had used ‘fabricated hadiths’ to justify their rule, subjugate the people, and demonise their opponents.

During the same period, Parvez even began to upset some of his supporters as well, mainly a few ‘progressive Islamic scholars’ who thought his writing style was too abrasive and arrogant and that he was too much in favour of using Quranic concepts to create a political ideology, albeit a leftist one.

It is still unknown though exactly what Parvez’s views were about the 1953 and 1974 riots against the Ahmadis, even though he maintained that Quran does not allow one Muslim to judge the beliefs of another Muslim.

Parvez’s ‘progressive’ stage lasted till about the late 1970s in which he continued to reject the Hadith; the overemphasis of Muslims on rituals; and insisted that rituals and Shariah laws based on the Hadith were contrary to the revolutionary, as well as the rational spirit of the Qu’ran.

From the late 1970s onwards (and after the fall of the left-leaning government of Z A. Bhutto in a reactionary military coup in 1977), his writings and views had already begun to move away from his Islamic interpretations of socialism.

His detractors now accused him of being ‘pro-West’ when he suggested that modern-day scientists were closer to Qu’ran’s emphasis of enquiry and progress than the ulema.

Though still related to by many labour unions as a pro-workers Islamic scholar, he was, however, attacked with shoes in 1978 during a lecture that he was delivering at a function organised by the Mughalpura Railway Workers Union.

His supporters claimed that the attack was provoked by the ‘agents of the Jamat-i-Islami’, a party that had joined military dictator Ziaul Haq’s first cabinet.

Though Ziaul Haq was an ardent follower of conservative Islamic scholar and founder of Jamat-i-Islami, Abul Ala Mauddudi, he resisted the demands of Islamic outfits to declare Parvez and his followers are heretics.

Maybe Zia had already sensed that Parvez was getting old and soft and posed no threat to Zia’s ‘Islamisation’ project.

In the early 1980s when Parvez entered the 80th year of his life, he began to rediscover the early Sufist teachings his father had taught him - though he never reverted his position and views on the Hadith.

In 1983, he decided to visit Makkah to perform Haj and he did that by refusing to wear any footwear whatsoever throughout the trip. He roamed the streets of Madina barefooted.

In spite of the fact that the Zia regime discouraged bookstores to sell his books and Parvez was now too old to give lectures, his previous lectures began appearing on audio-cassettes and the books were clandestinely sold, bagging him a strong but quiet following of Quranists.

But Parvez was slipping into gloominess, and in 1985 he quietly died at the age of 83. The news of his death was only briefly reported in the press.

____________________________

The London Group

A rudimentary ‘study circle’ was formed in London (in 1969) by some Marxist Pakistani students studying in colleges and universities there.

There were about 25 such students in the group who used to meet to discuss various left-wing movements and literature.

They also began publishing a magazine called ‘Pakistan Zindabad’ that (in 1971) had to be smuggled into Pakistan because it was highly critical of the Pakistani military’s role in the former East Pakistan.

The magazine helped the group to forge a relationship with some Baloch nationalists who invited the group members to travel to Balochistan and help the nationalists set into motion some education related projects.

After the loss of East Pakistan in 1971, the populist PPP had formed a new elected government at the centre, whereas the leftist NAP was heading the provincial government in Balochistan.

In 1973, the PPP regime accused NAP of fostering a separatist movement in Balochistan and dismissed it.

In reaction, hordes of Baloch tribesmen picked up arms and triggered a full-fledged guerrilla war against the Pakistan Army.

About five members of the London Club decided to quit their studies in London, travel back to Pakistan and join the insurgency on the Baloch nationalists’ side.

They were all between the ages of 20 and 25, came from well-off families and none of them were Baloch.

Four were from the Punjab province and included Najam Sethi, Ahmed Rashid, and brothers Rashid and Asad Rehman. One was from a Pakistani Hindu family: Dalip Dass.

All wanted to use the Balochistan situation to ‘trigger a communist revolution in Pakistan.’

Dass was the son of a senior officer in the Pakistan Air Force. After his schooling in Pakistan, he had joined the Oxford University in the late 1960s where he became a committed Marxist.

Asad and Rashid Rehman were sons of Justice SA Rehman who had been a close colleague of the founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

Najam Sethi came from a well-to-do middle-class family in Lahore and so did Ahmad Rashid whose family hailed from Rawalpindi.

All five members had travelled to England to study in prestigious British universities.

Initially, they were energised by the left-wing student movements that erupted across the world (including Pakistan) in the late 1960s.

When they reached their respective universities in London, they got involved in the student movements there but kept an eye on the developments in Pakistan where a student movement had managed to force out the country’s first military dictator, Ayub Khan (in 1969).

The study group honed its knowledge of Marxism, but also began studying revolutionary guerrilla manuals authored by such communist revolutionaries as Che Guevara, Carlos Marighella and Frantz Fanon.

When a civil war between the Pakistan Army and Bengali nationalists began in 1971 in former East Pakistan, the group, that originally consisted of about 25 Pakistani students studying in England, began to publish a magazine called ‘Pakistan Zindabad’ that severely criticised the role of the Pakistani establishment in East Pakistan.

The magazine was smuggled into Pakistan and then distributed in the country by Pakistani left-wing student groups such as the National Students Federation (NSF) that had also led the movement against the Ayub regime.

One of the issues of the magazine fell into the hands of some veteran left-wing Baloch nationalist leaders in Balochistan.

One of them was Sher Muhammad Marri who at once sent Muhammad Babha to London to make contact with the publishers of the magazine.

Muhammad Babha whose family was settled in Karachi, met the members of the study circle in London and communicated Marri’s invitation to them to visit Balochistan.

Seven members of the circle agreed to travel to Balochistan. However, two backed out, leaving just five.

All five decided to travel back to Pakistan without telling their families who still thought they were studying in England.

The years 1971 and 1972 were spent learning the Baloch language and customs, and handling and usage of weapons - especially by Asad Rehman, Ahmad Rashid and Dalip Dass who would eventually join the Baloch resistance fighters in the mountains once the insurgency began in 1973.

Najam Sethi and Rashid Rehman stationed themselves in Karachi to secretly raise funds for the armed movement.

Each one of them believed that the government’s move against the NAP regime was akin to the establishment’s attitude towards the Bengalis of the former East Pakistan (that broke away in 1971 to become the independent Bengali state of Bangladesh).

The young men’s parents all thought their sons were in London, studying. It was only in 1974 when the government revealed their names that the parents came to know.

The three men in the mountains took active part in the conflict, facing an army that used heavy weaponry and helicopters that were supplied by the Shah of Iran and piloted by Iranian pilots.

All three had also changed their look to suit the attire and appearance of their Baloch comrades.

First to fall was the 23-year-old Dalip Daas. In 1974, while being driven in a jeep with a Baloch comrade and a sympathetic Kurd driver into the neighbouring Sindh province for a meeting with a Sindhi nationalist, the jeep was stopped at a military check-post on the Balochistan-Sindh border.

Daas and his Baloch comrade were asked to stay while the driver was allowed to go. Many believe the driver was an informant of the military.

Daas was taken in by the military and shifted to interrogation cells in Quetta and then the interior Sindh. There he was tortured and must have died because he was never seen again. He vanished.

For years friends and family of Daas have tried to find his body, but to no avail. He remains ‘missing.’

After Daas’ disappearance, Rashid Rehman who was operating with Najam Sethi in Karachi went deeper underground.

In 1976, the 28-year-old Sethi’s cover was blown and he was picked up by the military and thrown into solitary confinement.

More than 5,000 Baloch men and women lost their lives in the war that ended when the PPP regime was toppled in a reactionary military coup in 1977.

Asad and Rashid Rehman remained underground till 1978 before departing for Kabul and then to London.

Ahmed Rashid also escaped to London.

Asad returned to Pakistan in 1980 before going back, this time to escape the right-wing dictatorship of Ziaul Haq.

He again returned to the country and became a passionate human rights activist and continued speaking for the rights of the Baloch till his death in 2013.

After his release in 1978, Najam Sethi became a successful publisher and progressive journalist. Today he is also known as a celebrated political analyst and a popular TV personality.

Ahmad Rashid travelled to England, became a journalist and then a highly respected and best-selling political author and expert on the politics of Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Rashid Rehman returned to Pakistan from London and became a leading journalist and editor.

The conflict in Balochistan continues.

The views expressed by this blogger and in the following reader comments do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Dawn Media Group.